malloc()

In this section, we will talk about dynamic memory allocation in C, including the function malloc() and other related methods.

Static Memory Allocation

Consider the following line of code in C.

int x = 3;

As we have seen previously, all local variables are stored somewhere on the stack in primary storage, including the variable x above. When compiling the C source code to convert it into an executable, what happens is that the compiler tells the computer to allocate (i.e. set aside) space (on the stack) for this particular local variable. This operation is done before the program executes. In these cases for our standard set of local primitive variables like ints and chars, we can see that we cannot allocate variables through this method while the program is executing. This form of memory management is called static memory allocation.

Dynamic Memory Allocation

In certain cases, we may want the flexibility of being able to allocate computer memory during run time instead of before run time during the compilation process. This form of memory management is called dynamic memory allocation. Dynamic memory allocation can only allocate memory from the heap as opposed to the stack. The benefit of dynamic memory allocation is that we can often improve the space utilization of computer resources through effective dynamic memory management, but a downside is that the program may run a bit slower than if implemented in some other way because access times to the heap are often slower than access times to the stack.

malloc()

In C, dynamic memory allocation is accomplished using the malloc() library, which is included in the stdlib.h C library header file. This function

void *malloc(size_t size)

alllocates size bytes of memory from the heap and returns a void * pointer to the allocated memory address. If it happens that the heap has no additional space, then the function returns NULL since the request failed. As an example, malloc() can be used to store a String, which is simply an array of chars in C:

char *str = (char *)malloc(17); // Our string will have 17 characters.

strcpy(str, "This is a string!");

printf("%s\n", str, str);

If you are unfamiliar with the strcpy() function, I encourage you to check the documentation out here. This above code would print out This is a string! to stdout.

calloc()

The C library function calloc() is very similar to malloc() and is also used to dynamic memory allocation, usually for arrays with a predetermined number of elements. For example, let’s say that we want to allocate memory for n array elements that are size bytes each. The calloc() function does this as

void *calloc(size_t n, size_t size)

and returns a void * pointer to the beginning of the array (or NULL if the request fails). So, malloc() and calloc() are essentially identical if you set n = 1. However, a major difference is that malloc() simply returns a pointer to the beginning of the memory chunk, while calloc() returns a pointer to the beginning of the memory chunk and also zeroes out the allocated memory space. This means that the memory space is guaranteed to be filled with zero bits after the calloc() method call.

realloc()

realloc() is a standard C library function that resizes the memory block pointed to by ptr that was previously allocated with malloc() (or calloc()). The function

void *realloc(void *ptr, size_t size)

returns a pointer to the newly allocated memory, or NULL if the request fails. ptr is the pointer to the memory block previously allocated with malloc() or calloc(), while size is the new size for the memory block, in bytes. If ptr is NULL, then realloc() is exactly the same as malloc(). If size is 0, then realloc() is exactly the same as free().

free()

Just as we have to explicitly use the malloc() function to dynamically allocate memory during run time, we also need to dynamically deallocate (or free) memory during run time after we are done with a particular memory chunk in the heap. This is important for good space utilization of computer resources. This is accomplished using the free() function, which is also included in the stdlib.h C library header file. This function

void free(void *ptr)

will free a memory chunk previously allocated by a call of malloc(), realloc(), or calloc(). The argument ptr is a pointer to the memory block that we want to free. If NULL is passed in as the argument, then nothing happens.

Behind the Scenes

In the remaining part of this lesson, we will be going over the different memory management algorithms and how malloc() explicitly works “under the hood.”

Important Parameters

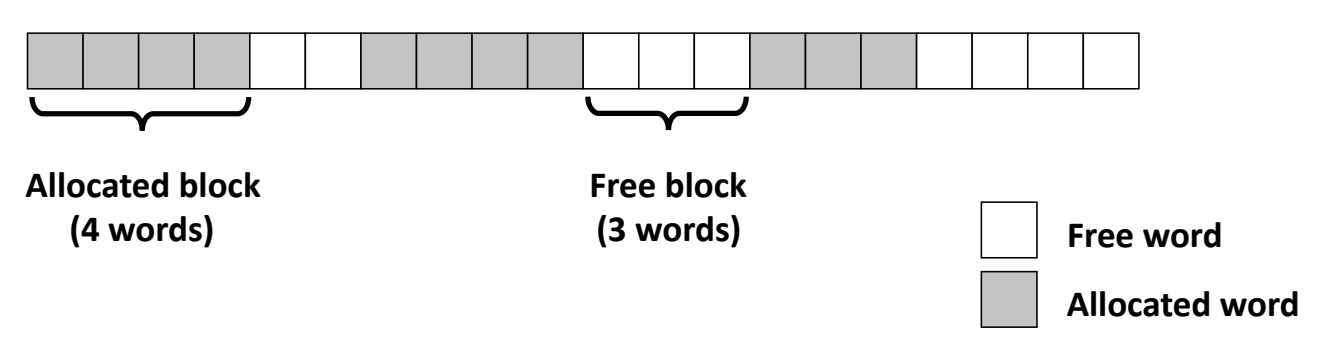

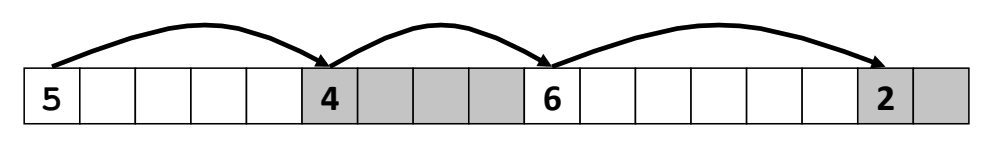

As always, we’ll imagine the heap as an array of blocks (that are each 8-bytes large on 64-bit systems). Because of various malloc() calls, at any given point, the state of the heap may look something like this, for instance:

Diagram taken from this link. Note that

Diagram taken from this link. Note that words should instead be quadwords because our blocks are 8-byte aligned.

As you can see here, at any given point in time we might have some sequence of allocated and deallocated “chunks” of memory that can be of varying and unknown lengths (since they are defined by the user). What are our goals for an effective malloc() implementation? There are primarily two things that we’re interested in:

- Throughput: This is the number of completed

malloc()requests per unit time. Essentially, how fast is ourmalloc()implementation? Note that this feature also somewhat depends on how fast the CPU of your computer is, and so when testing the throughput ofmalloc(), it is important to consistently use one standardized machine and run multiple tests for statistical significance. - Peak Memory Utilization: While throughput is a measure of time efficiency, peak memory utilization can be thought of as a measure of space and computer resource efficiency. Consider some sequence of

malloc()andfree()requests:

We define the aggregate payload $P_k$ is the collective size of all of the currently allocated payloads after request $R_k$ has been completed. Meanwhile, the current heap size is $H_k$ and is assumed to be monotonically nondecreasing. Our allocator can increase the size of the heap using the sbrk() function, discussed below. The peak memory utilization after $k$ requests $U_k$ is therefore defined as

Our goal in writing a malloc() implementation is to maximize throughput and peak memory utilization. However, as we will see, this can often become quite a challenging task.

Fragmentation

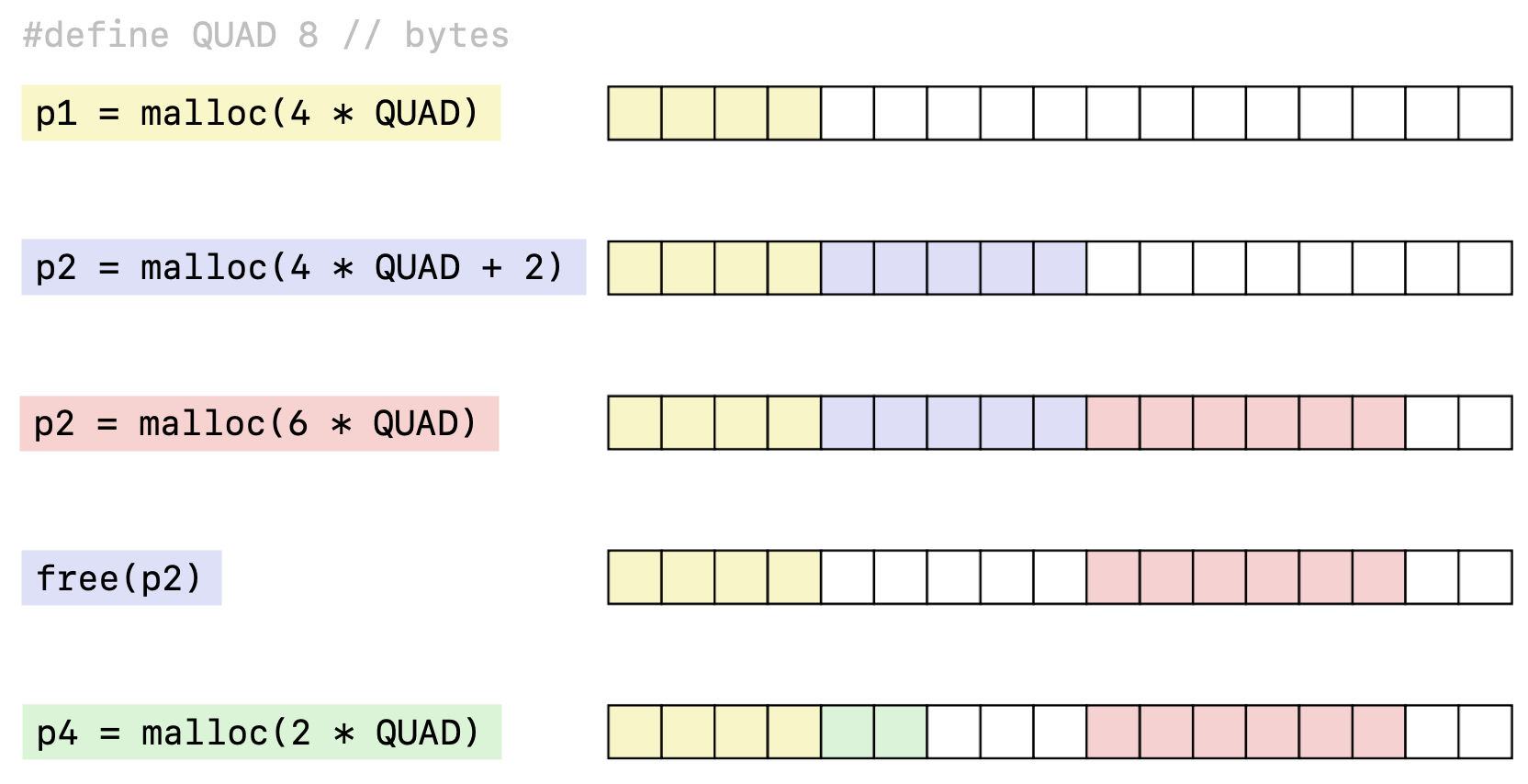

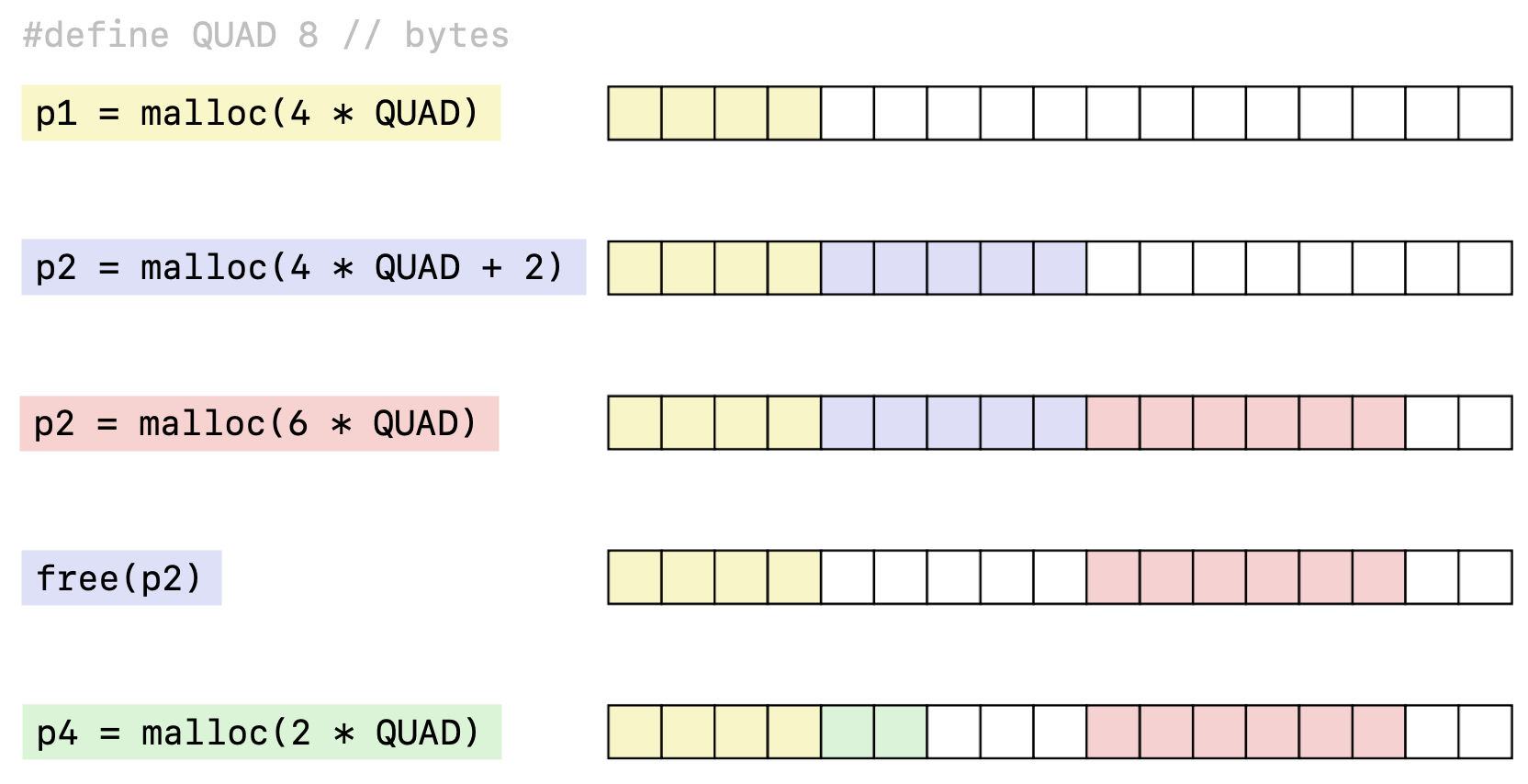

Consider the following allocation example:

Diagram taken from this link.

Diagram taken from this link.

This example illustrates the two types of memory fragmentation that can result in poor peak memory utilization. Put simply, fragmentation occurs whenever there is free memory in between two allocated memory chunks, because the presence of the free memory chunk fragments the contiguity of allocated memory. In this section, we’ll talk about each of these types of fragmentation.

Internal Fragmentation

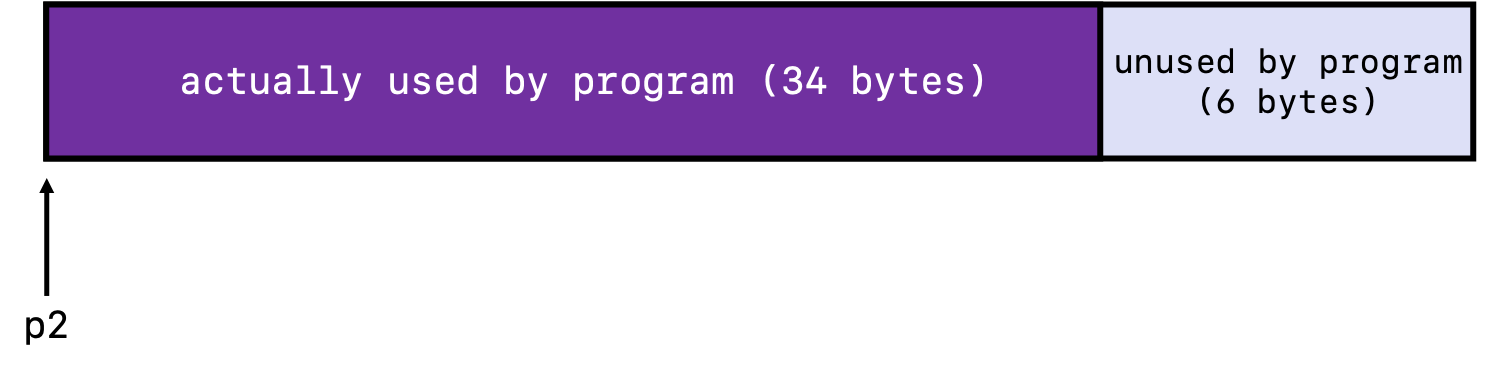

Consider the second malloc call for p2 from the example above:

void *p2 = malloc(4 * QUAD + 2);

Based on the malloc() argument, we only needed 34 bytes of memory, but the allocator gave us 40 bytes based on the diagram. This is because the allocator cannot give us a “fractional” memory block, because everything must be 8-byte aligned. In other words memory chunks can only come allocated in integer multiples of 8 bytes.

What happens as a result? Let’s take a look at the allocated memory block more closely:

What is happening here is that in this case, padding for alignment purposes has resulted in internal fragmentation because the payload is smaller than the block size, and so there is a chunk of memory 6 bytes large that is being unused. Internal fragmentation can often be caused by:

- padding for alignment purposes (what we just discussed)

- overhead of maintaining heap data structures (to be discussed)

- explicit policy decisions (e.g. we might decide the minimum block size should be 16 bytes, and a user wants to

malloc()only a single byte)

Notice that internal fragmentation depends only on the pattern of the current and previous requests, and so this type of fragmentation is fairly easy to measure quantitatively.

External Fragmentation

Contrast to internal fragmentation is external fragmentation, which occurs when there is enough aggregate heap memory, but no single free block is large enough. For example, let’s go back to our previous color-coded malloc() diagram from above:

Diagram taken from this link.

Diagram taken from this link.

Imagine that after the last p4 malloc() call, we have the following memory allocation call:

void *p5 = malloc(4 * QUAD);

This means that we want our allocator to allocate to us a single chunk of memory that is 4 8-bytes large. We have 5 blocks of memory available and certainly have enough space available to satisfy this request, but the problem is that no single free chunk of memory is able satisfy this request, as the only two free chunks above have 3 blocks and 2 blocks, respectively. Because a malloc() call must return a pointer to a single, contiguous memory space, the request will fail. This is an example of external fragmentation.

Note that the extent of fragmentation depends on the pattern of future allocation and deallocation requests, and so this type of fragmentation is fairly difficult to measure. As we will see down the road, there is often a tradeoff between these two types of fragmentation.

Keeping Track of Free Blocks

An allocator must have some way to keep track of the free blocks still available to be allocated. There are a number of different ways to accomplish this, but we’ll discuss the two most basic methods here.

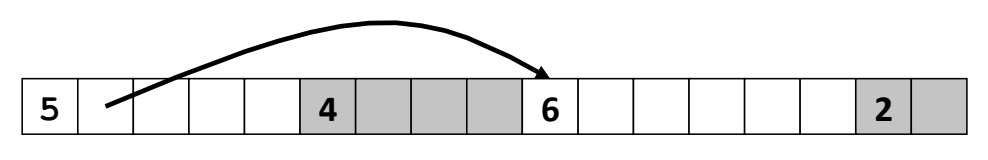

Implicit List

An implicit list works by storing the sizes of each of the chunks of memory in the first 8-byte block of the payload, which we’ll refer to as overhead storage. By knowing how large an allocated or free block is, we’re able to know how far to “jump” to get to the next chunk of memory.

In the overhead, we would also likely set aside a single bit to let us keep track of whether the memory block is allocated or not. Therefore, within a single quadword memory block, we could have a single “allocation flag” that is either 1 or 0 to keep track of whether the block is allocated, and the remaining 63 bits can be used to keep track of the size. Note that this overhead would increase the amount of implicit fragmentation since an 8-byte block will always be used to store information about the memory chunk and not to store a payload, but this is necessary in order for us to keep track of which blocks are free or not.

Explicit List

From above, implicit lists worked by allowing us to go through each of the memory chunks one by one and check if each was allocated or not. In contrast to this method, we can have an explicit list of free blocks, which essentially uses something analogous to a linked list to store the free blocks.

Now, our overhead for each block must include not only the size and allocation bits of the blocks, but also an additional 8 bytes that store a pointer to the next free block in the heap. Many common implementations of explicit lists also often store pointers to not only the next free block, but also the previous free block, effectively implementing a doubly linked list.

More Advanced Techniques

There are more advanced techniques to keep track of free blocks than implicit and explicit lists, but we will not discuss them here. Two of the most common ones are perhaps the segregated free list and sorting blocks based on size. For convenience, we will not discuss them here, but you are free to read about them at this link.

Free Block Search Algorithms

Implicit List

For implicit lists, there are three common ways to search through the heap to find the next free block.

- First Fit Algorithm: This method searches the heap from the beginning and finds the first free block that fits the requested size. It can often be fairly fast (especially compared to best fit), but can often cause a large amount of external fragmentation at the beginning of the list.

- Next Fit Algorithm: This method is similar to first fit, but instead of searching the heap from the beginning, it starts searching from where the previous search finished. This is probably the fastest of the three methods because it avoids re-scanning unhelpful blocks, but coincidentally, some research actually suggests that its fragmentation is the worse out of the three algorithms.

- Best Fit Algorithm: This method choices the best free block, which is simply an unallocated block with the fewest bytes left over that still fits the requested size. Because of the optimal fit, this method keeps fragmentation minimal, but it will typically run much slower than the other two methods because you must search through the entire heap every time in order to determine the “best fit.”

As you can see based on these three algorithms, there is often a trade-off between peak memory utilization (space efficiency) and throughput (time efficiency). This makes choosing an “optimal” malloc() implementation often very difficult.

Explicit List

Recall from above that an explicit list involves creating a linked list of the free blocks. We have different options in choosing an insertion policy for implementing the explicit list. That is, when we have a newly freed block due to calling free(), where do we insert this newly freed block in our linked list? There are two common options:

- LIFO Insertion Policy: Insert the freed block at the beginning of the linked list. The benefit is that this algorithm is quite simple to implement and is constant time. However, one downside is that some studies have suggested that external fragmentation is worse than address-ordered insertion policy (discussed below).

- Address-Ordered Insertion Policy: Insert freed blocks so that the free list blocks are always in increasing address order. That is, the order of the linked list is the same as the order of the physical freed blocks in memory. The benefit is that some studies have suggested that there is less external fragmentation when compared to a LIFO insertion policy (discussed above). However, one downside is that it requires a linear-time search to know where to insert the freed block when calling

free(), which will be slower than a constant-time implementation.

Technically speaking, you could also have first, next, and best fit algorithms as well using the explicit free list, but first fit is probably the most common algorithm when implementing the free list.

Splitting and Coalescing

sbrk()

Try It!