Moment of Inertia and Rotational Energy (Solutions)

The following solutions are for the problems on moments of inertia and rotational energy linked here. I encourage you to attempt them by yourself first before looking through the solutions.

Problem 1

A disk, a hoop, and a solid sphere are released at the same time at the top of an inclined plane. They are all uniform and roll without slipping. In what order do they reach the bottom of the plane?

Let us assume that all three objects have a radius of $R$ and masses of $M$.

First, we need to calculate the moments of inertia of the three different objects. For the solid disk that is rotating around its central axis, it has two dimensions in the radial $\hat{r}$ direction and in the $\hat{\theta}$ direction in polar coordinates. The mass density is

\[\rho_{\text{disk}}=\frac{\text{total mass}}{\text{total area}}=\frac{M}{\pi R^2}\]Therefore, the differential element

\[dm=\frac{M}{\pi R^2}da=\frac{M}{\pi R^2} rdr\text{ }d\theta\]Using the definition of the moment of inertia, we have

\[I_{\text{disk}}=\frac{M}{\pi R^2}\int_0^{2\pi} d\theta\int_0^R r^3=\frac{2M}{R^2}\frac{1}{4}R^4=\frac{1}{2}MR^2\]For the thin, hollow hoop that is rotating around its central axis, it has one dimension in the $\hat{\theta}$ direction going around its circumference. The mass density is

\[\rho_{\text{hoop}}=\frac{\text{total mass}}{\text{total length}}=\frac{M}{2\pi R}\]Therefore, the differential element

\[dm=\frac{M}{2\pi R}rd\theta\]Using the definition of the moment of inertia, and also the fact that the edge of the hoop is always a distance $r=R$ from the axis of rotation, we have

\[I_{\text{hoop}}=\frac{M}{2\pi R}\int_0^{2\pi} d\theta\text{ }R^3=\frac{M}{2\pi R}(2\pi R^3)=MR^2\]From example 4, we know that

\[I_{\text{ball}}=\frac{2}{5}MR^2\]From the example on rotational energy, we know from conservation of energy that

\[Mgh=\frac{1}{2}Mv^2+\frac{1}{2}I\omega^2\]where $h$ is the height of the inclined plane and $v$ is the tangential speed of each of the objects at the bottom of the inclined plane. As we can see, since the left hand side is simply a constant, we can conclude that as $I$ increases, $v$ decreases. $v$ is a measure of how fast a given object accelerates down the inclined plane, and the faster the object accelerates, sooner it will get to the bottom of the inclined plane. Therefore, the order in which the objects arrive at the bottom of the ramp is the same as the order of the objects’ decreasing moments of inertia. Comparing the three moments of inertia, we can therefore conclude that

The solid sphere reaches the bottom of the plane first, followed by the disk, and then finally by the hoop.

Problem 2

Consider a solid cylinder rolling about its axis.

- The moment of inertia of a solid cylinder about its axis is $I=\frac{1}{2}mr^2$, where $r$ is the radius of the cylinder and $m$ is the mass of the cylinder. If you were able to understand examples 3 and 4 from above and have experience with multivariable calculus and multi-dimensional integrals, show that the moment of inertia of this object is indeed $I=\frac{1}{2}mr^2$.

- If this cylinder rolls without slipping, what is the ratio of its rotational energy to its kinetic energy?

For the solid cylinder that is rotating around its central axis, it has three dimensions in the radial $\hat{r}$ direction, in the $\hat{\theta}$ direction, and in the $\hat{z}$ direction in cylindrical coordinates. The mass density is

\[\rho_{\text{disk}}=\frac{\text{total mass}}{\text{total volume}}=\frac{M}{\pi R^2\ell}\]where $\ell$ is the height of the cylinder. Therefore, the differential element

\[dm=\frac{M}{\pi R^2\ell}dV=\frac{M}{\pi R^2\ell} rdr\text{ }d\theta\text{ }dz\]Using the definition of the moment of inertia, we have

\[I=\frac{M}{\pi R^2\ell}\int_0^{\ell} dz\int_0^{2\pi} d\theta\int_0^R r^3=\frac{M}{\pi R^2\ell}(\ell)(2\pi)\left(\frac{1}{4}R^4\right)\]Simplifying the right hand side gives

$$I_{\text{solid cylinder}}=\frac{1}{2}MR^2$$

therefore giving us the expected result for the moment of inertia of a solid cylinder. To answer the second part of the question, we can take inspiration from the example on rotational energy:

\[U_{\text{kinetic}}=\frac{1}{2}Mv^2, \quad U_{\text{rotational}}=\frac{1}{2}I\omega^2=\frac{1}{2}\frac{1}{2}MR^2\left(\frac{v}{R}\right)^2=\frac{1}{4}Mv^2\]where we have used the fact that $v=r\omega$ to relate the magnitudes of the tangential velocity and angular velocity. Taking the ratio of the two, we have

$$\frac{U_{\text{rotational}}}{U_{\text{kinetic}}}=\frac{\frac{1}{4}Mv^2}{\frac{1}{2}Mv^2}=\frac{1}{2}$$

Problem 3

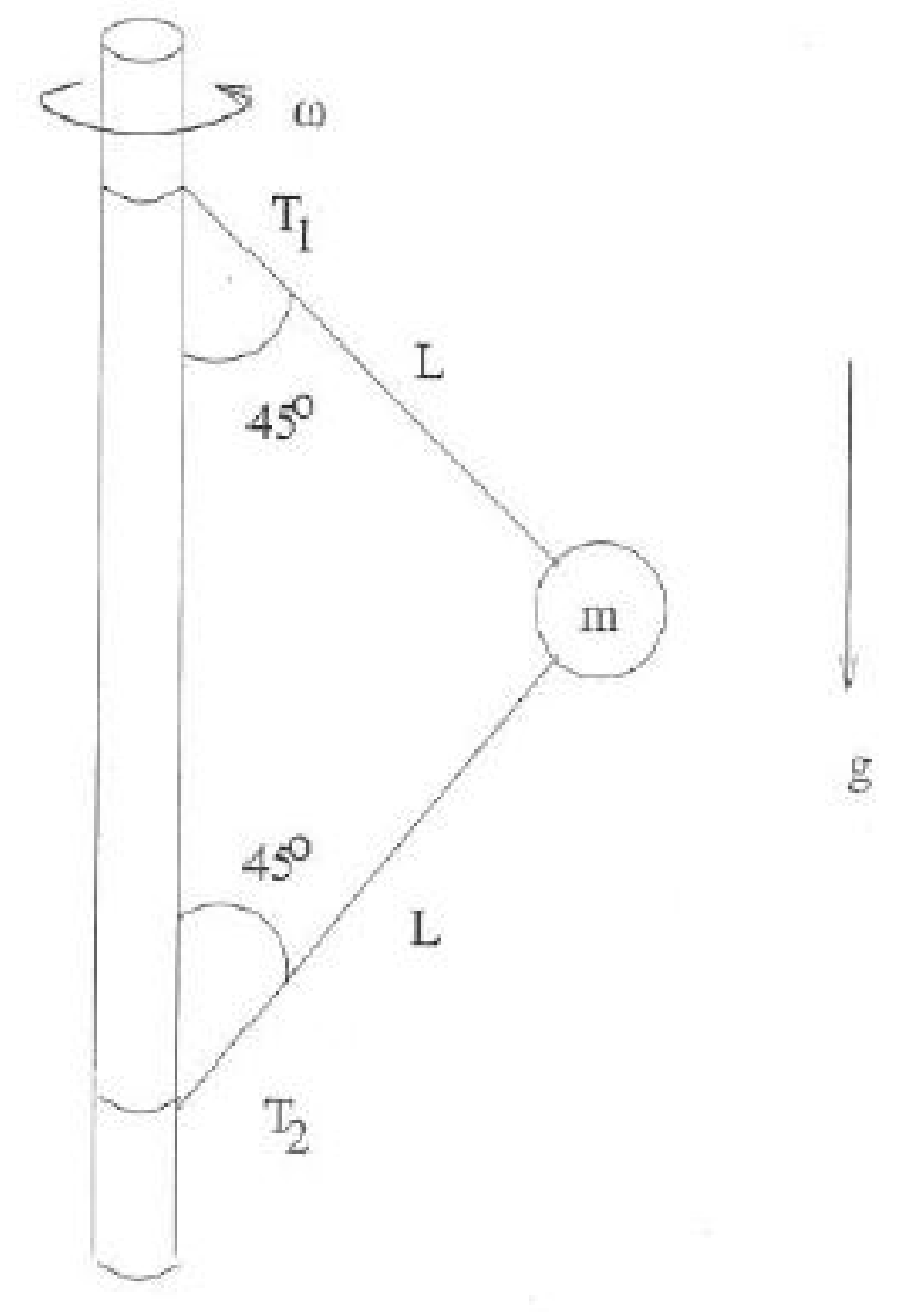

A mass $m$ is connected to a vertical revolving axle by two massless strings of length $L$, each making an angle of $45^{\circ}$ with the axle as shown.

Both the axle and mass are revolving with large angular velocity $\omega$. You may neglect the radius of the axle.

- Draw a free body diagram for the forces acting on the mass $m$.

- Find the tensions $T_1$ and $T_2$ in the two strings. Give your answer in terms of $\omega, m, L, g$.

- What is the minimum angular velocity $\omega_{\text{min}}$ such that both strings remain taut? Give your answer in terms of $\omega, m, L, g$.

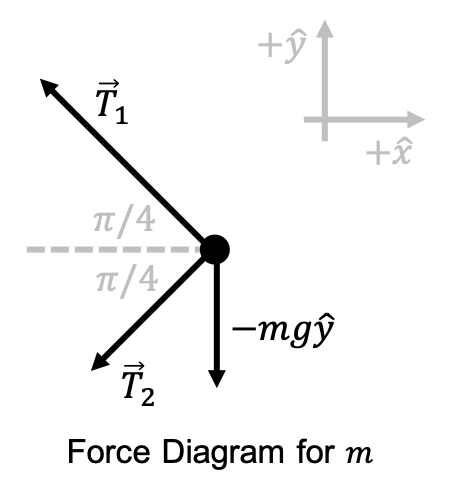

For the free body diagram, we need to account for the two tensions and the force due to gravity.

To find $T_1$ and $T_2$, we use Newton’s Law’s. The mass should not be accelerating in the $y$ direction, so

\[T_1\sin\left(\frac{\pi}{4}\right)-T_2\sin\left(\frac{\pi}{4}\right)-mg=0 \longrightarrow T_1-T_2=mg\sqrt{2}\]In the $\hat{x}$ direction, the mass should have a centripetal acceleration with magnitude $a_c$ “pulling” the ball towards the center in the $-\hat{x}$ direction to keep the mass rotating. Recall from our discussion on centripetal acceleration that the magnitude of $a_c=r\omega^2$ always. Therefore, we can conclude that

\[T_1\cos\left(\frac{\pi}{4}\right)+T_2\cos\left(\frac{\pi}{4}\right)=ma_c=mr\omega^2\]Now, we also use the fact that both of the strings attached to the mass are given to have length $L$. Therefore, by geometry we know that $r=L/\sqrt{2}$ and so

\[\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(T_1+T_2)=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}mL\omega^2 \longrightarrow T_1+T_2=mL\omega^2\]Solving the system of equations for $T_1, T_2$ gives

$$T_1=\frac{mL\omega^2+mg\sqrt{2}}{2}, \quad T_2=\frac{mL\omega^2-mg\sqrt{2}}{2}$$

Finally, to answer the last part of the question, a string remains taut (meaning that there is tension on it) when $T_i>0$. For $T_1$, this will always be the case, since $m, L, \omega, g$ are all positive quantities. However, for $T_2$, we need to ensure that

\[T_2=\frac{mL\omega^2-mg\sqrt{2}}{2}\geq0\]The minimum allowed value for \(\omega=\omega_{\text{min}}\) is therefore

\[\frac{mL\omega_{\text{min}}^2-mg\sqrt{2}}{2}=0\longrightarrow mL\omega_{\text{min}}^2=mg\sqrt{2}\]Solving this equation for \(\omega_{\text{min}}\) gives

$$\omega_{\text{min}}=\sqrt{\frac{g\sqrt{2}}{L}}$$