Pointers in C

Today, we’ll be learning about pointers in C programming, which can essentially be thought of as address to certain locations in primary memory storage. While this may sound straightforward, pointers are often considered to be one of the most confusing subjects for students just beginning to learn C. In order to illustrate how to use pointers and related concepts, we’ll be referring to the following code in repl.it throughout the entirety of this lesson. I encourage you to follow along by opening the repl in a new tab and also participating in the exercise!

Part 1

For this section, make sure for the MACROS at the top of the repl match this exactly:

#define PART1 // Enables Part 1

#undef PART2 // Disables Part 2 for now

#undef PART3 // Disables Part 3 for now

The Basics

A pointer is a variable whose value is the address of another variable. On 64-bit systems (that is, most modern computers), all pointers are 64 bits, or 8 bytes. On older 32-bit systems, you may come across pointers that are 32 bits instead. Pointers are represented in C in the following format:

thing_you're_pointing_to *pointer;

pointer is the name of the pointer that we’re declaring, and thing_you're_pointing_to is the variable type of the object that our particular pointer pointer is pointing to. For example, let’s say that pointer was pointing to an address where a char was stored. Then, the pointer declaration should look like char *pointer;. The * indicates that we are dealing with a pointer.

A generic pointer that points to a particular place in memory but does not give any information to exactly what variable type we’re pointing to is a void * pointer. For example, in line 15 above, the pointer v_ptr is a void * pointer, and points to a dynamically allocated space in primary memory that is 8 bytes large (sizeof(int64_t)). We haven’t talked above the malloc() function in detail yet, but this is essentially what the function does.

void *v_ptr = malloc(sizeof(int64_t));

This pointer is pointing to a particular memory location, as indicated by the 64-bit pointer to address: field in stdout. For me, I ran the code and saw that v_ptr was pointing to the memory address 0x1900260, but because the memory is dynamically allocated after compile-time, it will be different every time you run the code.

Pointer Dereferencing

Line 19 highlights an example of how we can dereference pointers, which is indicated by the left, outermost * operator.

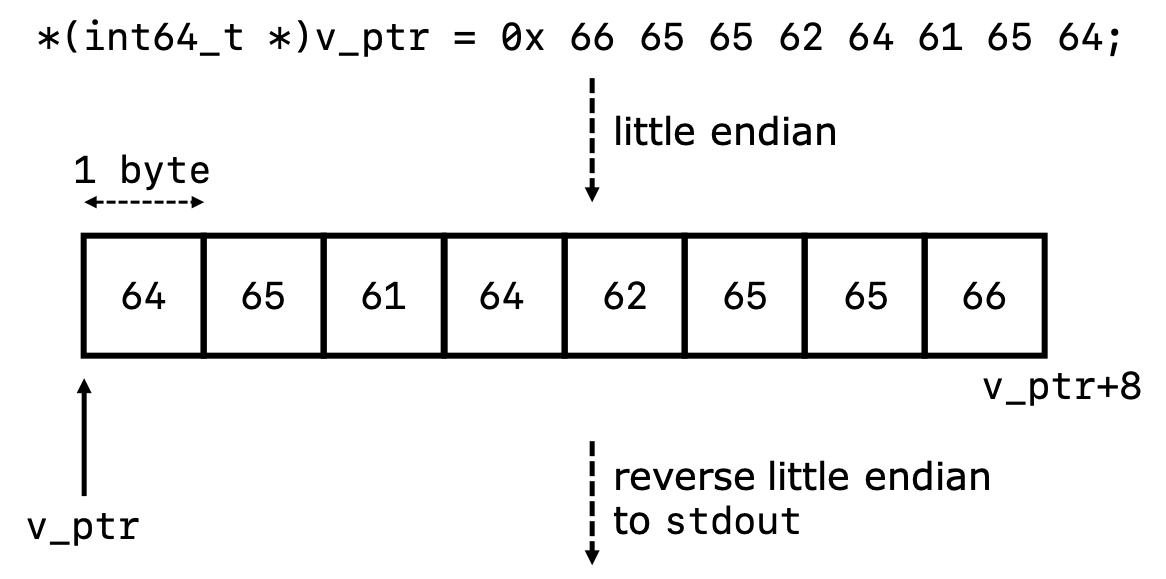

*(int64_t *)v_ptr = 0x6665656264616564;

Dereferencing essentially means that we are interested in reading/changing the value stored at the memory address pointed to by the pointer. The (int64_t *) part is a pointer casting operation (we will talk about this next), and effectively tells us to treat the value stored at that memory address as an int64_t, as opposed to a char or something like that. Effectively, this line of code tells us to store the value 0x6665656264616564 at the particular memory location pointed to by the v_ptr pointer. You can see that this is verified from the printf() statement in line 22, which prints out this set value in the hex bytes (64-bit): part of the printed output to stdout.

Pointer Casting

Recall that from the perspective of your computer, everything is simply just bits and bytes. How it is interpreted and then printed out to stdout for us to read as programmers depends on how we tell the computer to interpret the bytes. Should the bytes represent a number? An array of characters? Something else? Especially as a void * pointer, it is currently unclear how we would like the computer to interpret these bytes at this particular memory address. Let’s first consider line 23.

printf("int8_t: %hhd.\n", *(int8_t *)v_ptr);

What’s happening here is that we are casting the v_ptr pointer as a int8_t * pointer, meaning that we’re treating the thing at the memory address pointed to as a int8_t object. This means that we are only reading the first byte of the memory address, since an int8_t is only one byte large. Recall that the * operator reminds us to dereference the pointer, such that we know to print the int8_t stored at the memory address, not print the memory address itself. In little endian convention, based on the value we set at this memory address above, the first byte is 0x64, which corresponds to 100 in base 10 as a signed integer. This agrees with the result printed in stdout.

*(int8_t *)v_ptr = 0x64 = 100 // 1 byte

*(int16_t *)v_ptr = 0x6564 = 25956 // 2 bytes

*(int32_t *)v_ptr = 0x64616564 = 1684104548 // 4 bytes

*(int64_t *)v_ptr = 0x6665656264616564 = 7378415037781730660 // 8 bytes

This agrees with the results printed to stdout from the repl above. (I’ve skipped over the calculations to convert from hexadecimal to base 10, but if you don’t believe me, try using this calculator to verify this work.

Of course, we can also cast our pointer as a char * array as well, as done in line 27 of the repl. This tells the computer to treat the byte stored at the memory address pointed to by v_ptr as a char, and so

*(char *)v_ptr = 0x64 = 'd' // 1 byte

This follows the ASCII convention, as linked here. We can also print an array of characters of varying length, as indicated by lines 28 and 29. Here, the argument (int)sizeof(*(int32_t *)v_ptr) tells us the number of bytes from the array to print. Casting as a int32_t * pointer tells us to treat the thing at v_ptr as a 4-byte object, and so dereferencing the pointer gives us 4-bytes back. Therefore, this sizeof() function will return 4 bytes. (char *)v_ptr has casted v_ptr as a char * pointer and points to the beginning of the char array to begin printing. The same argument holds for line 29.

Problem 1: Validate that lines 28 and 29 give the expected output to stdout.

Part 2

For this section, make sure for the MACROS at the top of the repl match this exactly:

#undef PART1 // Disables Part 1 for now

#define PART2 // Enables Part 2

#undef PART3 // Disables Part 3 for now

Overwriting Bytes

As we can see from the output from line 37, we have a combination of bytes stored at the memory location pointed to by v_ptr, due to the action of lines 19 and 35.

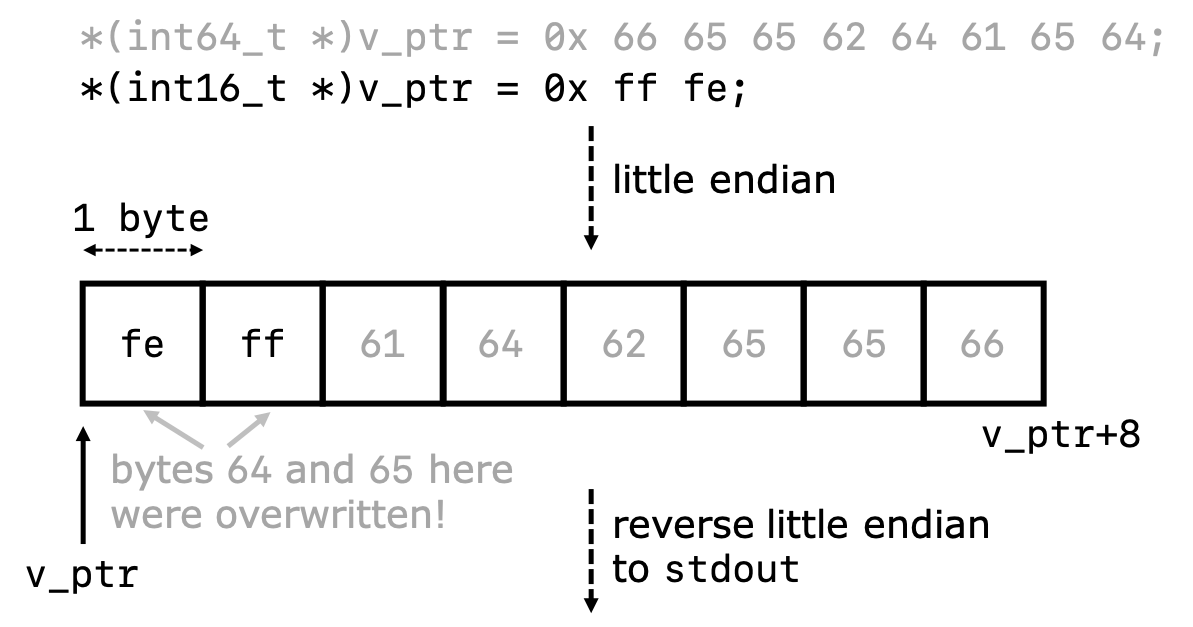

*(int64_t *)v_ptr = 0x6665656264616564;

*(int16_t *)v_ptr = 0xfffe;

What happens is that in the first line, the memory address becomes set to look like something very similar to what we saw in the diagram drawn in the above section. However, the next line overwrites the least significant bytes stored at the beginning of the memory address to be fffe.

*(int16_t *)v_ptr = 0xfffe = -2 // 2-byte signed integer

*(uint16_t *)v_ptr = 0xfffe = 65534 // 2-byte unsigned integer

*(int32_t *)v_ptr = 0x6461fffe = 1684144126 // 4-byte signed integer

Once again, you can use this calculator to verify that we did the hexadecimal to decimal conversions correctly if you’d like. This indeed gives us the expected results from written to stdout.

Part 3

For this section, make sure for the MACROS at the top of the repl match this exactly:

#undef PART1 // Disables Part 1 for now

#undef PART2 // Disables Part 2 for now

#define PART3 // Enables Part 3

Pointers to Pointers

The first new thing that we see is in line 45.

void **v_ptr_ptr = (void **)malloc(sizeof(void *));

We have briefly seen malloc() function before. We are asking malloc() to allocate size(void *) bytes of memory to us. Since a void * pointer is 8-bytes on 64-bit systems, we will receive (at least) 8-bytes of memory from this function.

Like the regular void * pointer, the void ** pointer is also a generic pointer, but in this case, it is a pointer to a pointer to a memory location. In other words, the void ** pointer points to a particular memory location, and whatever is stored at that memory location will be treated as a void * pointer to yet another memory location in primary storage. In other words, the void ** pointer features two levels of indirection in addressing memory.

When running the code, I get the following output from lines 16, 46, and 52:

64-bit pointer to address: 0x1881260.

64-bit pointer to pointer to address: 0x1881690.

hex bytes (64-bit): 0x1881260.

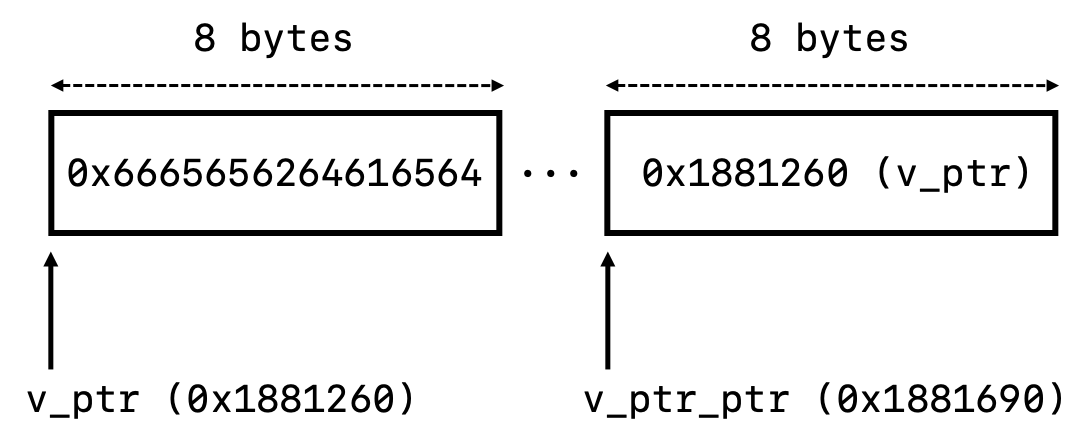

Again, because dynamic memory is allocated after the program is compiled, your values printed to stdout will almost certainly be somewhat different than mine, but regardless, the first and third results from above should be the same. Let’s go over the rational for what is happening here.

As discussed above, the malloc() call from line 15 returns a void * pointer to an 8-byte memory space for us to use. The pointer is pointing to the particular address at 0x1881260, according the first line of output above.

Furthermore, also as discussed above, the second malloc() call from line 45 also returns to us an 8-byte memory space fo us to use, and this space is designated as storing a void * pointer since we have cast our pointer to be a void ** pointer to a pointer. Similar to the earlier example involving the v_ptr void * pointer, line 46 will point out the address pointed to by our “pointer to a pointer.” In this case, the void ** pointer points to the memory address at 0x18881690, according to the second line of stdout output.

The third and last line hex bytes (64-bit): requires us to understand what is happening at line 50.

*v_ptr_ptr = v_ptr;

Recall that the single dereference operation * on the left hand side tells us that we’re talking about the thing stored at the memory address, not the memory address itself. This line of code is telling us to set the void * object that is being stored at the memory address pointed to by v_ptr_ptr to be the void * pointer v_ptr. Therefore, after this line of code, this is what the relevant locations of memory look like (ignoring any little-endian conventions for clarity):

This agrees with what is printed to stdout.

We can also “doubly” dereference the v_ptr_ptr pointer, which is equivalent to dereferencing the the v_ptr pointer that is being stored at v_ptr_ptr. This is what line 52 is doing, and confirms that it prints out the hexadecimal value being stored at the memory address pointed to by v_ptr.

printf("hex bytes (64-bit): 0x%lx.\n", **(int64_t **)v_ptr_ptr);

Problem 2:Try to add the following code sample at line 53 of the repl from above.

printf("triple dereference (64-bit): 0x%lx.\n", ***(int64_t ***)v_ptr_ptr);

What is the result? Can you explain it?

Retrieving Pointers Using the

&Operator

Next, let’s turn our attention to lines 47 and 48 of the code:

printf("64-bit pointer to pointer to address: %p.\n", &(*v_ptr_ptr));

printf("64-bit pointer address on stack: %p.\n", &v_ptr);

The & operator can be thought of as the opposite of the dereferencing * operator. It returns the address at which a variable itself is being stored at. For example, let’s consider the first line that is essentially printing out the value of &(*v_ptr_ptr). The *v_ptr_ptr dereferences the pointer to return the thing being stored at v_ptr_ptr, which is simply v_ptr itself. The subsequent & tells us to return address at which v_ptr is being stored at. However, as we have noted just now, v_ptr is being stored at the memory location v_ptr_ptr!. Essentially, we can think of & and * as inverse operations, so &(*v_ptr_ptr) essentially refers to the pointer v_ptr_ptr itself. The printed output agrees with this result.

What about the next line featuring &v_ptr? Why does it give a different result than the example immediately above? This particular instance of v_ptr is not referring to the v_ptr being stored locally at the memory address pointed to by v_ptr_ptr. Rather, it is referring to the local pointer variable in this function in C. Recall that local variables in C are stored on the stack in primary storage! The seemingly arbitrary output pointer printed to stdout validates this understanding: this pointer points to somewhere on the stack itself, where the v_ptr local variable is actually being stored.

To summarize, the & operator returns a memory address of the place in memory where the variable is being stored.

Cleaning Up

This program gives us a good idea of the utility of pointers and how we can use them in C. The generic pointer to a particular memory location is a void * pointer, but through casting pointers to different types of pointers, we are able to specify to our computer what type of object we are pointing to, and how it should be treated when manipulated and printed and whatnot. We also learned about how to use the associated & operator, the idea of pointers to pointers and understanding how primary memory is accessed and maintained by C programs.

The last thing that we have to do is free up the dynamical allocated memory used by our program due to the two malloc() function calls. In order to free up the memory, we call the stdlib.h function free(), as shown in lines 54 and 58 in the repl. We will discuss more about the malloc() and free() memory management functions in the future.