Maps and Hashing (Continued)

Learning Objectives: By the end of this learning module, you should understand how to...

- use the maps interface and its associated implementation in Java in the appropriate contexts and usage cases.

- build on your understanding of hashing and implement open addressing for collision handling.

- write your own map implementation.

Introduction

Last time, we discussed the Java set interface and introduced how hashing and hash functions could be used as an efficient way to implement sets. To continue this common theme of the use cases of hashing, we’ll be looking at the Java map interface today.

The Java map interface can be thought of as a dictionary (in fact, in some other programming languages it’s actually called a dictionary). Let’s think of what happens when we look up a word like “computer” on Merriam-Webster:

Of course, given that we’re programmers, we don’t actually care about the exact definition of what a computer is. What I do want to emphasize is the layout/format of this dictionary. We have a keyword (in this case, “computer”), which is associated with the definition or data value “a programmable usually electronic device that can store, retrieve, and process data.” In other words, there is a key-value relationship where every key has some value associated with it. A collection of key-value objects where all the keys are of a certain variable type and all the values are of a certain variable type is called a map.

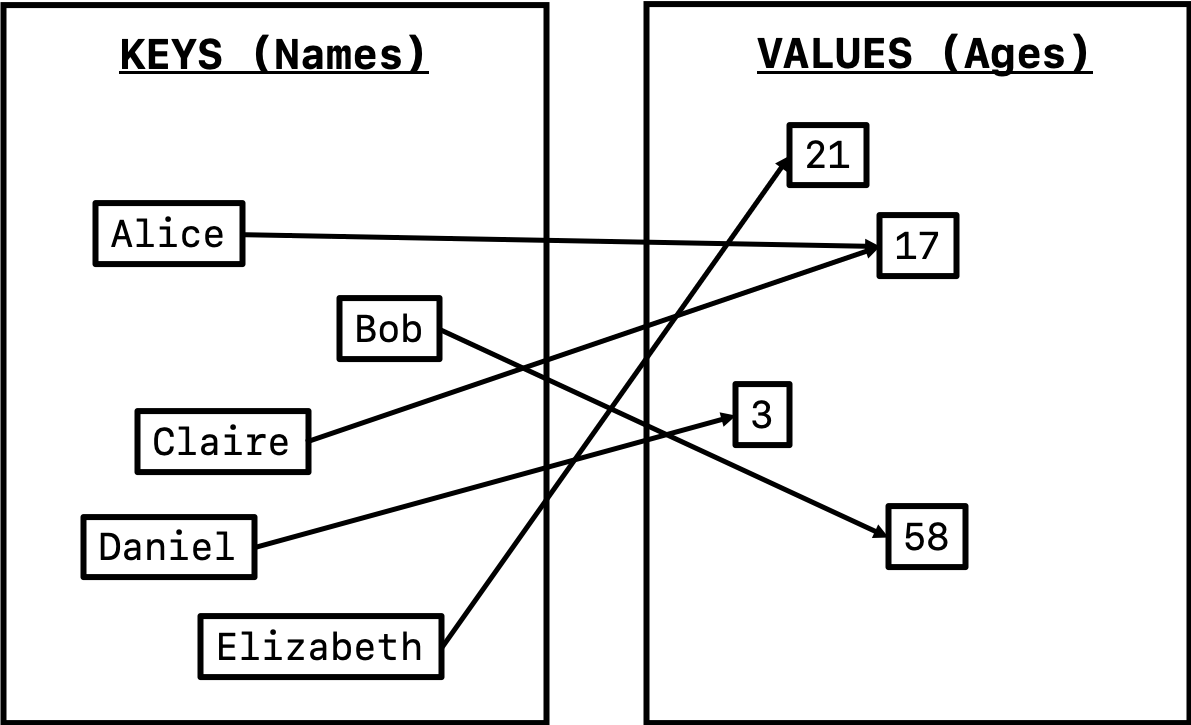

To give another example, we can describe a map where we have the names of individuals as keys and their age as the associated values. Note that all of the keys are strings and all of the values are integers. Let’s draw the map in the following way:

Here, this map represents 5 different people: Alice and Claire are both 17 years old, Bob is 58, Daniel is 3, and Elizabeth is 21. There’s a couple things that we want to note that representative about maps in general:

- Note that Alice and Claire, two distinct keys, map to the same value of 17. This is completely legal, as two people can have the same age! Two different keys can map to the same value.

- However, note that the same key cannot map to the multiple distinct values. For example, Alice cannot be both 17 years old and 58 years old at the same time! Every key can only map to one value.

- Every value must have a key. As an example, we can’t just have an age but have no person with that age.

- Every key must have a value. Similar to point (3) above, a person must have an age as well. Note that more generally, the value can be the Java

nullvalue, but regardless, thisnullvalue is still associated with the particular key.

Java Implementations

Now that we have an idea of what the Java map interface looks like, we can discuss how to actually implement them in standard code. To instantiate a map instance, the Java code can look something like

Map<K, V> myMap = new HashMap<>();

Here, myMap is the variable name of our new created map, K is the variable type of the keys in our map, and V is the variable type of the values in our map. As an example, going back to our example above on mapping String names to int ages, we can create an appropriate map using the following code:

Map<String, int> namesToAges = new HashMap<>();

Here’s a table of common methods that you can use with maps:

| Function | Description |

boolean containsKey(K key) |

Returns whether the map contains the input key key |

boolean containsValue(V value) |

Returns whether the map contains the input value value |

V get(K key) |

Returns the value associated with the key key. If the key is not found in the map, then this function returns null |

V put(K key, V value) |

Adds the key-value pair of key and value to the map. If key is already present in the map, then its value is replaced with value |

V remove(K key) |

Removes the key-value pair associated with key and returns value. If the key is not found in the map, then this function returns null |

Set<K> keySet() |

Returns a set of the keys in the map |

Collection<V> values() |

Returns a collection of the values in the map |

For example, to construct the map shown in the diagram above mapping String names to int ages, we might have code that looks something like

Map<String, int> namesToAges = new HashMap<>();

namesToAges.put("Alice", 17);

namesToAges.put("Bob", 58);

namesToAges.put("Claire", 17);

namesToAges.put("Daniel", 3);

namesToAges.put("Elizabeth", 21);

The complete list of map interface methods can be found in the official Java documentation here.

HashMaps vs.Hashtables

From the code above, you may have seen that our chosen Java implementation of the map interface is the HashMap. Another common Java implementation is the Hashtable, which can be instantiated very similar to what we saw above. For example, we could have just as easily written

Map<String, int> namesToAges = new Hashtable<>();

From the names of these implementations, you might guess that these implementations (once again) take advantage of hashing, which is correct. Similar to our discussion on sets from last time, both HashMaps and Hashtables store the key-value pairs in an array of buckets. The key-value pair is placed in the appropriate bucket as determined by the output of applying a particular hashing function on the key. Handling hashing collisions can be done through either separate chaining or open addressing, which we also discussed last time.

Both HashMaps and Hashtables using hashing to store key-value pairs for fast access speeds, and their respective speeds and performances are comparable. However, there are some subtle differences between the two implementations in Java. For us, perhaps the most important thing right now is that HashMaps allow for null keys and values, where Hashtable doesn’t allow for any null keys or values. One disadvantage of HashMaps is that HashMaps do not allow multiple computers to concurrently modify and read from the map at the same time. For these applications, you would be forced to use Hashtables. That being said, this idea of thread synchronization and concurrency is not something that we’ll have to worry about right now, so for the majority of our applications using the HashMap implementation is generally preferred.

Relationship to Sets

As a side note, you might notice that there are a lot of similarities between our discussion on maps and our discussion on sets from last time. This theme will be further echoed after completing the exercise below. The reason why this is is that a set is basically a particular version of a map where all of the values in the map are null or simply set to some dummy variable. Both are unordered collections of objects, and many of the same restrictions on the keys in maps are also valid restrictions on the elements in a set as well!

Exercises

In the following set of exercises, you will use your understanding of the map interface and open addressing to construct a simple database to store and access the personal information of an individual.

This is a fairly involved exercise and so we’ve tried to break it down piece by piece here. For that reason, it is strongly encouraged that you go through the following problems in the order that they’re presented.

To begin, navigate to the template repl at this link.

Problem 1

If you didn’t do Problem 1 from the last module on sets and introduction to hashing, then read about the open addressing technique for handling hashing collisions from GeeksforGeeks here.

Problem 2

Navigate to the HashNode.java source code file in the repl linked above. We can think of each HashNode instance as a key-value pair, where each String key is the name of an individual and each String[] value is the data associated with that individual. Implement the functions indicated in the HashNode.java file. For the hashCode() function, be sure to implement a “well-performing” hashing function that takes in an input String name and outputs an integer. Our suggestion is to use the hashing function discussed here for String inputs.

Problem 3

Navigate to the MyHashMap.java source code file in the repl linked above. Our map will be implemented as an array of HashNodes that we wrote in Problem 2 from above. Implement the remaining functions in the source code file. Handle collisions through open addressing with linear probing.

Problem 4

It’s finally time to run our repl. If your HashNode.java and MyHashMap.java code is correct, then the code should run with no errors. Once you’re done debugging, read through the driver test code in Main.java and make sure you understand what is happening. For the sake of testing the database, “names” (the keys of the map) are represented as Strings of random hexadecimal numbers, and “data” (the values of the map) are represented as the same Strings, just broken up as a String array of individual String characters.

Problem 5

Running the driver test code compares the speed of the containsKey() and containsValue() functions of your MyHashMap.java map implementation with Java’s official HashMap implementation. After running the code and observing the output speeds, answer the following questions:

- In general, which function is faster for a given implementation:

containsKey()orcontainsValue()? Can you rationalize your answer? (Hint: Which function can take advantage of hashing?) - Because Java’s implementation is written by professional programmers, we would expect our

MyHashMap.javaimplementation to be a bit slower than theHashMapimplementation. Is this what you observe? - You might see that your

containsValue()function is much slower than thecontainsValue()function from theHashMapJava implementation. Can you think of any ways to speed up yourcontainsValue()function? We encourage you to look up this problem on Google as well!