Abstract Data Types

In our discussion about ArrayLists and LinkedLists, we briefly discussed the properties of the List interface. These two List implementations were different in terms of utilizing computer memory and how worked “under-the-hood,” but from an outside program, they looked exactly the same. That is, the List interface has a certain number of special properties about it:

- It can multiple individual elements that are all of the same variable type.

- It can maintain the order of the elements.

- It can add, remove, access, and do many other things with the elements of the list.

- We can create lists, print lists, copy them, compare them, and a variety of other basic procedures.

The list can be thought of as having some set of fundamental properties for the user of the class. Any class that is able to implement all of these fundamental properties can therefore be considered a list.

A list is an example of an abstract data type (ADT), which is an abstract, mathematical classification for certain types of data types. ADTs are defined by the methods, fields, and properties that are available to the user when they use an implementation of the particular ADT. Each ADT is a general class of different ADT implementations. For example, a list is an ADT, and two different ADT implementations are ArrayList and LinkedLists.

In Java, abstract data types can be thought of as interfaces, which are a collection of abstract methods. An implementation of an interface then actually explicitly writes out what each of the abstract methods does. For example, the abstract methods that are compose the list interface can be found at this link here.

Let’s suppose that we wanted to write our implementation of list interface. Some of the methods in the Java list interface are a bit too advanced for us to actually implement, so let’s define our own list interface:

public interface MyListInterface<E> {

// Add an element to the beginning of the list.

public void add(E element);

// Get an element at a particular index.

// Return null if index is invalid.

public E get(int index);

// Change the element at the particular index.

// Return the previous element at that index.

// Return null and do nothing if index is invalid.

public E set(int index, E element);

// Remove the element at the particular index.

// Return the previous element at that index.

// Return null and do nothing if index is invalid.

public E remove(int index);

// Insert the element at the particular index.

public void insert(int index, E val);

// Return the index of the first index of an object

// in the list. Otherwise, if the object isn't found,

// return -1.

public int indexOf(E element);

// Return the number of elements in the list.

public int size();

// Convert the list into a String.

public String toString();

// Return whether the number of elements is zero in the list.

public boolean isEmpty();

}

This code is contained in its own standalone file MyListInterface.java. Any data structure that chooses to implement this MyListInterface interface is expected to implement at least all of these different methods.

You might also notice that the interface has a <E> appended to the end of its name. This because our list implementation will be a list of E type elements, where E is what we call a generic variable type. This means that we don’t really know what the variable type that our list will hold just yet, and want to make sure that our list can hold any type of variable. E could be ints, or chars, or some other type of variable.

To given an example of a data structure that implements this Java interface, let’s write a class called MyLinkedList, which will be a similar to a LinkedList that we’ve already seen previously.

public class MyLinkedList<E> implements MyListInterface<E> {

private static final int DEFAULT_CAPACITY = 10;

/* Constructor if initial capacity is given. */

public MyLinkedList(int initLength) {

// TODO

}

/* Constructor if initial capacity is not given. */

public MyLinkedList() {

this(DEFAULT_CAPACITY);

}

/* Add an element to the beginning of the list. */

public void add(E element) {

// TODO

return;

}

/*

* Get an element at a particular index. Return null if index

* is invalid.

*/

public E get(int index) {

// TODO

return null;

}

/*

* Change the element at the particular index. Return the previous

* element at that index. Return null and do nothing if index is

* invalid.

*/

public E set(int index, E element) {

// TODO

return null;

}

/*

* Remove the element at the particular index. Return the previous

* element at that index. Return null and do nothing if index is

* invalid.

*/

public E remove(int index) {

// TODO

return null;

}

/* Insert the new element at the particular index. */

public void insert(int index, E val) {

// TODO

return;

}

/*

* Return the index of the first index of an object in the list.

* Otherwise, if the object isn't found, return -1.

*/

public int indexOf(E element) {

// TODO

return -1;

}

/* Return the number of elements in the list. */

public int size() {

// TODO

return -1;

}

/* Convert the list into a String. */

public String toString() {

// TODO

return null;

}

/* Return whether the number of elements is zero in the list. */

public boolean isEmpty() {

// TODO

return false;

}

}

Here, we’ve already included the all of the method stubs, as specified by the MyListInterface, that we’ll have to write. Note that the class name at the top includes the modifying phrase implements MyListInterace<E>, which tells the class that it must implement all of the methods specified by the MyListInterface interface in order to be considered an implementation of this particular interface.

This is also the first time that we’ve seen a class that has two different constructors. You can create multiple constructors to handle what to do in different cases of arguments that are passed in. In this case above, we have specified constructors for two possible cases: (1) the caller gives us an initial capacity initLength for the list, or (2) the caller gives us no arguments. In the second case, we can see that all that will be done is that the constructor will simply call the other, first constructor, passing in the value of DEFAULT_CAPACITY for the initial capacity of the list. Here, for convenience, we have defined the DEFAULT_CAPACITY to have a value of 10. Often times, Java programmers like to only write one constructor method, and then have all the other constructor methods call that constructor method in some way. This is to avoid any code duplication (i.e. rewriting the same code over and over again), which is generally considered to be bad coding practice.

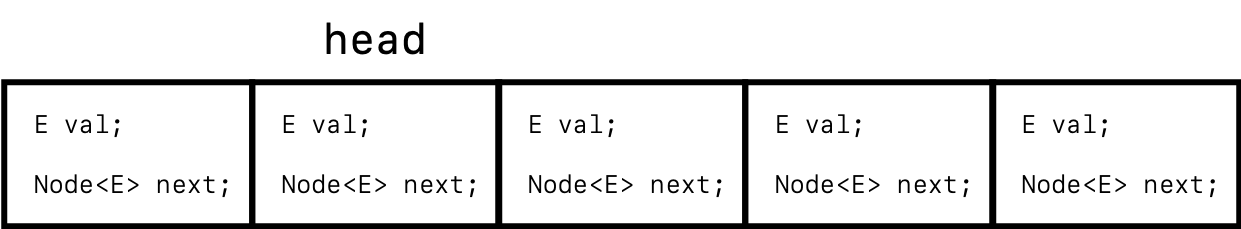

The next step is always to figure out exactly what our data structure will look like. Often times, in coding exercises like this, it is often useful to at least sketch out a rough schematic of what our data structure will look like. For example, our data structure MyLinkedList could look something like this:

As we can see, we’ll represent this data structure as an array of Node<E> objects. Each array element in this array is a Node<E> object (which we still need to define), which contains three fields: a field to store the value of the node, and one field to store a pointers to the next node in the list. Our MyLinkedList will also keep track of the head of the list so that we know what the first and last element of the list are, respectively. Because we don’t require our list elements to be contiguous, the head of the list can be anywhere in the array. If these terms sound unfamiliar, I encourage you to refresh your knowledge on LinkedLists here.

Now that we have a more concrete picture of what our data structure will look like, let’s actually implement it in code. The first thing that we need to do is write the Node<E> class. One possible implementation is shown here:

public class Node<E> {

public E val;

public Node<E> next;

/* Constructor if fields are explicitly given. */

public Node(E val, Node<E> next) {

this.val = val;

this.next = next;

}

/* Constructor if only value is given. */

public Node(E val) {

this(val, null);

}

/* Constructor if no arguments are given. */

public Node() {

this(null, null);

}

/* Returns the value stored by the node. */

public E getValue() {

return this.val;

}

/* Returns the next Node<E> of the list. */

public Node<E> getNext() {

return this.next;

}

/* Changes the value stored by the node. Returns the old value. */

public E setValue(E val) {

E oldValue = this.val;

this.val = val;

return oldValue;

}

/* Changes the pointer to the next node in the list. */

public void setNext(Node<E> next) {

this.next = next;

}

}

Now, we can start defining the appropriate fields and constructors for our MyLinkedList class. Here’s the relevant code snippet; try to read through it and see if you understand what is happening.

public class MyLinkedList<E> implements MyListInterface<E> {

private static final int DEFAULT_CAPACITY = 10;

// Keeps track of the starting Node<E> of the list.

private Node<E> head;

// Keeps track of the number of elements in the list.

private int size;

// Array to store the Node<E> objects that compose the list.

private Node<E>[] myArray;

/* Constructor if initial capacity is given. */

@SuppressWarnings("unchecked")

public MyLinkedList(int initLength) {

// Create the new array to store the Node<E> objects.

if (initLength > 0) {

this.myArray = (Node<E>[])(new Node[initLength]);

}

else {

this.myArray = (Node<E>[])(new Node[DEFAULT_CAPACITY]);

}

// No elements originally in the list.

this.size = 0;

// Since no element originally in the list, there is no head yet.

this.head = null;

}

/* Constructor if initial capacity is not given. */

public MyLinkedList() {

this(DEFAULT_CAPACITY);

}

.

.

.

}

Given that we’ve defined these fields and established what the basic data structure looks like now, some of the methods will be fairly easy to implement. For example, we can do size() and isEmpty() now:

public class MyLinkedList<E> implements MyListInterface<E> {

.

.

.

public int size() {

return this.size;

}

public boolean isEmpty() {

return (this.size < 1);

}

}

We will also discuss how to potentially implement the toString() method, since it is a good illustration of how to iterate over our linked list:

public class MyLinkedList<E> implements MyListInterface<E> {

.

.

.

/* Convert the list into a String. */

public String toString() {

StringBuilder string = new StringBuilder();

// Node<E> to keep track of the current node that we're on.

Node<E> current = this.head;

// Iterate over every node in the linked list in order.

while (current != null) {

string.append(current.getValue().toString() + " ");

current = current.getNext();

}

return string.toString();

}

}

The line instantiating the E[] array might look a bit funny, as we might expect the right hand side to look something like new E[this.size] instead of what it actually is. This has something to do with the fact that we’re creating an array of generic type variables, and the funky Java syntax that comes along with this. We’ll talk about what the above notation means later.

The while loop that is featured above is perhaps the most common method for iterating over a linked list data structure. Essentially, our algorithm has a local variable current keep track of which Node<E> we are currently at, and updates this pointer to the next Node<E> after ever iteration step. At the last node of the list, the “next” node of the last node is null, and so checking if current is null will tell us when to halt our iteration process.

The final method that we’ll provide an example for is the add() method. Recall that for adding an additional element, we need to make sure that the array that is storing the nodes of the list has enough entries. Otherwise, since we know that arrays are not able to dynamically change their size, we need to generate a new array of twice the current size, copy over all of the current nodes, and set our myArray field equal to the new array. We can do this in a private helper method. Implementing these methods and putting it all together, we have

public class MyLinkedList<E> implements MyListInterface<E> {

private static final int DEFAULT_CAPACITY = 10;

// Keeps track of the starting Node<E> of the list.

private Node<E> head;

// Keeps track of the number of elements in the list.

private int size;

// Array to store the Node<E> objects that compose the list.

private Node<E>[] myArray;

/* Constructor if initial capacity is given. */

@SuppressWarnings("unchecked")

public MyLinkedList(int initLength) {

// Create the new array to store the Node<E> objects.

if (initLength > 0) {

this.myArray = (Node<E>[])(new Node[initLength]);

}

else {

this.myArray = (Node<E>[])(new Node[DEFAULT_CAPACITY]);

}

// No elements originally in the list.

this.size = 0;

// Since no element originally in the list, there is no head yet.

this.head = null;

}

/* Constructor if initial capacity is not given. */

public MyLinkedList() {

this(DEFAULT_CAPACITY);

}

/*

* Helper function to resize our array when the maximum

* capacity is exceeded.

*/

@SuppressWarnings("unchecked")

private void ensureCapacity() {

if (this.size >= this.myArray.length) {

Node<E>[] newList = (Node<E>[])(new Node[2 *

this.myArray.length]);

for (int i = 0; i < this.myArray.length; i++) {

newList[i] = this.myArray[i];

}

this.myArray = newList;

}

}

/* Add an element to the beginning of the list. */

public void add(E element) {

// Create a new Node<E> to store the argument element.

Node<E> newElement = new Node<E>(element, this.head);

// Update the head of the list.

this.head = newElement;

// Update the size field.

this.size += 1;

// Use our helper method to ensure the array capacity.

this.ensureCapacity();

// Find a spot in the array to put our new list element.

for (int i = 0; i < this.myArray.length; i++) {

if (this.myArray[i] == null) {

this.myArray[i] = newElement;

return;

}

}

}

/*

* Get an element at a particular index. Return null if index

* is invalid.

*/

public E get(int index) {

// TODO

return null;

}

/*

* Change the element at the particular index. Return the previous

* element at that index. Return null and do nothing if index is

* invalid.

*/

public E set(int index, E element) {

// TODO

return null;

}

/*

* Remove the element at the particular index. Return the previous

* element at that index. Return null and do nothing if index is

* invalid.

*/

public E remove(int index) {

// TODO

return null;

}

/* Insert the new element at the particular index. */

public void insert(int index, E val) {

// TODO

return;

}

/*

* Return the index of the first index of an object in the list.

* Otherwise, if the object isn't found, return -1.

*/

public int indexOf(E element) {

// TODO

return -1;

}

/* Return the number of elements in the list. */

public int size() {

return this.size;

}

/* Convert the list into a String. */

public String toString() {

StringBuilder string = new StringBuilder();

// Node<E> to keep track of the current node that we're on.

Node<E> current = this.head;

// Iterate over every node in the linked list in order.

while (current != null) {

string.append(current.getValue().toString() + " ");

current = current.getNext();

}

return string.toString();

}

/* Return whether the number of elements is zero in the list. */

public boolean isEmpty() {

return (this.size < 1);

}

}

There are still a number of methods to still write: namely, the set(), remove(), insert(), and indexOf() methods. In one of the exercises below, you will be asked to write the implementations for each of these five methods.

Recap

To review, we learned that abstract data types are these generic “pictures” of what a particular set of data structure implementations might look like. More specifically, they represent a generic set of function prototypes that specify the minimum requirements for a particular Java class to be considered an implementation of an ADT/interface. To specify that a class MyClass implements an interface MyInterface, our code would look something like

public class MyClass implements MyInterface {

// Implement the methods specified by MyInterface here

}

In the sections above, we showed a (partial) example of implementing a linked list that implemented the MyList interface we defined above.

Exercises

Problem 1

From the MyLinkedList example above, we still need to implement the set(), remove(), insert(), and indexOf() methods. Implement them now.

Problem 2

Write your own test code to ensure that all of your MyLinkedList methods are running properly. Be sure to also include “edge cases,” such as adding the very first element of the list and removing the last element of the list.

Problem 3

Write an MyArrayList implementation of the MyListInterface from above. It should manage the list elements similarly to how the Java ArrayList functions. To review the Java ArrayList structure, take a look at this page.