Newton’s Laws and Kinematic Equations

Important Quantities in Physics

Physics is the practice of describing physical quantities using the formalism of mathematics. To illustrate the usage of physics let’s consider a car that is driving down a straight road. What are the important quantities for us to think about?

One quantity is position $\vec{x}$, also referred to as displacement from our origin of travel (it could be our home, for instance). How far are we out from the origin? Another is velocity $\vec{v}$: how fast are we driving and in which direction are we driving? Finally, we also care about the acceleration. Are we stepping in the gas pedal like a race car driver or as a very safe and cautious driver? In this case, the relevant quantity is acceleration $\vec{a}$. We are similar with what these quantities are in real life, but how to we represent them mathematically? We can relate the quantities in the following way:

\[\vec{v}=\frac{d\vec{x}}{dt}, \quad \vec{a}=\frac{d\vec{v}}{dt}\]In other words, velocity is the time derivative of position (ie change in position divided by the change in time) and acceleration is the time derivative of velocity (ie change in velocity divided by the change in time).

There is also another important quantity in physics called force. The force $\vec{F}$ on a particular object with mass $m$ is defined by the following definition:

\[\vec{F}=m\vec{a}\]Newton’s Laws

Newton’s Laws describe the classical motion of any object. They are:

- If the net force on an object is zero, the object will remain at constant velocity. This means things that are at rest, stay at rest, and things that are moving continue to move at constant velocity.

- The sum of all the forces on an object, $\sum \vec{F}$, is called the net force $\vec{F}_{\text{net}}$, and is given by \(\sum \vec{F}=\vec{F}_{\text{net}}=m\vec{a}\).

- For two objects $1$ and $2$ in contact, \(\vec{F}_{1\rightarrow 2}=-\vec{F}_{2\rightarrow 1}\).

A force $\vec{F}$ is a vector quantity and defined to be the product of an object’s mass $m$ and acceleration $\vec{a}$. The unit of force is the Newton $\text{N}=\text{kg}\cdot\text{m}\cdot\text{sec}^{-2}$.

Kinematic Equations

Kinematic equations apply for any motion in a given dimension assuming constant acceleration. They are a set of four equations that we can derive simply from the fact that acceleration is a constant.

First, we know that acceleration $a=\frac{dv}{dt}$, where $a$ is the magnitude of acceleration and $v$ is the magnitude of the velocity (ie speed). Therefore, $dv=a\text{ }dt$. Integrating both sides from some initial time point $t_i$ to some final time point $t_f$ gives

\[\int_{v_i}^{v_f}dv=\int_{t_i}^{t_f}a\text{ }dt=a\int_{t_i}^{t_f}dt\]Here, we are able to take the acceleration magnitude $a$ out of the time integral on the right hand side because it is assumed to be a constant. Evaluating the integral on both sides, we have

\[v_f-v_i=a(t_f-t_i)\longrightarrow v_f=v_i+a(t_f-t_i)\]If we fix $v_i=v_0$ to be some constant, and $v_f$ to be variable and a function of $t$, then we can see that

\[\boxed{v=v_0+at}\]This is our first kinematic equation. Similarly, since $v=\frac{dx}{dt}$, where $x$ is the position of the object, then we have

\[x=\int dt\text{ }v=\int dt(v_0+at)=v_0t+\frac{1}{2}at^2+C\]To evaluate the integral on the right hand side, we used the fact that $v_0$ and $a$ are constants. $C$ can be set by using the initial conditions that $x=x_0$ at time $t=0$, and so $C=x_0$. Therefore, we have

\[\boxed{x=x_0+v_0t+\frac{1}{2}at^2}\]Note that we can rewrite this equation as

\[x=x_0+\frac{1}{2}v_0t+\frac{1}{2}(v_0+at)t\]Using the fact that $v=v_0+at$, we have

\[\boxed{x=x_0+\frac{1}{2}v_0t+\frac{1}{2}vt=\frac{v+v_0}{2}t}\]Rearranging this equation gives \(v+v_0=\frac{2(x-x_0)}{t}\). Furthermore, since $v=v_0+at$ from above, this means that \(v-v_0=at\). Multiplying these two equations together gives

\[(v+v_0)(v-v_0)=v^2-v_0^2=\frac{2(x-x_0)}{t}at=2a(x-x_0)\]Simplifying gives

\[\boxed{v^2=v_0^2+2a(x-x_0)}\]Collectively, these four equations can be summarized as the following:

The kinematic equations (assuming constant acceleration) are

- $x=x_0+v_0t+\frac{1}{2}at^2$

- $v=v_0+at$

- $x=x_0+\frac{v+v_0}{2}t$

- $v^2=v_0^2+2a(x-x_0)$

For projectile trajectory problems involving gravity, $a=g\approx 10\text{ m}\cdot\text{sec}^{-2}$. Remember that gravity always acts in the $-\hat{y}$ direction!

Example Problems

In this section, we will discuss how to to apply this theory in a couple of example problems.

Example 1

A race car starting from rest accelerates at a constant rate of $5\text{ m}\cdot\text{sec}^{-2}$.

- What is the velocity of the car after it has traveled $100\text{ m}$?

- How much time has elapsed?

We are given the the race car has a constant acceleration of $a=5\text{ m}\cdot\text{sec}^{-2}$. Therefore, we can apply the kinematic equations to this problem. We’re given $\Delta x=100\text{ m}$ and $v_0=0\text{ m}\cdot\text{sec}^{-1}$ (since the car starts at rest). Therefore, we can apply the following equation:

\[v^2=v_0^2+2a(\Delta x)=\left(0\text{ m}\cdot\text{sec}^{-1}\right)^2+2\left(5\text{ m}\cdot\text{sec}^{-2}\right)\left(100\text{ m}\right)\]Simplifying gives

$$v^2=1000\text{ m}^2\cdot\text{sec}^{-2}\longrightarrow v=10\sqrt{10}\text{ m}\cdot\text{sec}^{-1}$$

To determine the amount of time $t$ elapsed, we can use the fact that we solved for the final velocity $v$:

$$v=v_0+at\longrightarrow t=\frac{v-v_0}{a}=\frac{10\sqrt{10}\text{ m}\cdot\text{sec}^{-1}}{5\text{ m}\cdot\text{sec}^{-2}}=2\sqrt{10}\text{ sec}$$

Example 2

Suppose a ball with mass $m$ is thrown upwards from an initial height $y_0$ and initial velocity $v_0$.

- At what time $t_{\text{max}}$ does the ball reach its maximum height?

- What is the maximum height reached $y_{\text{max}}$?

This is an example where gravity is the only force acting on the ball, and so the acceleration of the ball is $a=-g\hat{y}$. We are given that the ball has an initial position $y_0$ and initial velocity $v_0$. To determine the time $t_{\text{max}}$, we will use the fact that when the ball reaches its maximum height, it instantaneously has zero velocity. Therefore,

\[v=v_0+at_{\text{max}}\longrightarrow 0\text{ m}\cdot\text{sec}^{-1}=v_0-gt_{\text{max}}\longrightarrow gt_{\text{max}}=v_0\]Solving for $t_{\text{max}}$ gives

$$t_{\text{max}}=\frac{v_0}{g}$$

To determine the maximum height, we use another kinematic equation and our result for $t-{\text{max}}$:

\[y_{\text{max}}=y_0+v_0t_{\text{max}}-\frac{1}{2}gt_{\text{max}}^2=y_0+\frac{v_0^2}{g}-\frac{g}{2}\frac{v_0^2}{g^2}\]Simplifying this equation gives

$$y_{\text{max}}=y_0+\frac{v_0^2}{2g}$$

Work and Energy

Work $W$ is defined by

\[W=\int_{\vec{x}_i}^{\vec{x}_f}d\vec{x}\cdot\vec{F}(\vec{x}) \text{ or } W=\int_{x_i}^{x_f}dx\text{ }F(x)\]The first definition above is in 2- or 3- dimensions and is the more general case (we will talk about how to actually evaluate such an integral later). You will most likely find the second definition of work given more useful. Work is the space-integral of force. Energy $U$ is defined by

\[-\vec{\nabla}U=\vec{F}(\vec{x}) \text{ or } -\frac{dU}{dx}=F(x)\]Again, the notation in the first definition is probably unfamiliar, so just ignore it for now. If you look at the definitions of work and energy, you can see that $W=-F$. We say that work $W$ is path-independent if $F$ is a conservative force (which is most forces). Note that in order to do work on an object, the object must move (in other words, holding a brick in the air but not moving it does no work!). The unit of force is the Joule $\text{J}=\text{kg}\cdot\text{m}^2\cdot\text{sec}^{-2}$.

Exercises

Problem 1

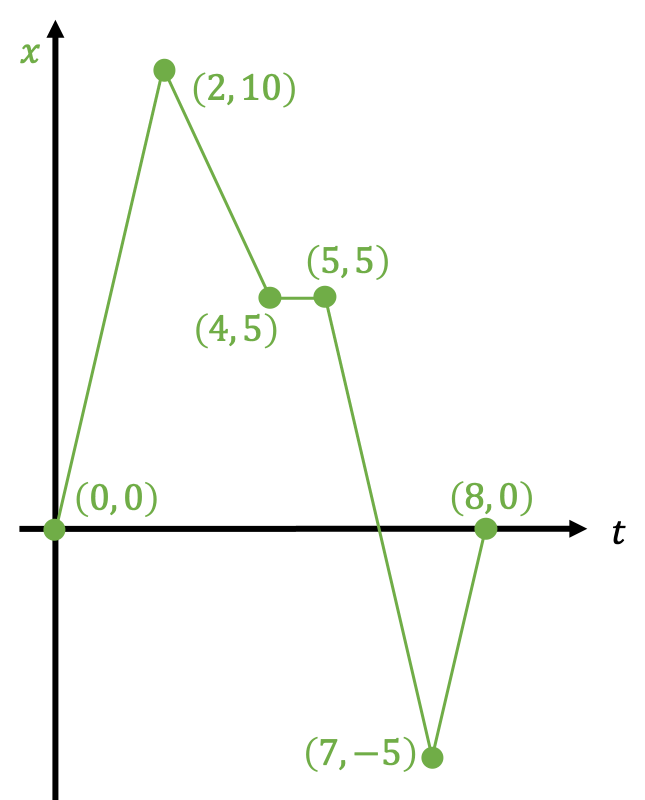

A graph of position $x$ versus time for a certain particle moving along the $x$-axis is shown here in green:

Find the average velocity in the time intervals between...

- 0 to 2 sec

- 0 to 4 sec

- 2 to 4 sec

- 4 to 7 sec

- 0 to 8 sec

Problem 2

An electron is traveling in the $+\hat{x}$ direction at an initially constant speed of $v=2.10\times 10^7\text{ m}\cdot\text{sec}^{-1}$. The electron enters an electric field at time $t=0$ that deflects the electron by giving it a constant acceleration of $5.30\times 10^{15}\text{ m}\cdot\text{sec}^{-2}$ in the $+\hat{y}$ direction.

- How long does it take for the electron to cover a horizontal distance of $6.2\times10^{-2}\text{ m}$?

- What is the vertical displacement of the electron during this time?

Problem 3

Consider a one-dimensional system with a position-dependent force $F(x)$ acting on a particle over the entirety of the real number line.

- Take \(F(x)=e^{-\vert x\vert}\). What is the work required to ‘push’ the particle from \(x=-1\) to \(x=1\)?

- Take \(F(x)=e^{-\vert x\vert}\). What is the work required to ‘push’ the particle from \(x=-\infty\) to \(x=\infty\)?

- Take $F(x)=xe^{-x}$. What is the total energy stored in the system between $x=0$ and $x=\infty$?

- It is not possible to calculate the total energy of the system described in Part (3) above from $x=-\infty$ to $x=\infty$. Why? Hint: What is the value of $F(x)$ at $x=-\infty$?