Friction

We briefly introduced the idea of friction last time when talking about mechanical equilibrium. Today, we’ll be delving more deeply into what friction really is.

Friction is a force that opposes the motion of objects, and always acts in the opposite direction (or intended direction) of the object. At a nanometer scale, friction arises because no surface is truly smooth, and so the different microscopic jagged edges will rub against each other to result in friction. This mechanism of how friction works is honestly not super important. There are two different types of friction: static and kinetic.

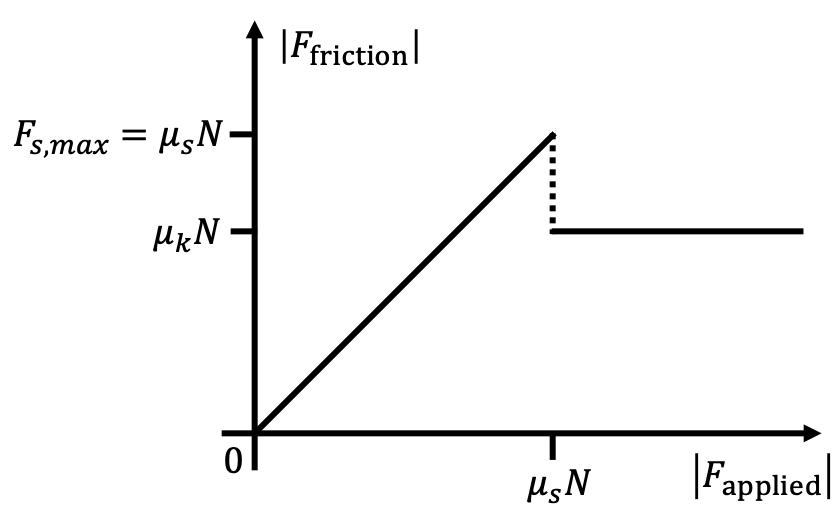

Static friction is the frictional force that prevents the motion of objects that are not currently moving. Consider the common example of me wanting to push a box across a floor. If I push the box with a tiny amount of force, the box is not going to move because the static friction will exactly match the force that I apply. In this way, static friction can be thought of as a “reactive force”.

Of course, eventually, assuming I’m strong enough, I’ll apply so much force that I can overcome the maximum amount of static friction force possible, and eventually the object will begin moving. This introduces two ideas: (1) there is a maximum amount of static friction force, and (2) kinetic friction.

The maximum amount of static friction force is given by $\vert F_{s, max}\vert = \mu_s N$. Here, $N$ is the magnitude of the normal force acting on the object (as we defined last time in our discussion on mechanical equilibrium. $\mu_s$ is called the static coefficient of friction, and is a constant proportionality constant that is a measure of how “rough” the two materials area. For example, if I was pushing a box made out of sandpaper on a carpet floor, $\mu_s$ should be pretty big. On the other hand, if I was pushing a box made out of ice on an ice rink, $\mu_s$ would be pretty small. $\mu_s$ is usually given to you as some parameter of the problem.

One the force applied on an object exceeds $\vert F_{s, max}\vert = \mu_s N$, we transfer to the kinetic friction regime. Kinetic friction is independent of the force applied, and has a constant magnitude of $\vert F_{k}\vert = \mu_k N$. Here, $N$ is still the magnitude of the normal force acting on the object, and $\mu_k$ is the kinetic coefficient of friction. It’s very similar to $\mu_s$, but for almost all materials, $\mu_s>\mu_k$.

Let’s put this all together and draw a graph of what the frictional force $\vert F_{\text{friction}} \vert$ will be as a function of applied force $\vert F_{\text{applied}} \vert$: