Bitwise Operations

Bitwise operations are an important and efficient set of instructions to perform on individual bits in C. In this module, we will discuss the different types of bitwise operations and also their utility in different situations.

Introduction

A bitwise operation is an operation that takes in two bits and spits out another bit. (In some special cases, we may require only one bit, as with the NOT operator.) To perform a bitwise operation on an entire string of bits, we go through the string bit by bit and perform the required operation, concatenating the resulting output bits together to give the final result.

There are six different basic bitwise operations that we will discuss today. While there are more complicated ones out there, these are the fundamentals.

| Symbol | Operation |

|---|---|

& |

AND |

| |

OR |

^ |

XOR |

~ |

NOT |

<< |

left shift |

>> |

right shift |

To best understand the meaning of each of these operations, we will use the convention that the 0 bit stands for false and the 1 bit stands for true.

ANDOperator

The AND operator returns whether or not two statements are both true. That is, it returns true if both statement a and statement b are true, and returns false in any other case. Our “truth table” to represent the AND operator is

a |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

b |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

a & b |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

OROperator

The OR operator returns whether it is true that either one statement or the other (or both) is true. That is, it returns true if either statement a and statement b is true (or both), and returns false in any other case. Our truth table to represent the OR operator is

a |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

b |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

a & b |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

XOROperator

The XOR operator returns whether it is true that either one statement or the other (but not both!) is true. That is, it returns true if either statement a and statement b is true, and returns false in any other case. Our truth table to represent the XOR operator is

a |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

b |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

a & b |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

XOR stands for eXclusive OR. The “exclusive” part tells us that both bits cannot be true at the same time. Otherwise, the operation will return false. (In a similar fashion, the OR operation is sometimes also referred to as inclusive OR, although this convention is not as common.)

NOTOperator

The NOT operator is a bit (haha, unintended pun ![]() ) special in that it only operates on one bit, not on two bits (in contrast to the three operations from above). It basically returns the opposite of the input bit. If the input bit is

) special in that it only operates on one bit, not on two bits (in contrast to the three operations from above). It basically returns the opposite of the input bit. If the input bit is 0, the NOT operation returns 1, and if the input bit is 1, it returns 0.

a |

0 |

1 |

|---|---|---|

~a |

1 |

0 |

Multiple Bits

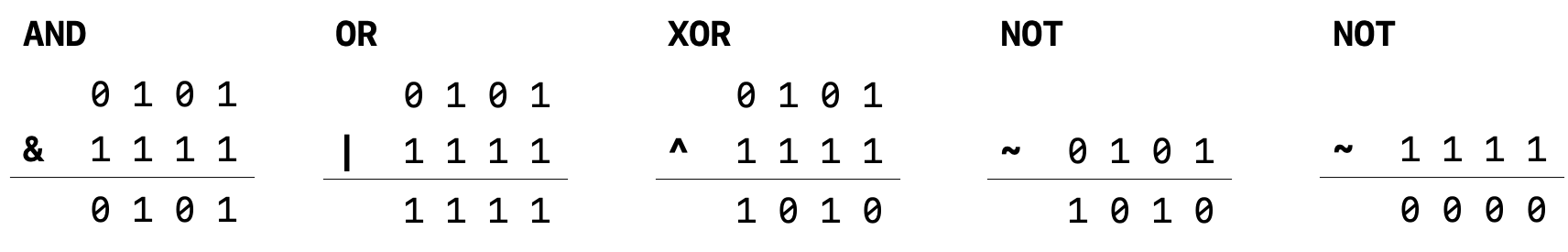

In order to apply these four bitwise operations to a string of bits, you simply perform the desired operation bitwise. For example, consider the two strings of bits 0101 and 1111. We can do the following example operations:

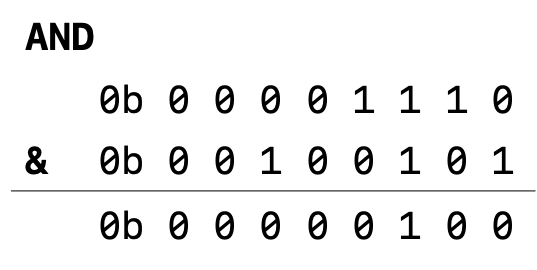

Let’s try a more complicated example. Consider the binary numbers 00001110 (represented as the variable a) and 00100101 (represented as the variable b). We can perform the bitwise operations in the following manner (press the green :arrow+forward: button below to run the program).

After running the code, it is clear that the results seem a bit confusing. This is because C will automatically represent integers as base-10 in stdout, the standard output. However, we can explain each of these results through converting binary strings to signed base-10 integers.

Recall that the lines of code int8_t a = 0b00001110 and int8_t b = 0b00100101 create a set of binary numbers (as indicated by the 0b prefixes), which represent signed integers with a total of 8 bits (as indicated by the int8_t variable type. Based on the two’s complement representation of signed integers, the base-10 representation of a and b can be found as

$$\texttt{a}=-2^7(\texttt{0})+2^6(\texttt{0})+2^5(\texttt{0})+2^4(\texttt{0})+2^3(\texttt{1})+2^2(\texttt{1})+2^1(\texttt{1})+2^0(\texttt{0})=14$$

$$\texttt{b}=-2^7(\texttt{0})+2^6(\texttt{0})+2^5(\texttt{1})+2^4(\texttt{0})+2^3(\texttt{0})+2^2(\texttt{1})+2^1(\texttt{0})+2^0(\texttt{1})=37$$

These explain the output values of a: 14 and b: 37 from running the program. Similarly, to calculate a & b,

Converting this to base-10 using two’s complement,

$$\texttt{a & b}=-2^7(\texttt{0})+2^6(\texttt{0})+2^5(\texttt{0})+2^4(\texttt{0})+2^3(\texttt{0})+2^2(\texttt{1})+2^1(\texttt{0})+2^0(\texttt{0})=4$$

This indeed gives us the result given by the code sample above.

Problem 1: Show that a | b, a ^ b, ~a, and ~b indeed give the expected results from the code output through performing a similar analysis as we did for analyzing a & b from above. Solution

Left Shift Operator

The next two operations that we will discuss – left shift and right shift – are not technically bitwise operations, as they are only relevant when we are working with a string a bits. Nonetheless, they are still very useful operations, and so they are helpful to discuss.

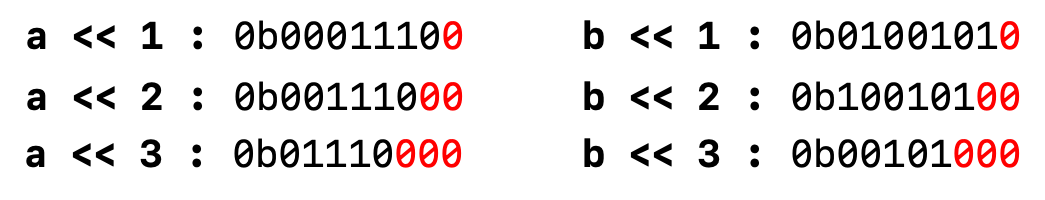

The left shift operator shifts all of the bits of a binary string to the left by $n$ places, where $n$ is any positive number. In order to “fill” the $n$ empty digits to the right, we simply add $n$ 0’s to the right at the end. For example, say that we have the same strings of bits a and b from the example above:

int8_t a = 0b00001110;

int8_t b = 0b00100101;

Here are some example results for the left shift operator:

The red zeros represent the added zeros due to the left shift.

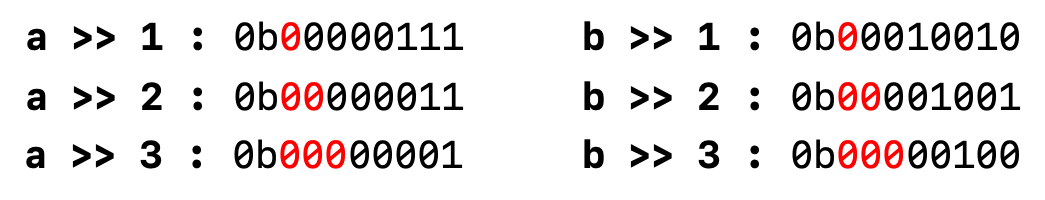

Right Shift Operator

As you can probably guess from our discussion on the left shift operator, The right shift operator shifts all of the bits of a binary string to the right by $n$ places, where $n$ is any positive number. In order to “fill” the $n$ empty digits to the left, we simply add $n$ 0’s to the left at the end. For example, say that we have the same strings of bits a and b from the example above:

int8_t a = 0b00001110;

int8_t b = 0b00100101;

Here are some example results for the left shift operator:

The red zeros represent the added zeros due to the right shift.

Other Bitwise Operations

There are other bitwise operations, but unless you have a strong interest in hardware and programming low-level electronic systems as an electrical engineer, they are not particularly relevant to our discussion here. If you are interested in learning more, I recommend checking out this Wikipedia link.

Why Should I Care?

So far, all of these bitwise operations seem like “novelty operations.” They seem cool, but what immediate purpose do they serve?

It turns out that bitwise operations can be cleverly manipulated to make complex calculations faster and more efficient. To illustrate their utility, we’ll look at a couple of example problems:

Example 1: Compute the additive inverse of $x$.

Consider our example problem from above illustrating the NOT operation. We can observe that if we take the NOT of the binary representation of int8_t a = 14;, we got ~a = -15. Similarly with int8_t b = 37;, we found ~b = -38. Based on these results, we might hypothesize that

The additive inverse of x is ~x + 1.

This is indeed the case, and allows us a quick and efficient method to compute \(-x\) using the NOT operation. The proof of this fact is fairly straightforward. Consider the sum of x and ~x:

We can conclude that any pair of $\texttt{x}$ and $\texttt{~x}$ will give us this result because for any binary digit that $\texttt{x}$ has, $\texttt{~x}$ will have the other binary digit, and so summing the two will always give the binary digit $\texttt{1}$ for every digit in the binary number. Therefore,

\[\texttt{x} + \texttt{~x}=-2^n+(2^{n-1}+2^{n-2}+\cdots+2^0)=-1\]Simplifying the right hand side to $1$ may not be entirely obvious, so I encourage you to try it out for a couple of test values for $n$ to confirm that this is true. Rearranging sides of this equation, we have

\[-\texttt{x}=\texttt{~x}+1\]as expected. Obviously, this only works with signed integers, as it doesn’t make sense to take the additive inverse of an unsigned integer.

Example 2: Multiply or divide an unsigned integer by $2^n$.

Let’s go back to our example on the left shift operator and [right shift operators], and write the base-10 representations of each of the results. Since we are focusing our attention on unsigned integers, we will recast our variables a and b as unsigned integers. We can use uint8_t and still keep the same bits as our signed integer representations, since our numbers are less than 128 and nonnegative in base-10. While we now have the framework to do this by hand, let’s just write code instead to make our lives easier:

As we can see here, shifting all of the bits left by 1 seems to multiply the base-10 representation by 2. This hypothesized pattern is indeed true:

Left-shifting an unsigned integer by $n$ bits multiplies the integer by $2^n$.

Of course, this fails once the multiplication result yields a value greater than the maximum allowed integer that can be represented by 64 bits, but unless you are expecting to have to perform many left shifts, this is often not a problem.

Based on this example, our first guess for dividing an integer by $2^n$ might be to right shift by $n$. It turns out for unsigned integers, this works perfectly well:

Right-shifting an unsigned integer by $n$ bits divides the unsigned integer by $2^n$.

Here are a couple of examples, using the same choices for a and b as we have above.

In the case where the number is odd, we can see from the examples that the result rounds down. For example, 7 / 2 rounds down to 3 in the example from above. From our previous experience in computer programming, this is exactly how integer division works in computer science.

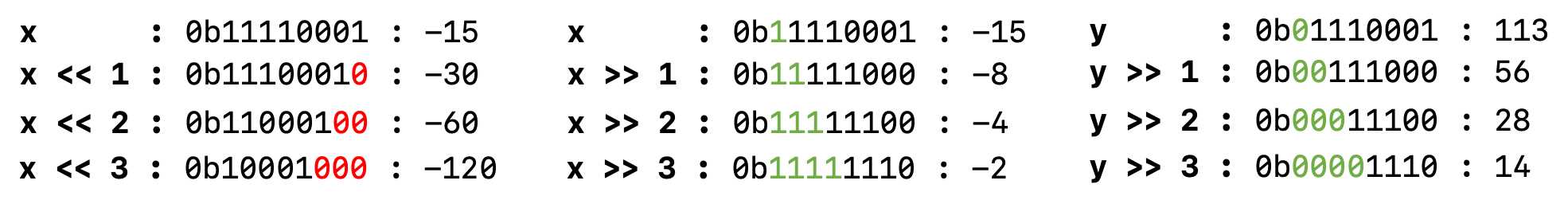

Example 3: Multiply or divide a signed integer by $2^n$.

To multiply a signed integer by $2^n$, the process is exactly the same as multiplying an unsigned integer by $2^n$: all we need to do is move every single digit to the left once, and then add the appropriate number of zeros at the end. However, dividing a signed integer by $2^n$ is a bit more complicated.

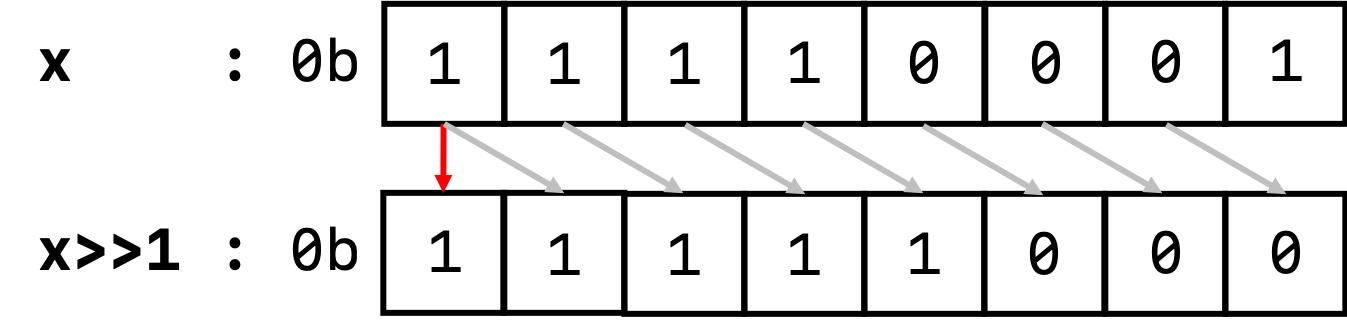

Let’s imagine that we have a signed integer int8_t x = 0b11110001, and we would like to divide this number by 2. Simply moving every digit to the right by one is not valid because adding a 0 as the left most digit would necessarily change the sign of this integer from negative to positive. In order to preserve the sign, we should keep the left most digit as is. Graphically, this could look something like

The red arrow indicates that we keep the most significant in order to preserve the sign of the number. Once we account for this, the right shift operation becomes entirely valid for signed integers. Here are a couple of examples of using the left shift and right shift operations in action, using int8_t x = 0b11110001 and int8_t y = 0b01110001:

Notice that according to this convention, x << 1 rounds to -8 instead of -7. This poses a discrepancy when dividing odd negative numbers through right shifting. If x is negative, then x >> 1 rounds downwards towards $-\infty$. However, x / 2 rounds upwards towards $+\infty$.

Logical vs. Arithmetic Shifts

The differences in right shift operations for signed and unsigned integers introduces a distinction between two types of common shift operations: logical and arithmetic. Put succinctly, logical shifts treat the numbers solely as binary strings and add zeros when necessary, while arithmetic shifts treat the numbers as signed integers and account for the sign of the number according to the two’s complement convention.

Here is a good summary table:

| Shift Operation | Logical | Arithmetic |

|---|---|---|

| Left Shift | Used for unsigned integers. Multiplies by $2^n$. Shifts digits over to the left $n$ times, and adds $n$ 0's to the right. Identical to left arithmetic shift. |

Used for signed integers. Multiplies by $2^n$. Shifts digits over to the left $n$ times, and adds $n$ 0's to the right. Identical to left logical shift. |

| Right Shift | Used for unsigned integers. Divides by $2^n$. Shifts digits over to the right $n$ times, and adds $n$ 0's to the left. Round down towards $-\infty$. Not identical to right arithmetic shift. |

Used for signed integers. Similar to dividing by $2^n$, but rounds down towards $-\infty$ instead of rounding up towards $+\infty$. Shifts digits over to the right $n$ times, and adds the left-most, most significant bit $n$ times. Not identical to right logical shift. |

In C, logical shifts are naturally used when a shift operation is called on an unsigned integer, such as uint8_t. Arithmetic shifts are naturally used when a shift operation is called on a signed integer, such as int8_t. A more extensive discussion of logical shifts is found in example 2 from above, while arithmetic shifts are discussed in example 3. Further discussion can be found here.

Additional Examples

A list of cool and common examples of using bitwise operations to perform calculations is linked here. I encourage you to check it out!

Integer Overflow

Let’s imagine that we’re trying to multiply the signed integer 0b01110001 by 2. As we have discussed above, this involves left shifting all of the bits by one place, which at first pass would suggest that the result should be 0b11100010.

However, something seems wrong with this result. At first glance, the left-most, most significant bit in the original integer is 0, meaning that the number is positive. However, after left shifting all of the its, the most significant bit now is 1, indicating that the number is now negative based on the two’s complement convention. This is strange: multiplying a positive number by 2 shouldn’t yield a negative number!

To get a better sense of what is happening here, let’s convert each of these signed numbers into their base-10 forms:

int8_t x = 0b01110001;

int8_t y = x << 1;

$$\texttt{x}=-2^7(\texttt{0})+2^6(\texttt{1})+2^5(\texttt{1})+2^4(\texttt{1})+2^3(\texttt{0})+2^2(\texttt{0})+2^1(\texttt{0})+2^0(\texttt{1})=113$$

$$\texttt{y}=-2^7(\texttt{1})+2^6(\texttt{1})+2^5(\texttt{1})+2^4(\texttt{0})+2^3(\texttt{0})+2^2(\texttt{0})+2^1(\texttt{1})+2^0(\texttt{0})=-30$$

In this case, we seem to violate the “left shift is multiply by 2” rule from above! Let’s see if we can explain what is happening.

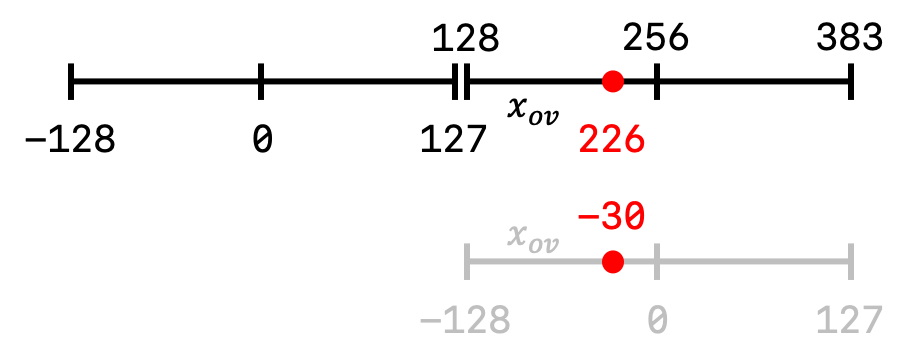

It turns out that this apparent “issue” is related to the fact that we can only represent a set range of numbers using a finite set of bits (in this case, 8 bits). Recall that the range of allowed int8_t signed integers is -128 to 127. Multiplying x by 2 would be 226, which is certainly outside the range of what can be represented using int8_t’s. In other words, we have an instance of integer overflow.

In C, your computer typically deals with this by carrying over the overflow, which can be thought of like this:

Essentially, when the number exceeds the bound of what can be represented using the int8_t type, the value represented by the int8_t can be found by “shifting” the range of allowed integer values, such that we are left with an integer amount that can be represented by the integer type. In this example, since 226 is greater than 127, we can think of finding the distance $x_{ov}$ that is overflown from the left bound, and essentially take it from -128 instead. In this example, the overflown amount from the actual number line is

We can then add the overflown amount to the “adjusted” left bound to get the actual result from x << 1:

This gives us the expected result! We can see that by adjusting for integer overflow, we can explain some strange arithmetic results in certain cases.

Problem 2: Using a similar analysis and diagram as above, explain the result of the following code:

int8_t a = 0b10001110;

int8_t b = a << 1;

printf("a: %hhu\n", a); // Prints a: -114

printf("b: %hhu\n", b); // Prints b: 28

In a way, accounting for signed integer overflow can be thought of a lot like the angles on a unit circle. We often only want to represent angles $\theta\in[0, 2\pi)$, and so if we have an angle of, say, $\theta=3\pi$, we might want to subtract off the range of $2\pi$ to get $\theta_{\text{adj}}=3\pi-2\pi=\pi$, which still represents the same angle but is in the desired range $[0, 2\pi)$. The remaining $\pi$ can be thought of the “overflow” in this case.

Fortunately, in practical C programming, we often don’t need to think too much about signed integer overflow. This is because unless the variable type of a<<1 is explicitly declared, C will automatically increase the variable number of bits to allow for the desired operation to be mathematically sound. Let’s investigate this through the following example:

There is a lot happening here. Let’s break it down piece by piece.

We have three types of signed integers: int8_t s, int16_t m, and int32_t l. Note that because they all have a 1 as the most significant bit, they all run the risk of signed integer overflow.

Line 9 of the code will print out the values of each of our three variables in base 10, in addition to the value of (long)l in base 10. Note that (long)l is simply casting the 32-bit integer l into a 64-bit integer l with the same value. Therefore, l and (long)l should print out the same base-10 value.

Lines 11-14 will print out the sizes of each of the variables in bits. Per our understanding of integer sizes, we know that they have the following sizes:

| Variable | Variable Type | Size |

s |

int8_t |

8 bits |

m |

int16_t |

16 bits |

l |

int32_t |

32 bits |

(long)l |

long |

64 bits |

Lines 16-19 will investigate the sizes of s<<1, m<<1, and l<<1. Because all of s, m, and l have the issue of signed integer overflow, **they will all be scaled up to the size of int32_t (32 bits). Note that while this resolves the issue for s and m, l was initially 32 bits, and would need 64 bits in order to return the correct value. In order to correct for this, we can cast l to a long first with 64 bits and then left shift the bits. This will allow (long)l<<1 to be 64 bits instead of 32 bits.

Finally, lines 21-25 confirm that we achieve the correct values for doubling either s, m, or l. Note that for doubling l, l<<1 gives an incorrect result, while (long)<<1 gives the correct result, as expected.

Integer overflow also happens with unsigned integers in a similar way as above.

Additional Exercises

Problem 3

The following code in main(void) swaps the values of two int variables n1 and n2 using only bitwise operations. Explain how this function works.

Problem 4

The following method add(int x, int y) adds two ints x and y using only bitwise operations. Explain how this function works.