Spring and Kinetic Energy

We’ve spent the last two sessions introducing the concept of simple harmonic motion, and considering the cases of both oscillating masses with and without friction. Today, we’ll be looking more closely at how we can describe the energy of oscillating systems.

Review of Energy

Recall that we previously defined the energy $U$ of a system using the following equation:

\[F=-\frac{dU}{dx}\]Here, $F$ refers to the net force in the system while $U$ is the total energy of the system. Note that we can rewrite this equation in the following way:

\[dU=-dx\text{ }F\longrightarrow U=-\int dx\text{ }F+U_0\]where $U_0$ is simply constant that we call the zero-point energy. $U_0$ can be thought of as defining the relative energy scale for the system. For our purposes, to keep things simple, we’ll choose $U_0=0$ unless otherwise noted.

Energy Stored in a Spring

Let’s assume that the only force acting on a mass is the spring force, which we determined previously can be written as $F_{\text{spring}}=-kx$. Using the formula for the energy of a system that we found above, we have

\[U_{\text{spring}}=-\int dx\text{ }F_{\text{spring}}=-\int dx(-kx)=k\int dx\text{ }x\longrightarrow U_{\text{spring}}=\frac{k}{2}x^2\]This gives us a formula to describe the contribution to the total energy of a system that is stored in a spring.

Kinetic Energy of an Object

We should also introduce the idea of kinetic energy, which is defined to be energy that an object has simply due to the fact that it is in motion. Again, we can find an expression for the kinetic energy of an object by using the relation that $U=-\int dx\text{ }F$ that we proved above. Note that if work is done on a mass to accelerate it and make it start moving, then force exerted by the system is actually negative, meaning that $F_{\text{kinetic}}=-ma$ in this case, where $m$ is the mass of the object and $a$ is the magnitude of the acceleration of the object. Therefore, we find that

\[U_{\text{kinetic}}=-\int dx\text{ }F_{\text{kinetic}}=-\int dx(-ma)=m\int dx\frac{dv}{dt}\]We made the last simplification step by using the fact that acceleration is defined to be the time derivative of the velocity of the object. If we rearrange the differential elements on the right hand side, we find

\[U_{\text{kinetic}}=m\int dx\frac{dv}{dt}=m\int dv\frac{dx}{dt}=m\int dv\text{ }v\]Here, we have used the fact that the time derivative of the a mass’s position is simply defined to be the velocity of the mass. Carrying out the integration, we find that

\[U_{\text{kinetic}}=\frac{1}{2}mv^2+U_0=\frac{1}{2}mv^2\]Again, we set the constant of integration $U_0=0$ simply for convenience, but really, we could define it to be whatever we want. Therefore, our collective work from the above two sections has given us the following energy relations:

\[U_{\text{kinetic}}=\frac{1}{2}mv^2, \quad U_{\text{spring}}=\frac{1}{2}kx^2\]Total Energy of an Oscillating System

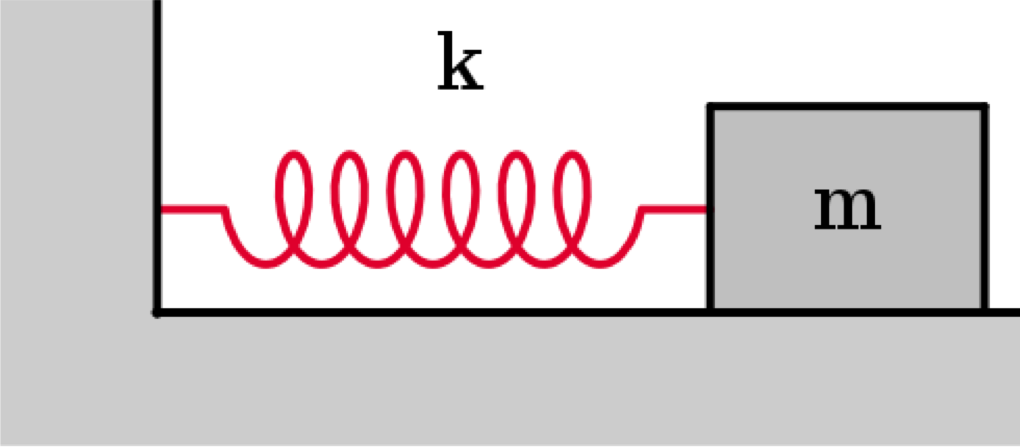

Let’s consider our standard setup of a spring with spring constant $k$ connected to mass $m$ resting on some surface.

Image obtained from Wikimedia Commons.

From this system, it’s clear that there are only two different sources at play (at least in the $\hat{x}$ direction): the spring energy stored in the spring, and the kinetic energy due to the motion of the mass $m$. If we sum the energy contributions of both of these sources, then we get the total energy $U$:

\[U=U_{\text{spring}}+U_{\text{kinetic}}=\frac{1}{2}kx^2+\frac{1}{2}mv^2\]No Friction

From our discussion of simple harmonic oscillation without the presence of any friction, we determined that the general solution to the SHODE for this setup is given by

\[x(t)=A\sin(\omega t)+B\cos(\omega t) \longrightarrow v(t)=A\omega \cos(\omega t)-B\omega \sin(\omega t)\]for some constants $A, B$, and with $\omega=\sqrt{k/m}$. If we plug these expressions into our equation for $U$ from above, we find

\[U=\frac{1}{2}k(A\sin(\omega t)+B\cos(\omega t))^2+\frac{1}{2}m\left(A\sqrt{\frac{k}{m}}\cos(\omega t)-B\sqrt{\frac{k}{m}}\sin(\omega t)\right)^2\]Using the identity $\sin^2\theta+\cos^2\theta=1$, we can simplify this equation algebraically to find

\[U=\frac{1}{2}k(A^2+B^2)\]Notice that since $k, A, B$ are all simply constants, the total energy of the system is constant with respect to time! This tells us that energy is never being gained or losses by the system if it’s left unperturbed: energy is simply being transformed between kinetic and spring energy over time.

With Friction

From our discussion of damped harmonic oscillation, we learned how the solutions behaved either with critical damping, underdamping, and overdamping. For sake of argument, let’s consider the critical damping solution for our discussion today:

\[x(t)=Ae^{-\gamma t/2m}+Bte^{-\gamma t/2m}, \quad v(t)=\frac{-(A+Bt)\gamma}{2m}e^{-\gamma t/2m}+Be^{-\gamma t/2m}\]We can plug this into our expression for the total energy of the system $U=\frac{1}{2}kx^2+\frac{1}{2}mv^2$:

\[U=\frac{1}{2}k(Ae^{-\gamma t/2m}+Bte^{-\gamma t/2m})^2+\frac{1}{2}m\left(\frac{-(A+Bt)\gamma}{2m}e^{-\gamma t/2m}+Be^{-\gamma t/2m}\right)^2\]We will leave out any discussions of the complicated algebraic simplification and instead simply give the result:

\[U=e^{-\gamma t/m}\left[\frac{B^2m}{2}+(A+Bt)\left(k(A+Bt)-\frac{2Bkm}{\gamma}\right)\right]\]The energy is equal to some sort of constant that depends on the parameters of the problem, multiplied by an exponential decay term equal to $e^{-\gamma t/m}$. This tells us that over time, the energy of the critically damped harmonic oscillator decreases exponentially. Intuitively, this should make sense. As we saw when originally learning about damped harmonic oscillation, we know that gradually, the block is moving and then ultimately approaches its rest equilibrium length when it ultimately stops. This perfectly describes the dissipation of energy over time, and so in this case, energy is not conserved.

Conservation of Energy

The comparison between the no-friction and with-friction introduces a very important concept: conservation of energy. As we saw above, when no friction is present, then the energy of the system is conserved, but once friction is introduced into a system, then the energy of the system is no longer conserved. The idea of conservation of energy will continue to come up in the future. In general, as long as all of the forces present in a system are conservative, then energy will be conserved. If there is a single non-conservative force (for example, friction), then energy will not be conserved.

Exercises

Problem 1

This problem is adapted from Khan Academy.

Dana pulls a spring with a spring constant $k=300\frac{N}{m}$, stretching it from its rest length 0.40 m to 0.50 m. What is the elastic potential energy $U_{\text{spring}}$ stored in the spring?

Problem 2

This problem is adapted from Serway Physics, 9th Edition.

If an object of mass $m$ attached to a massless spring is replaced by one of mass $9m$, then the frequency $\omega$ of the vibrating system changes by what multiplicative factor?

Problem 3

This problem is adapted from Serway Physics, 9th Edition.

A block of mass $m=2.00$ kg is attached to a spring with $k=5.00\times10^2$ N/m that lies on a horizontal frictional surface similar to the one shown above. The block is pulled to a displacement of $x_i=5.00$ cm to the right of the equilibrium position and then released from rest. Find…

- The work required to stretch the spring.

- The speed of the block as it passes through the equilibrium point.