Tree Search Algorithms (BFS and DFS)

Learning Objectives: By the end of this learning module, you should understand...

- the basics of a graph and how to identify and represent trees in Java.

- the idea and possible implementations behind breadth first search and depth first search tree-searching algorithms.

- the advantages of having a

verboseflag when writing programs.

Today, we will be discussing efficient algorithms for us to search and traverse through trees. To start off, let’s first figure out exactly what a “tree” is.

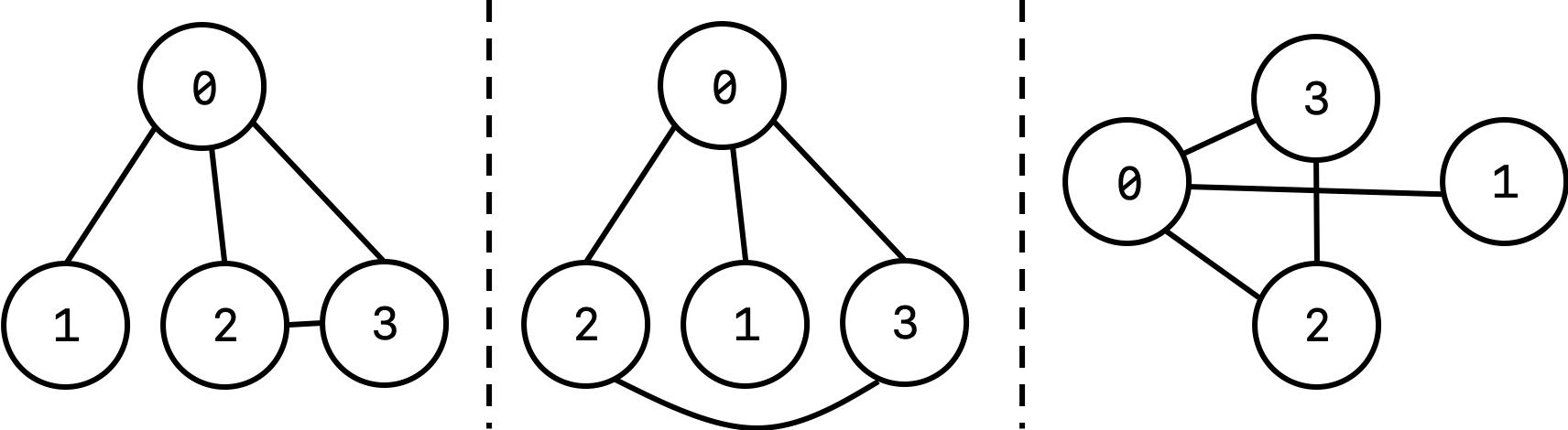

Graphs

The first thing that we’ll talk about today is something called a graph. A graph is an abstract mathematical object that is defined to consist of a set of vertices (nodes) and a set of edges that connect different vertices. Each of the vertices might have some value associated with them. As an example, we can think of a map as a graph, where cities are the vertices and the roads connecting different cites are the edges. However, unlike the relative locations of cities on maps, vertices and edges can be drawn however you like spatially. For example, the following three graphs are all equivalent:

Trees

A tree is a special type of graph in which any two vertices are connected by exactly one path. Equivalently, a tree is an connected, acyclic undirected graph. This is a very complicated definition so let’s break down what all of these words and descriptions mean:

- Connected: A connected graph is a graph in which there exists a path that goes from any vertex to any other vertex. Going back to our road analogy, this means that there is a set of roads between any two cities. For example, we know that there exists a set of roads that connects LA to New York. You might have to first drive through Chicago, and then Philly, and maybe some other cities/vertices, but ultimatley you can drive from LA to New York. A connected graph ensures that you can always “drive” from any vertex to any other vertex using the edges in the graph.

- Acyclic: An acyclic graph means that the graph doesn’t have any cycles. This means that there only exists one path (or one set of “roads”) connecting any two vertices. For example, if you want to drive from LA to New York, an acyclic graph means, that there exists exactly one set of roads that connects LA to New York. You might have to drive from LA to Chicago to Philly to New York, and this will be the only path from LA to New York. There’s no such thing as a “different” return trip: to get back to LA, you have to drive from New York to Philly to Chicago to LA because there are no other connecting paths.

- Undirected: All of the edges in the graph must be undirected. In other words, this means that between any two cities/vertices connected by an edge, you can “drive” in either direction: none of the roads are “one-way”.

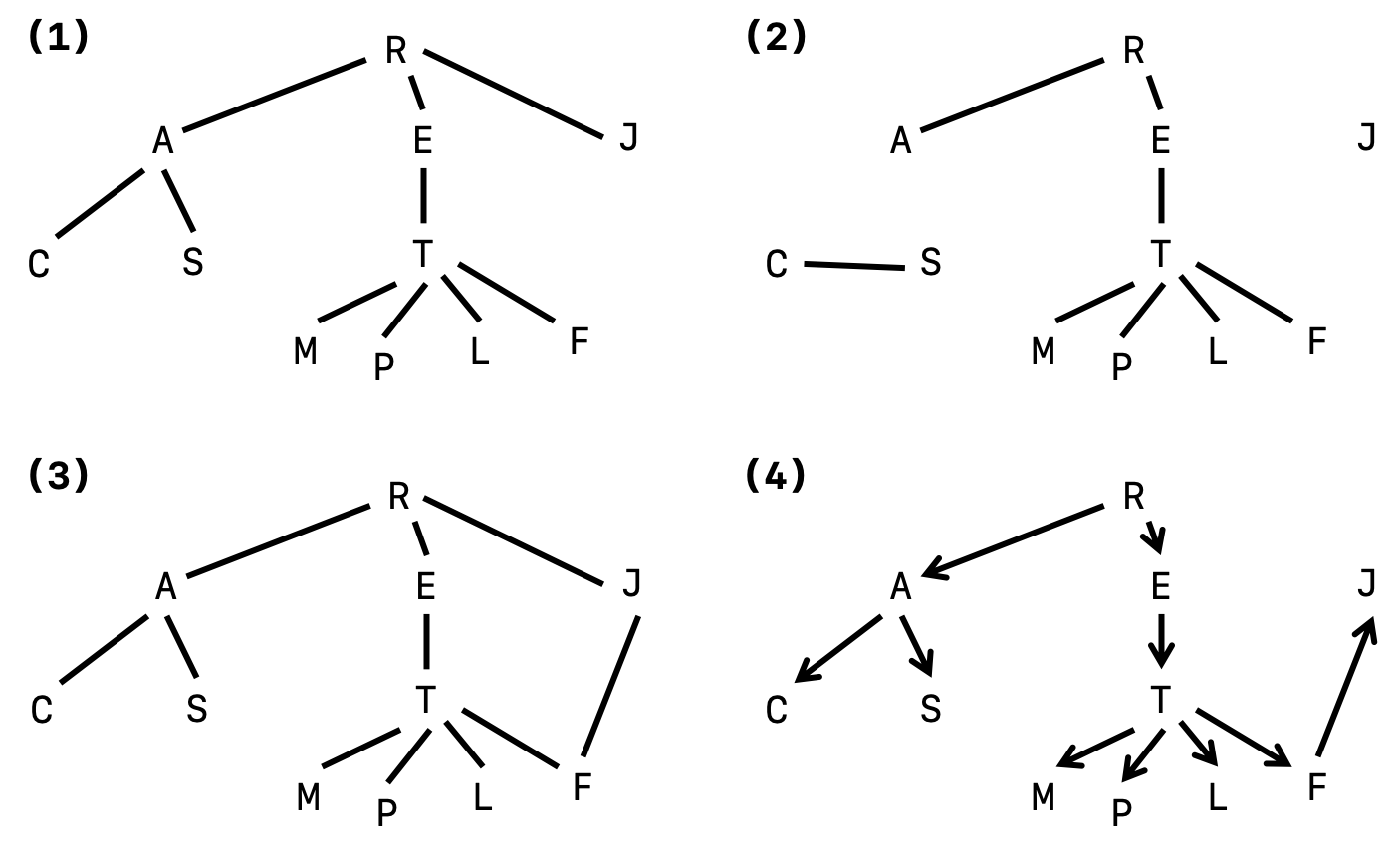

Example 1: Which of the following set of graphs are trees, and which are not? Explain your reasoning.

Hover here to see the solution.

(2) is not a tree because vertices J, C, and S are not connected to the rest of the "main graph," and so this is not a connected graph. (3) is also not a tree because there exists a cycle RETFJ, and we know that trees should be acyclic. (4) is not a tree because the arrows suggest that the graph is a directed graph where the edges can only travel in one particular direction. Therefore, (1) is the only tree out of the four possible answers.

Let’s focus on Graph (1) that’s shown in the exercise above. Vertex R is referred to as the root of the tree because it is the source that all other vertices are connected to. The minimum number of edges you have to traverse to get to the root from any particular vertex is called the depth of that vertex. For example, the root R has depth 0, vertices A, E, and J have depth 1, and vertices C, S, and T have depth 2.

Consider a vertex V with depth $i$ and a vertex V’ directly connected to it with depth $i+1$. We call vertex V the parent of the vertex V’, and vertex V’ the child of the vertex V. For example, vertices C and S are children of vertex A, and vertex A, E, and J are children of vertex R. A vertex with no children is referred to as a leaf. For example, vertices C, S, M, P, L, and F are all referred to as the leaves of tree (1).

Tree Search Algorithms

Now that we have an idea what exactly a tree is, we can start talking about tree search algorithms. These algorithms are basically different ways to visit all vertices and edges of a particular tree. However, the way in which they accomplish this is verty different, and so for that reason, the two algorithms that we’ll be looking at today serve very different purposes.

Breadth First Search (BFS)

BFS is one type of tree-searching algorithm. The idea is that this algorithm explores nodes in order of their depth. We start out at the root vertex, then explore all of the vertices with depth 1 first, and then vertices with depth 2, and so on and so forth. In other words, there is an order in which the traversal process is performed. Here’s an animation of this process:

How is this depth-based traversal algorithm achieved? The idea is that use a queue data structure to keep track of which vertex to visit next. The algorithm looks something like this:

bfs_algorithm {

1. create a queue of vertices;

2. add root to the queue to start;

while queue is not empty {

3. get vertex from front of queue;

4. make sure this vertex has not been visited before;

5. look at it's value and do things as appropriate;

6. add the children of the vertex to the back of the queue;

7. mark the vertex as visited;

}

}

Conceptually, nodes of smaller depth that are closer to the root will be added first to the queue, and so because the queue is a FIFO data structure, these nodes of smaller depth will be visited before nodes that are further away from the root. In this way, you can see that the the BFS traversal algorithm expands its search radius in breadth over time, as the radius of searching away from the root gradually increases over time. This is a characteristic feature of the BFS algorithm.

In general, BFS is good for finding the shortest path between the root and any other vertex in the tree. This is because BFS will reach any particular vertex with the minimum number of edges from the root source, as we noted that nodes of smaller depth will be visited first before nodes of greater depth. However, BFS is typically a slower algorithm when compared to DFS, which is another tree searching algorithm that we’ll look at next.

Depth First Search (DFS)

DFS is the other, main type of tree-searching algorithm. The idea is that this algorithm explores any particular path all the way “down” to the leaves of the path, and then slowly traverses back up the tree. We start out at the root vertex and then pick any path connecting the root to a leaf, exploring all of the intermediate vertices in the process. Here’s an animation of this process:

Image Credits: Zack Banack

Image Credits: Zack Banack

How is this depth-based traversal algorithm achieved? The idea is that use a stack data structure to keep track of which vertex to visit next. The algorithm looks something like this:

dfs_algorithm {

1. create a stack of vertices;

2. add root to the stack to start;

while stack is not empty {

3. pop vertex from top of stack;

4. make sure this vertex has not been visited before;

5. look at it's value and do things as appropriate;

6. push the children of the vertex to the top of the stack;

7. mark the vertex as visited;

}

}

As we can see, the algorithm is really similar to the BFS algorithm, which the exception that we use a stack to decide which vertex to visit next instead of queue. This rather subtle change has a really big difference on how we traverse through the tree: because a stack if a LIFO data structure, the children of nodes will be visited before other parent nodes at the same depth. This allows the algorithm to explore paths all the way down to the leaves, which is why the algorithm is called depth first search.

In general, DFS is usually a faster algorithm than DFS, and while it doesn’t find the shortest, optimal path between the root and a vertex like BFS does, it’s able to find a path rather quickly. In particular, DFS is usually pretty suitable for exploring trees that represent a particular game or puzzle: we make a decision, and then explore all paths through this decision. This is in contrast to BFS which would be fairly ill-suited for this task.

Example 2: Consider the following two real-life scenarios. Which of these would the solution algorithm best utilize DFS, and which would best utilize BFS? Explain your reasoning.

- Determine what the best move is to play in a chess game.

- Determine the shortest path between two points on a grid.

Hover here to see the solution.

Scenario (1) would use a DFS algorithm. We can model each possible state of a chess board as a vertex in a graph, and each edge would be a possible move to get from one chess board state to another. In this case, the root of this tree is the current state of the chess board, and we want to explore any path all the way down to its "maximum depth" in order to determine whether the final state of the board is winning for a player. This is accomoplished through DFS.

Scenario (2) would use a BFS algorithm. This is because the scenario is specifically asking us to determine the shortest, optimal path between two points. In this case, we can model each of the points on the grid as vertices in a tree, with edges drawn between adjacent points, and the root being the point that we're currently at. In this model, the length of the shortest path would simply be the depth of the final point compared to the current point we are located at.

This concludes our discussion on the BFS and DFS algorithms. In the set of problems below, you will implement these algorithms in Java using the algorithmic pseudo-code that we’ve described above.

verboseFlags

We’re also going to briefly talk about a somewhat unrelated topic: verbose flags. This is a general, common programming technique that you might see when looking at other people’s code, and even something that you should consider when writing some of your own programs!

A verbose flag is essentially a boolean that, if set equal to true, turns on the ability to provide additional details as to what the computer is doing, what is the current state of the program and some of the important local variables, and so on. This often makes it easier for you (and the user) to debug code and understand what the code is doing.

Example

Suppose that we want to sum up all of the numbers from 1 to n, where n is some positive integer. Our code might look something like

public static void main(String args) {

int sum = 0;

int n = 10;

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

sum += (i + 1);

}

System.out.println(sum);

}

Suppose that we want to implement a verbose flag. What information might be important for the user to know or understand how the program works? We might want to keep track of the current value of sum, and maybe also the current value of i. So, we can change our implementation to look something like:

public static void main(String args) {

static final boolean VERBOSE = true;

int sum = 0;

int n = 10;

if (VERBOSE) {

System.out.print("The value of n is ");

System.out.println(n);

System.out.println();

}

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

if (VERBOSE) {

System.out.print("Current value of i: ");

System.out.println(i);

System.out.print("Current value of sum: ");

System.out.println(sum);

System.out.println();

}

sum += (i + 1);

}

System.out.println(sum);

}

In this way, if the user sets VERBOSE = true, then helpful information will be printed out to the terminal for the user to better understand (or debug) the program. If the user doesn’t want to see that information, then they can just change VERBOSE = false to turn off the verbose flag. As we can see, the verbose flag option is a powerful way for us to provide useful information about the program to the user.

In the following exercise, you will write a sample implementation of BFS and DFS algorithms that also incorporates a verbose flag.

Your Turn

Now that you understand the idea behand our two tree search algorithms, it’s your turn to implement them! Navigate to the repl linked here, which is also shown below, and follow the following steps.

Problem 1

Read through the Main.java source code and make sure that you understand how the code functions. In the beginning of the driver program, there are a set of nodes and edges created to represent the tree. Draw out the tree and what it looks like (it should be the same as the example tree we looked at above).

Problem 2

Implement the DFS algorithm that we’ve described above. Once you have completed that, compare your implementation with the solution implementation shown in sol/DFSIterativeSol.java in the same repl.

Problem 3

Implement the BFS algorithm that we’ve described above. Once you have completed that, compare your implementation with the solution implementation shown in sol/BFSIterativeSol.java in the same repl.

Problem 4

Run your program to test both your BFS Implementation and DFS Implementation through appropriately modifying the last couple of lines of Main.java’s driver program. Turn the verbose flag on to observe the behavior of the algorithms. Do they behave as expected? As you can hopefully see, having a verbose flag option makes debugging code and understanding algorithms a lot easier!

Problem 5

The implementations of BFS and DFS that we learned about today are what we call iterative algorithms. This means that they use iteration through either for or while loops to traverse through all of the notes in the tree. How could you potentially modify your implementations so that they are recursive algorithms, which substitute any looping with recursive function calls? To see an example of BFS implemented recursively, visit this link. To see an example of DFS implemented recursively, visit this link.