Intel x86 Computer Architecture

What is Assembly Language?

Assembly language is perhaps one of the most low-level programming languages out there. It involves writing instructions for exactly how variables and data types are stored and manipulated by the computer’s central processing unit (CPU), which can be thought of as the “brain” of a computer that executes computer instructions.

Just as each person’s brain is hardwired differently and understands things differently, each CPU processor understands a different assembly language. For example, the class of languages understood by smart phones, which are often referred to as RISCs (reduced instruction set computers) is very different than the class of languages understood by most modern computers, often referred to as CISCs (complex instruction set computers). The actual differences between RISCs and CISCs are not super important for our discussion, but in general, RISCs are more efficient but often have less “words” or commands in their language, while CISCs are more complex and have many more commands in their language.

x86 is one of the most common CPU’s in the market today, and were all based on the first-generation 8086 and 8088 CPU’s released in the late twentieth century. Of course, x86 has its own assembly languages that it uses to understand and run instructions. The reason why x86 assembly language is particular interesting for us to study is that virtually all modern computers have x86 CPUs. In my experiences, I have never come across a single computer that doesn’t run x86. Because it is so omnipresent, we will focus our discussion in understanding x86.

Why is Assembly Language Important?

The vast majority of computer programmers will learn about assembly language once and then never touch it ever again. After all, why would anyone want to learn an arguably complex and difficult to debug language like x86 assembly as opposed to using languages like Python and Java instead? In fact, there are a number of reasons of why every programmer should have at least a basic understanding of assembly language:

- Understand Computer Architecture: Understanding and writing assembly language code requires you to have a rigorous understanding of the architecture and hardware inside a computer. Having a solid understanding of computer architecture can allow you to write more efficient code and faster algorithms, even in languages such as Java and Python.

- Understanding Compiler Optimizations: It turns out that the code that we write everyday in Java, Python, and other introductory languages can often be very slow if the computer executed it as is. Therefore, when your computer is translating the code that you write into machine instructions that can actually be executed, it often makes optimizations to make the translated machine instructions run faster. We saw a couple of examples of this when we discussed bitwise operations, where we explored how the

XORbitwise operator could be used to swap variables instead of using a temporary third variable. Compilers often make many of these optimizations, and it is sometimes important to understand how these optimizations affect the performance of your code on different machines. - Completely Controlling Computer Resources: We mentioned it previously, but assembly language programs and C programs are faster and more efficient than programs written in “higher-level” languages such as Python or Java. Assembly language is the gateway to optimization in speed because it doesn’t involve any unnecessary infrastructure or background operations.

Given these important reasons to understand assembly, let’s look at some of the important features of the x86 assembly language.

One Note Before We Get Started

For some reason, there are two “dialects” when it comes to x86 assembly language: the Intel dialect and the AT&T dialect. In general, the Intel syntax is typically used on Windows machines, while the AT&T syntax is typically used on Unix systems, which includes Mac and Linux OS. Because we’re exclusively using Linux (or at least Unix) systems to learn about computer systems, all of our work in x86 will be in AT&T syntax.

The Basics of Computer Architecture

Computers have multiple components to them, including the CPU, primary storage (RAM), and secondary storage (SSD). Each of these serve different purposes:

- Computer programs and data are typically stored on secondary storage, which are things like hard drives and solid state drives (SSD). Secondary storages are meant for retaining data for a long period of time, even after the computer is turned off or the power plug is pulled.

- When a program needs to be executed, it is copied from the secondary storage into the main memory, also referred to as the primary storage. This is often referred to as the random access memory (RAM). Information stored on the RAM is for the CPU to directly interact and work with. Primary storages are meant to temporarily work with data, and information stored on these devices are lost when the computer is turned off or when the power plug is pulled.

- As we have discussed earlier, central processing units (CPUs) directly interact with the primary storage in order to carry out machine instructions and perform various computations.

Of course, the picture gets a lot more complicated than this, but for now, this is the lowest level of abstraction that we need for our purposes.

Primary Storage Memory: Stacks and Heaps

Pointers are a crucial aspect of the CPU being able to understand where things are stored in primary storage. The RAM of computers is often divided up into two sections: the stack and the heap. In terms of ADTs, the stack can be represented as a stack, while the heap can better be through of a list. However, in both cases, the elements of both the stack and the heap do not have to be restricted to a certain size value. There are a number of differences between the stack and the heap:

| Stack | Heap | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| stores local variables | high-speed access | fairly limited memory size | contiguous memory in LIFO order | variables cannot be resized |

| stores global variables | slow access speeds | large memory size | memory stored in random order | variables can be resized |

There are number of other differences, but these are the main differences. An image of what the primary storage memory can be found here, but basically, the main idea is that the stack and the heap do different things and serve different purposes. (I found the link particularly informative in explaining the purpose of the stack in RAM.)

Pointers

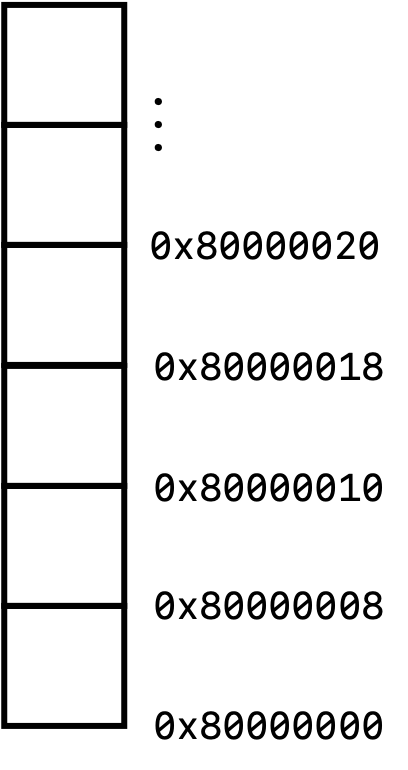

Pointers are essentially addresses to locations in memory, and tell us the location of where things are stored in the primary storage. We briefly introduced the topic of pointers at the very beginning. Let’s focus on how pointers are used to represent locations in the heap, which is typically what we are most interested in:

On 64-bit computers (that is, most modern computers), we say that the heap is 8-byte aligned. This means that each “chunk” of memory a multiple of 8 bytes. (On older 32-bit computers, the heap is 4-byte aligned). We can think of each of this little squares as houses with their own individual addresses, given by the 0x8000xxxx` addresses shown in the figure above.

In x86 assembly language, we have a very particular method of referring to the contents of each of these addresses:

- A plain string refers to the actual contents at that particular address. For example, if the integer

3was stored at0x80000008, then writing code0x80000008refers to the contents stored at the address0x80000008, which in this case is3`. As we will see later on, there is a bit of nuances when referring to addresses in registers, but we’ll talk about it below. - A string with a

$dollar sign symbol in front refers to the actual string literal. For example, writing the code$0x80000008refers to the actual hexadecimal number80000008. - A string encased in

[]brackets means refers to the contents stored at the address at the address stored in our particular address. Let’s break this down, as this is an incredibly confusing statement. Imagine that we have the value0x8000000stored at the address0x80000010. In this case,[0x80000010]would ask us to take the value stored at0x80000010, which is0x80000000in this case, and treat this value itself as another memory address. We would then go to the memory address0x80000000, and[0x80000010]would then refer to whatever is stored there.

This might seem extremely confusing at first, but it will get simpler as we go over a couple of example exercises below.

The Basics

Variable Size Suffixes

Because x86 assembly works directly with the individual bits and bytes stored in memory, we are typically not interested in what the actual bits represent or what the variable type is at such a low level of programming. However, we do care about the size (number of bits) of the quantities that we are working with.

Let’s consider an example problem. Consider the case where we have an instruction that says “move $2 to 0x80000008.” Is this instruction moving the value 2 into the least significant byte at address 0x80000008? Or is it moving the 32-bit integer representation of 2 into the least significant 4 bytes at address 0x80000008? Since either of these is a valid possible interpretation, we usually have to explicitly declare which one we are intending. Therefore, we have the following size suffixes:

b: least significant 1 byte (stands forbyte)w: least significant 2 bytes (stands forword)l: least significant 4 bytes (stands forlong)q: all 8 bytes (stands forquad)

There are a couple of more advanced operation suffixes, such as s (stands for single) and t (stands for ten bytes), but they are typically rarely used (at least in basic x86 assembly code) and so we won’t really talk about them here. However, you’re free to look up what they mean online if you’re interested.

While it isn’t always explicitly necessary to declare the size suffix in every operation, it’s often good practice to make clear actually what the intent of your operation is and how many bytes you’re intending to work with in a given instruction.

Registers

There is one last (and extremely important) topic that we need to discuss before we can start reading and writing x86 assembly code: registers. Registers are essentially temporary memory storages that can be accessed extremely quickly by the computer, and are used by the CPU to directly make computations and what not.

On modern Intel 64-bit computers, there are sixteen different general-purpose registers, and each of them have their own purposes and “memory address” names. We’ll list the different names here:

| 64-bit register | lowest 32 bits | lowest 16 bits | lowest 8 bytes |

rax |

eax |

ax |

al |

rbx |

ebx |

bx |

bl |

rcx |

ecx |

cx |

cl |

rdx |

edx |

dx |

dl |

rsi |

esi |

si |

sil |

rdi |

edi |

di |

dil |

rbp |

ebp |

bp |

bpl |

rsp |

esp |

sp |

spl |

r8 |

r8d |

r8w |

r8b |

r9 |

r9d |

r9w |

r9b |

r10 |

r10d |

r10w |

r10b |

r11 |

r11d |

r11w |

r11b |

r12 |

r12d |

r12w |

r12b |

r13 |

r13d |

r13w |

r13b |

r14 |

r14d |

r14w |

r14b |

r15 |

r15d |

r15w |

r15b |

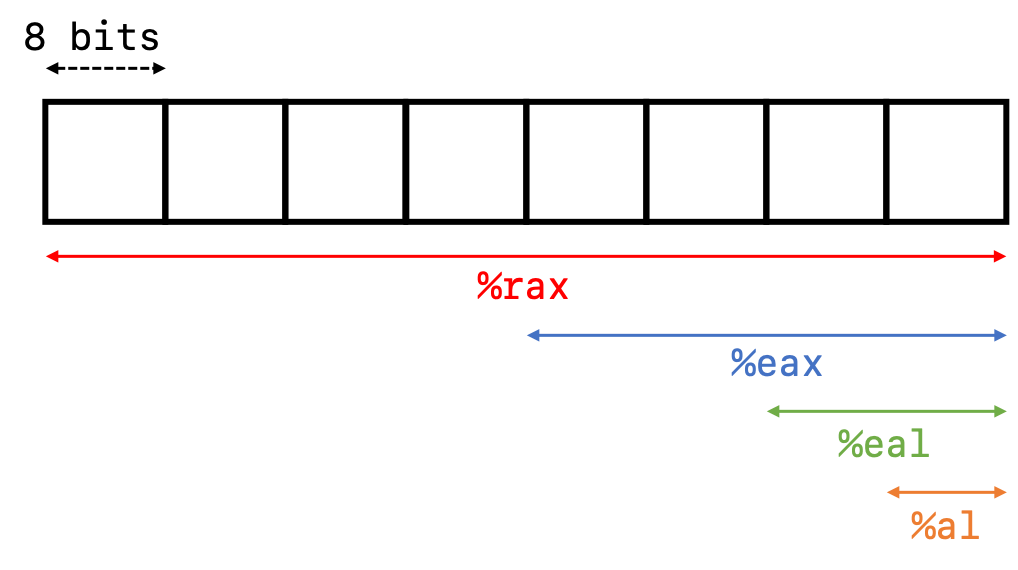

Here is a picture of what a typical register looks like and is subdivided into. The most significant bit is located on the left, and the least significant bit is located on the right.

As you can see from this diagram, all registers in x86 are prefaced in assembly code by a % sign. This is what indicates to the computer that we’re dealing with the contents within the register.

Now that we understand what computers look like “under the hood,” we can begin to investigate how to write instructions and manipulate memory and registers and whatnot in the next section.