Introduction to Electrostatics (Solutions)

The following solutions are for the introductory electrostatics problems linked here. I encourage you to attempt them by yourself first before looking through the solutions.

Problem 1

In the early twentieth century, scientist Robert Millikan conducted a well-known set of experiments to try to determine the elementary charge $e$ of the electron. To summarize his experiment, he created a single oil drop of some mass $m$ and carrying a charge of $-q$ ($q>0$), and placed the oil drop between two conducting plates that created a uniform electric field $-E_0\hat{z}$ between the two plates.

- Draw a force diagram that illustrates the forces that are acing on the oil drop.

- Robert Millikan found that for an oil drop that weighed $1$ gram, he needed to apply an electric field of strength $E_0=5.7\times10^{-11}\frac{\text{N}}{\text{C}}$ in order for the oil drop to be suspended and not moving between the two plates. Using an appropriate force balance, calculate the total charge of the oil drop.

- At the time, the mass of the electron was known to be $m_e=9.1\times10^{-31}\text{ kg}$, assuming that the oil drop was entirely composed of electrons, calculate the charge of the electron.

- Compare your result from part 3 to the actual charge of an electron $e$. Are the results similar?

Part 1

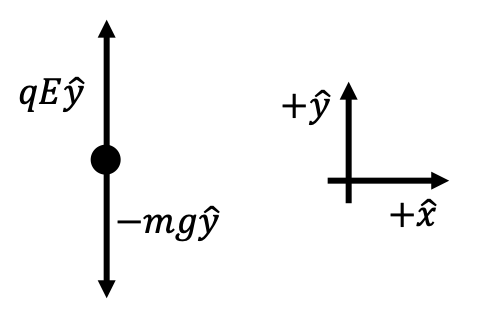

There are two forces that we need to account for: the force of gravity and the force due to the electric field. We know that the force of gravity is $-mg\hat{y}$, and the force of the electric field is $-qE_0(-\hat{y})=qE_0\hat{y}$, where $q>0$. We account for these two forces in the following force diagram:

Part 2

Because the oil drop was suspended and not accelerating, we know that the droplet was in mechanical equilibrium. Therefore, according to the force diagram from Part 1, we can conclude that

\[qE_0=mg\longrightarrow q=\frac{mg}{E_0}\]Plugging in the values given to us

$$q=\frac{0.001\text{ kg}\cdot10\text{ m}\cdot\text{sec}^{-2}}{5.7\times 10^{-11}\text{ N}\cdot\text{C}^{-1}}\approx1.75\times 10^8\text{ C}$$

Part 3

Using the given mass of an electron and the result from Part 2, we can calculate the magnitude $q_e$ of the charge of an electron.

\[\frac{1.75\times10^8\text{ C}}{0.001\text{ kg}}=\frac{q_e}{9.1\times 10^{-31}\text{ kg}}\]Solving for the magnitude of charge of an electron $q_e$ and then adding a negative sign to account for the fact that the electron is negatively charged gives

$$q_e\approx -1.59\times 10^{-19}\text{ C}$$

Part 4

According to Wikipedia, the actual charge of an electron is $-1.60\times10^{-19}C$. This tells us that our “experimental calculations” from Part 3 gave us a result that was pretty close to the real answer!

One thing to note is that for this problem, we simply made up the experimental values, but it is important to note that Millikan’s Oil-Drop Experiment was actually a real experiment! It was conducted a little differently than the way that we described it here, but the essential idea is there. If you’d like to read more about it, I recommend checking out this link here.

Problem 2

Calculate the electric field at any position $\vec{r}$ due to a hollow conducting spherical shell centered at the origin of radius $R_0$. The shell has a total charge $Q$ that is evenly distributed across its entire two-dimensional surface.

Because this is a conducting shell and we know that the electric field inside a conductor is zero, and so $E=0$ for $r<R_0$. Outside of the conducting shell, we know by symmetry that the electric field must be acting in the radial $\hat{r}$ direction, and should only depend on the magnitude $r$ of the position vector. This is because rotating the system about the origin doesn’t change what the sphere looks like, and so because the electric field must be unique, it cannot depend on anything else. Therefore, we can conclude that $\vec{E}=E(r)\hat{r}$ for some function $E(r)$ that we need to determine.

To determine $E(r)$, we can use Gauss’s Law, and draw a Gaussian spherical surface of radius $r>r_0$ also centered at the origin. Because we know that the electric field is only actin in the $\hat{r}$ direction, the flux is very simply $E(r)A$, where $A=4\pi r^2$, the surface area of the Gaussian surface. Meanwhile, the total charge enclosed is simply the total charge of the spherical shell, which is $Q$. Therefore, by Gauss’s Law, we can conclude that

\[\Phi=4\pi r^2E(r)=\frac{Q}{\varepsilon_0}\longrightarrow E(r)=\frac{Q}{4\pi\varepsilon_0r^2}\]and so the electric field due to this charged spherical shell is

$$\vec{R}=\begin{cases}0 & \text{ for }r<R_0 \\ \frac{1}{4\pi\varepsilon_0}\frac{Q\hat{r}}{r^2} & \text{ for }r>R_0\end{cases}$$

Problem 3

Consider an infinite, non-conducting plane sheet at $z=0$ that has a uniform surface charge density of $\sigma$. Calculate the electric field at any position $\vec{r}$ due to this sheet.

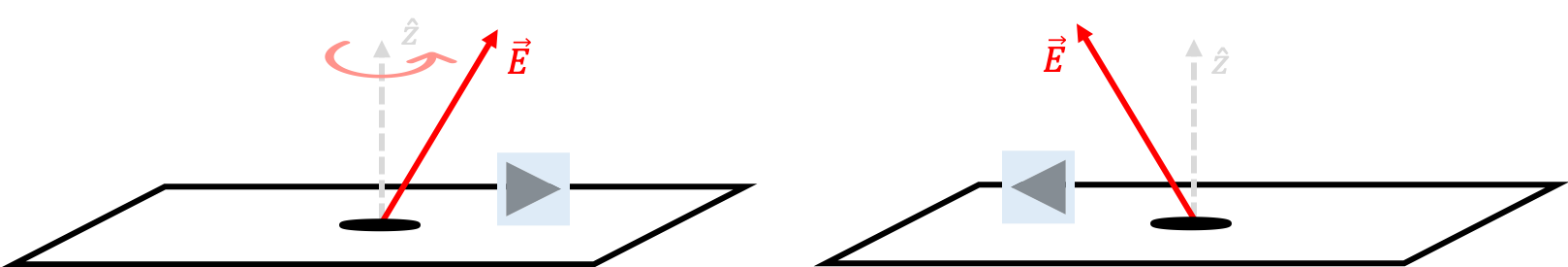

We know immediately by symmetry that the electric field must only be acting in the $\hat{z}$ direction, and can only depend on the $z$ coordinate (and not the $x$ or $y$ coordinates). If the electric field had any component in the $\hat{x}$ or $\hat{y}$ components, then we could simply rotate our entire coordinate system $180^{\circ}$ around the $z$-axis and the electric field would have inverted $\hat{x}$ and $\hat{y}$ components, but the system would look exactly the same! The electric field should be unique, so this tells us that the $\hat{x}$ and $\hat{y}$ components must be zero. This is depicted in the figure below. Even through the plane looks the same upon rotation, the electric field would look different, leading to a non-unique answer for the electric field. (The blue arrow is just to help act as a reference.)

Finally, along similar lines of reasoning, since we know that the plane is infinite, then translating our coordinate system in either the $\hat{x}$ or the $\hat{y}$ directions wouldn’t change anything. Therefore, the electric field cannot depend on either the $x$ or $y$ position coordinates.

By a similar symmetry argument we also know that the electric field is also always pointing away from the sheet. This is because we can simply invert the $\hat{z}$-axis and the system would look the same, and so once again we’re relying on a symmetry argument.

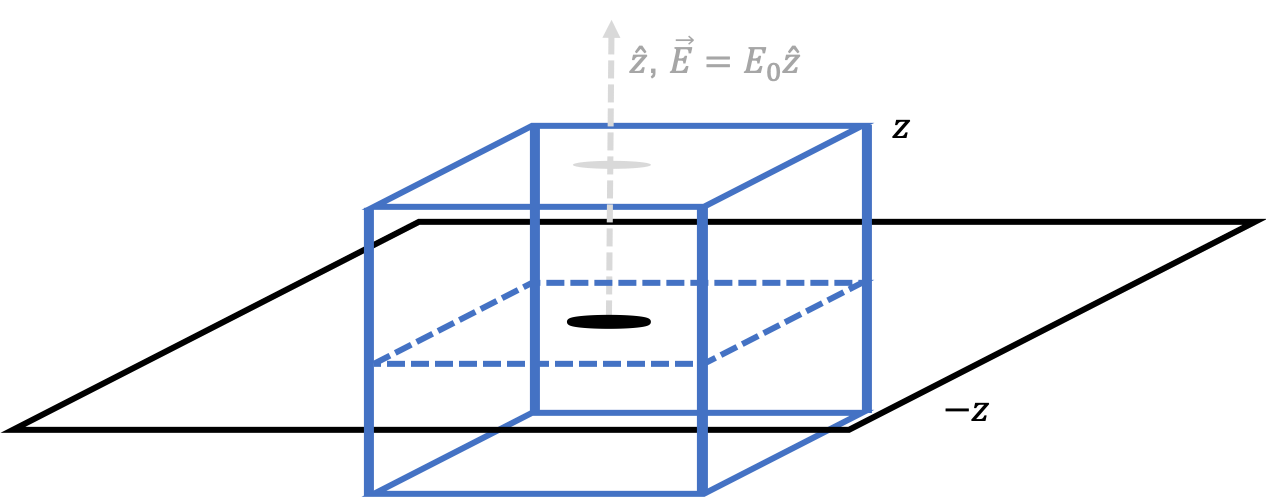

In order to calculate the electric field magnitude $E_0$ in the $\hat{z}$ direction for $z>0$, we can use Gauss’s Law. Consider a rectangular prism Gaussian surface from $z=-z$ to $z=z$, with base area $A$ and height $2z$.

The charged enclosed in this surface is only the charge from the infinite plane, and has value of $q_{\text{enclosed}}=\sigma A$. The total flux of the electric field through the box is the electric field flux through the top surface with magnitude $E_0A$ added to the flux through the bottom surface also with magnitude $E_0A$. Therefore, we can conclude that the total flux is $\Phi=E_0A+E_0A=2E_0A$, and so by Gauss’s Law,

\[\Phi=2E_0A=\frac{\sigma A}{\varepsilon_0}\longrightarrow E_0=\frac{\sigma}{2\varepsilon_0}\]Therefore, we can conclude that the electric field due to the presence of the infinite charged sheet at any location in space (except on the sheet itself) is

$$\vec{E}=\frac{\sigma}{2\varepsilon_0}\hat{z}$$

Problem 4

This problem is adapted from Serway Physics 9ed.

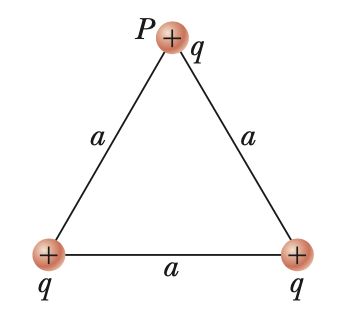

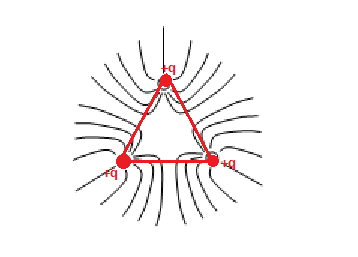

Three equal positive charges are at the corners of an equilateral triangle of side length $a$ as shown above. The three charges $q$ at the corners create an electric field.

- Sketch the electric field lines in the plane of the charges.

- Find the location of one point (other than at infinity) where the electric field is zero.

- What is the electric field at $P$ due to the two charges at the base?

Part 1

The field lines radiate out from the point charges (since they are positively charged) and look something like

Part 2

By symmetry, we can hypothesize that the electric field is also zero at the center of the triangle, which is the point inside the triangle that is equidistant from all three vertices. We can also prove this rigorously. Let’s define the center of the triangle to be at the origin, such that the three point charges are at the $(x, y)$ coordinates $\left(0, \frac{a}{\sqrt{3}}\right), \left(\frac{a}{2}, -\frac{a}{2\sqrt{3}}\right), \left(-\frac{a}{2}, -\frac{a}{2\sqrt{3}}\right)$ by geometry. Therefore, by the definition of the electric field, we know that the electric field at the origin due to the three point charges at the specified locations are

\[\vec{E}=\frac{q}{4\pi\varepsilon_0(a/\sqrt{3})^2}\left[(0\hat{x}+\hat{y})+\left(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\hat{x}-\frac{1}{2}\hat{y}\right)+\left(-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\hat{x}-\frac{1}{2}\hat{y}\right)\right]\]All of the vector components cancel out in both the $\hat{x}$ and $\hat{y}$ directions, and so $\vec{E}=0$ at the origin. Therefore, these confirms that

The electric field is zero at the center of the triangle, equidistant from all three vertices.

Part 3

Point $P$ is a distance of $a$ from both charges, and so the electric field $\vec{E}$ at point $P$ due to the other two point charges is

\[\vec{E}(P)=\frac{q}{4\pi\varepsilon_0 a^2}\left[\left(-\frac{1}{2}\hat{x}+\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\hat{y}\right)+\left(\frac{1}{2}\hat{x}+\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\hat{y}\right)\right]\]Simplifying this result gives

$$\vec{E}(P)=\frac{q\sqrt{3}}{4\pi\varepsilon_0a^2}\hat{y}$$