Stacks and Queues

Previously, we discussed one of the many abstract data types in programming: lists. Lists had particular characteristics about them in that they could keep an ordered list of items, and we could insert and remove elements while still maintaining the order of the list. Today, we will be introducing two new types of ADTs: stacks and queues.

Stacks

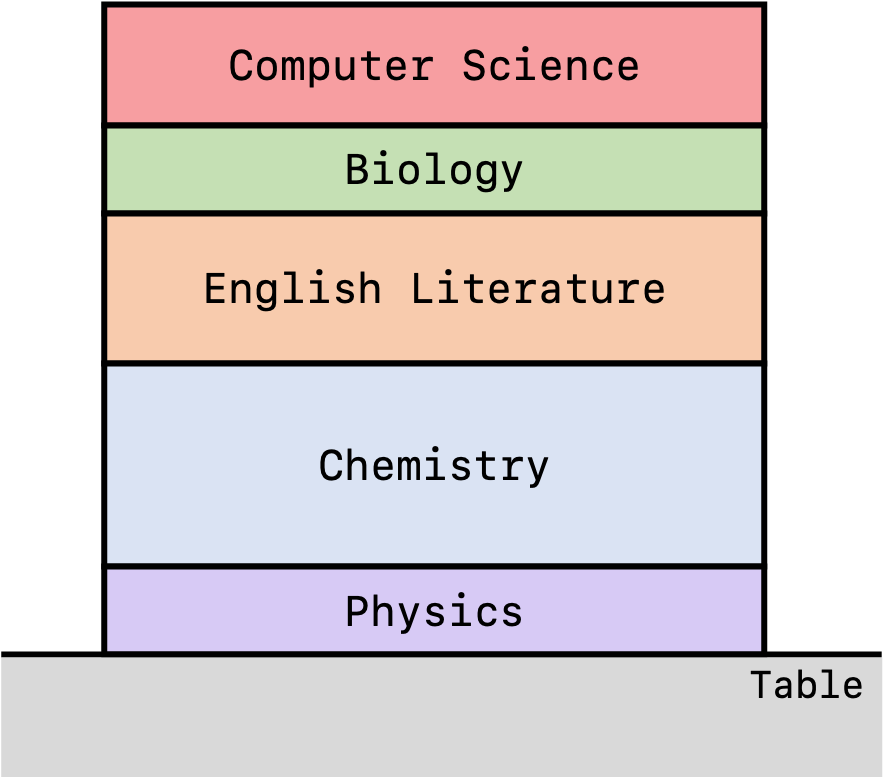

Imagine that you had a stack of extremely heavy textbooks for a variety of classes on your desk.

Because the books are so heavy, we’re only able to lift one book at a time. This means that if we wanted to add another textbook to the stack, say on American History, we wouldn’t be able to add it to anywhere except the top of the stack above the “Computer Science Textbook.” Similarly, if we wanted to remove the “Chemistry” textbook, we wouldn’t be able to do so unless we also removed the “Computer Science”, “Biology”, and “English Literature” textbooks first.

This feature about the stack of textbooks establishes a set of constraints on the order in which we can remove and add new textbooks. In creating this stack of textbooks, clearly “Physics” had to be placed on the table first, followed by “Chemistry” all the way up to “Computer Science.” If we wanted to then remove all of the textbooks from this stack, we would have to remove the “Computer Science” textbook first, followed by “Biology” and then all the way sequentially to “Physics.” In this example, “Computer Science” was the Last textbook to be placed In the stack, but the First textbook to be taken Out of the stack. For this reason, we refer to stacks as implementing a Last-In-First-Out (LIFO) policy. Note that this is a characteristic of all stacks.

From generalizing this example to apply to computer programming, we can think of the stack as an ADT where a particular order of similar objects is maintained, similar to a list. However, unlike a list, we cannot insert a new element just anywhere in the stack, or remove any element from anywhere in the stack. All stacks must obey the LIFO policy that the first item added to the stack must be the last item that is removed from the stack.

Important Methods of a Stack

There are key methods that are integral to the functionality of stacks:

boolean isEmpty() |

returns whether or not the stack is empty |

void push(Object o) |

adds or “pushes” an item onto the top of the stack |

Object pop() |

returns and removes or “pops” the item at the top of the stack, which was the item that was inserted most recently |

Object peek() |

returns or “peeks” at the item at the top of the stack, but doesn’t remove it |

int size() |

returns the number of items currently in the stack |

Of course, there are other methods that a stack can implement. For reference, the methods of the Java stack interface can be found in the appropriate documentation here.

Java Implementations of a Stack

When previously discussing the list interface, we also introduced two different implementations: the ArrayList and the LinkedList. They could do everything that a list should do, but the way that they accomplished this under the “hood of the computer” was different.

In Java, there are a number of classes that can implement the stack interface. One of them is, perhaps obviously, the Stack class:

public static void main(String[] args) {

// Creates a new stack of integers

Stack<Integer> myStack = new Stack<>();

// Pushes the integer 6 onto the stack

myStack.push(6);

// Pushes the integer -2 onto the top of the stack

myStack.push(-2);

// Will remove -2, the most recently added element, and print it.

System.out.println(myStack.pop());

// Will print out 6, but will not remove 6 from the stack

System.out.println(myStack.peek());

// Will return false, since 6 is still in the stack

System.out.println(myStack.isEmpty());

}

The full Java documentation for the Stack class can be found here. Another option for implementing the stack ADT is the Deque (pronounced “deck”) interface, which is a collection of different implementations including ArrayDeque, LinkedList, and others. Yes, the LinkedList we’re referring to here is the same LinkedList implementation that could implement the list interface as well! This tells us that a single implementation can implement different interfaces depending on the situation. For reference, I encourage you to check out the documentation here. For now, don’t worry about about the Deque for now. We will delve more in depth of what this is below.

Example of a Stack

In this section, we’ll walk through an example problem that would highly benefit from the use of a stack: the problem of determining whether a set of nested parenthesis is valid. We actually explored the same exact problem using recursion, but the bug in this problem is that if a set of parenthesis originally looked like ()(), then our function actually returned false, meaning that it wasn’t a correct nesting of parentheses. However, in this test case, it should have returned true. Unfortunately, there is no easily programmable solution to this bug. However, with our new knowledge of stacks, this problem can actually be pretty easily tackled. Let’s first restate the problem:

Given a String, return true if it is a nesting of zero or more pairs of parentheses, like (()) or ((())).

The idea is that we will go through the entirety of the String from the beginning (left) to end (right), and every time we see an open parenthesis (, we push onto the stack. Every time we see a closed parenthesis ), we pop off of the stack. If there are a “balanced” number of parenthesis, then the stack should be empty after way parse through the entire String. If we ever call pop() on an empty stack, then we know that a closed parenthesis came before an appropriate open parenthesis, and so there was not a balanced number of parenthesis. Our implementation might look something like this:

Make sure you understand the code and how it works. Noticed that we also used recursion in this example as well; if you’re unfamiliar with recursion, I would definitely recommend reading this page first. Feel free to play around with it as well! (It takes a couple seconds (about 15 seconds on my computer) for the program to run, so be patient.)

Queues

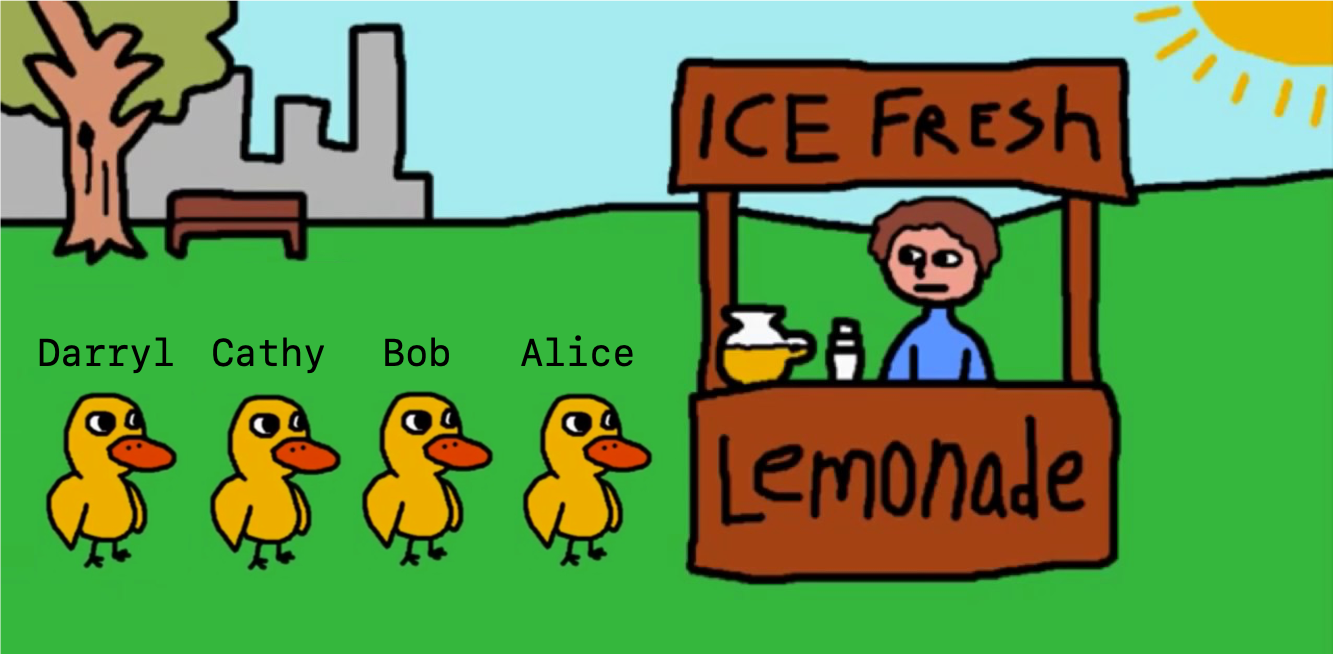

Now, let’s consider an entirely new, separate scenario now, where we can imagine that there is a group of ducks that are waiting in line to get lemonade (or maybe grapes).

Let’s think about the line of ducks that are waiting at the lemonade stand. From our experience, Alice was the first duck that entered the line and should be the first one that is served lemonade, whereas Darryl was the last duck the entered the queue should be at the very end of the line to be served lemonade. It’s not fair that if Alice arrived after Darryl that she should be in front of him in line, as that’s cutting the line. In other words, this line of ducks is implementing a first-in-first-out (FIFO) policy. This means that the First duck that enters Into the queue should be the First duck that exits Out of the queue.

Check Your Understanding: What would happen if the line of ducks was instead modeled as a stack using the LIFO policy? Does the resulting situation seem fair to you?

A list that implements a FIFO policy is called a queue. If you think of any line that you’ve had to wait in: the school lunch line, waiting in line for tickets to a movie, or the line the ride the new rollercoaster at the county fair. All of these are examples of a collection of objects (or people) that can be modeled well by a queue ADT.

Important Methods of a Queue

Just as there were characteristic methods of a stack from above, where are also key methods that are integral to the functionality of queues:

boolean isEmpty() |

returns whether or not the queue is empty |

boolean offer(Object o) |

queues the object at the end of the queue and returns true if the task is successful; otherwise, it returns false |

Object peek() |

returns the head of the queue, and returns null if the queue is empty |

Object poll() |

dequeues and returns the head of the queue, and returns null if the queue is empty |

int size() |

returns the number of items currently in the queue |

Terminology: To add an element to the end of the queue is to enqueue the element. To remove an element from the beginning of the queue is to dequeue the element.

Java Implementations of a Queue

There are many different Java implementations of a queue, all of which are listed in the current Java documentation linked here. Perhaps the most common implementations are ArrayDeque, LinkedList, and something called a PriorityQueue. The concept of a “priority queue” is a much more advanced topic that we will talk about more in detail later. One example of how a queue looks like within a real Java program is this:

public static void main(String[] args) {

// Creates a new queue of integers

Queue<Integer> myQueue = new ArrayDeque<>();

// Queue the integer 6 in the queue

myQueue.offer(6);

// Queue the integer -2 in the queue

myQueue.offer(-2);

// Will remove 6, the least recently added element, and print it.

System.out.println(myQueue.poll());

// Will print out -2, but will not remove -2 from the stack

System.out.println(myQueue.peek());

// Will print out false, since -2 is still in the stack

System.out.println(myQueue.isEmpty());

}

Example of a Queue

Queues have many different uses in a variety of algorithms. The main applications of queues are when we’re trying to search particular data sets, such as processes called traversing a binary tree and breadth-first search (BFS) algorithms. Unfortunately, these processes are far beyond the scope of our discussion in involve introducing some very advanced programming techniques that won’t be discussed until much, much later down the road. Instead, in this example, we’ll go over just one of the simple examples of how to use a queue in Java programming practice.

Print out the first $N$ numbers of the following sequence of numbers: 1 10 11 100 101 110 111 1000 1001 1010 1011 1100 1101 1110 1111 10000 ....

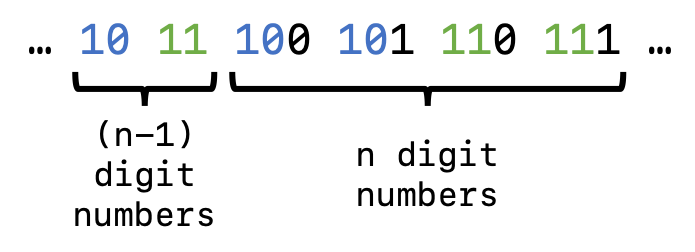

Our first task is to determine what the pattern is in this sequence. It might be difficult to see this, but every time the number of digits increases from $n-1$ to $n$, the sequence continues by taking the sequence of $n-1$ digit numbers and appending 0 and 1 to the end to get the $n$ digit numbers. For example, in the case where $n=3$,

This suggests that we could establish a queue of numbers to print out. Every time we dequeue a number to print – say, the 10 in the example above – we enqueue two new numbers to print, which are made by appending a 0 and a 1 respectively to the end of the number we just dequeued. We continue this process until we’ve printed out the $N$ numbers. Now that we our algorithm outlined, let’s implement it in Java:

(Note that this program might take a while to run, so be patient with it!) You can try to change the number of printed elements by appropriately modifying the number in the main() function. (If you’re also familiar with binary numbers, this sequence of numbers is the binary representation of the first $N$ natural numbers.)

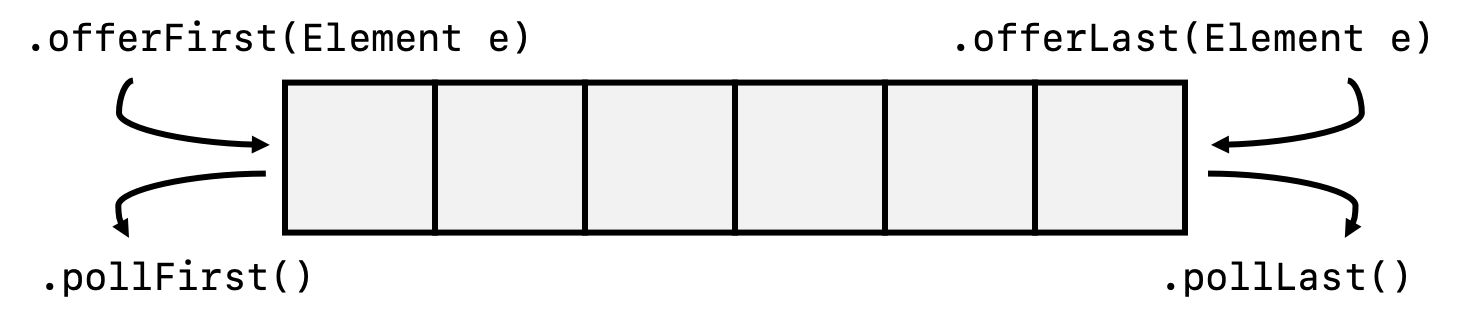

Deque

In talking about both stacks and queues from above, we introduced, without explanation, the Deque (again, pronounced “deck,” like a deck of cards). A deque is simply a Java data structure that allows you to enqueue and dequeue elements from either end of the deque. This is why it is called a deque, which stands for a “doubled ended queue.” It has more versatility/flexibility than both a stack or a queue, but because you cannot add or remove just any element from the middle of the deque, it is not simply a list. Imagine it as a hybrid combination of both a stack and a queue.

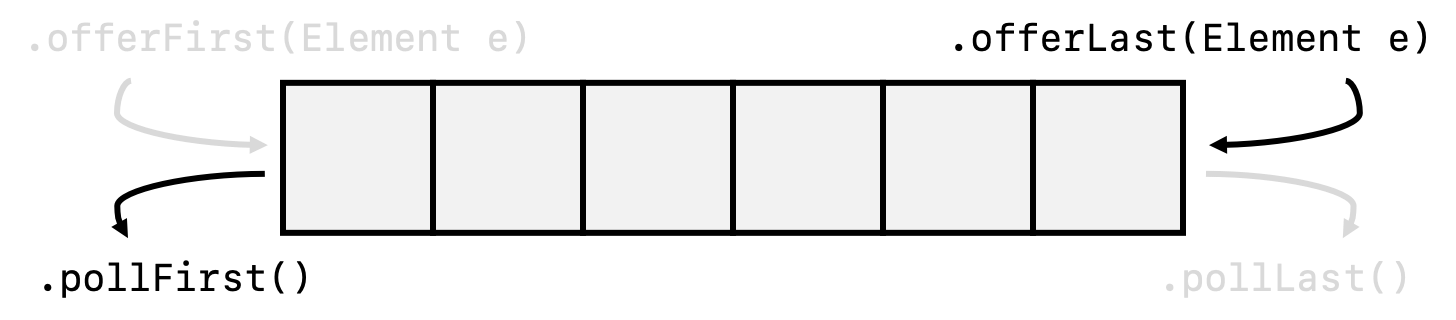

By restricting the options of how to add and remove elements, we can functionally achieve either a stack or a queue, depending on the desired purpose of the deque. For instance, a deque can implement a queue by restricting us to only use the .offerLast() and .pollFirst() functions, which are our enqueue and dequeue functions, respectively.

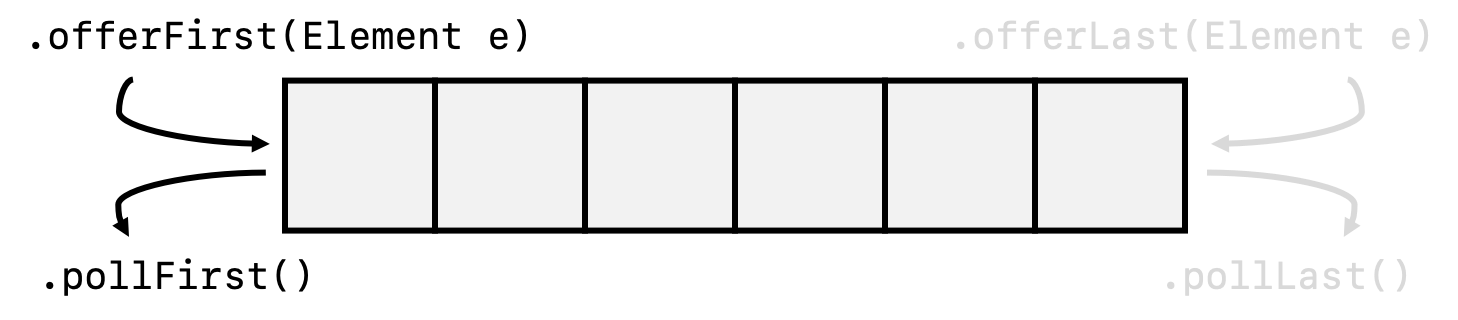

Similarly, a deque can implement a stack by restricting us to only use the .offerFirst() and .pollFirst() functions, which are our push and pop functions, respectively.

Because of the functionality of the deque, this particular data structure is perhaps one of the most popular implementations of both stacks and queues. As we’ve seen briefly in earlier examples above, one of the ways that we can restrict the functionality of the deque to act as either a stack or a queue is to simply declare the data type as either a stack or a queue (or a deque):

public static void main(String[] args) {

// Creates a queue of integers called q

Queue<Integer> q = new ArrayDeque<>();

// Creates a stack of integers called s

Deque<Integer> s = new ArrayDeque<>();

// Creates a deque of integers called d

Deque<Integer> d = new ArrayDeque<>();

}

You can find the full documentation of the Deque in Java in the official documentation here. Note that unfortunately, Java doesn’t allow for statements like Stack<Integer> s = new ArrayDeque<>(); because the ArrayDeque data structure doesn’t technically implement the stack interface in Java. Therefore, we would typically declare it as a Deque and then use the deque as an effective stack. Of course, another option is to avoid the use of deques entirely and use the Stack data structure from above, which again, would look something like

public static void main(String[] args) {

// Creates a stack of integers called s

Stack<Integer> s = new Stack<>();

}

Summary

Stacks implement a LIFO policy, meaning that the last element pushed onto the stack is the first element that is popped off of the stack. Queues implement a FIFO policy, meaning that the first element that enters the queue is the first element that exits the queue. Deques are “double-ended queues that can act as either a stack or a queue.

Addendum: The Use of Stacks in Recursion

In this last section, we’ll be giving a high-level, qualitative overview of how stacks fit into the bigger picture of recursion, which we discussed in detail last time. It is important to note that all of the material in this section is completely optional and should be read solely out of interest.

Let’s think back to the first example we ever discussed using recursion: calculating the factorial of a natural number $n!$, as discussed here. Our recursive function ultimately looked something like this:

public int factorial(int n) {

if (n <= 1) { return 1; }

return n * factorial(n - 1);

}

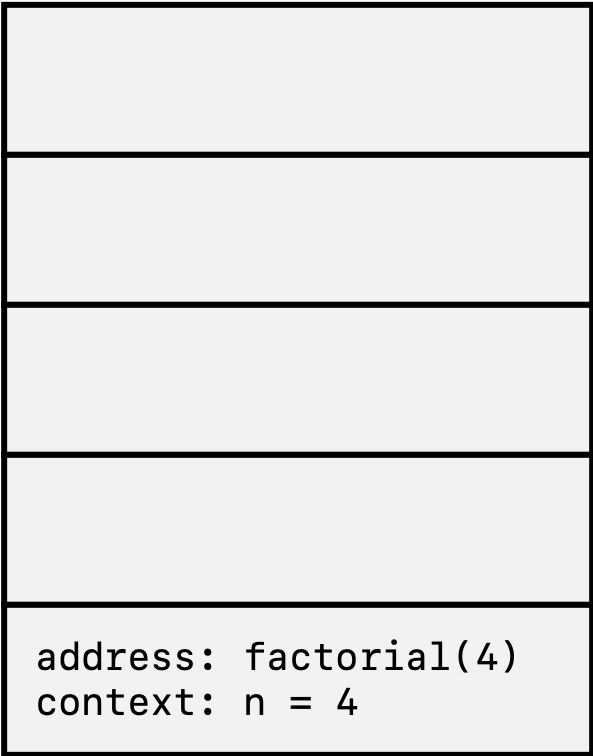

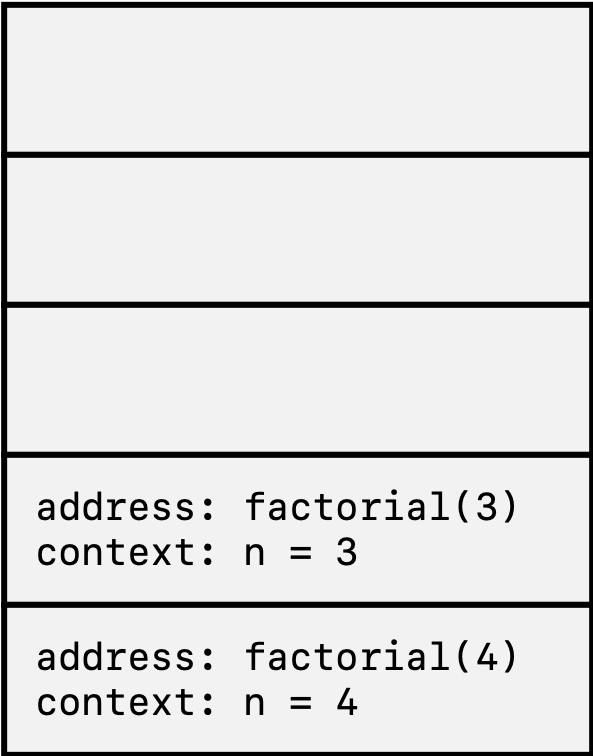

Let’s assume that we were trying to calculate the value of $4!$ using this function. All recursive methods make use of the memory stack that is present in all computers. This particular stack is particularly dedicated to allowing your computer perform particular operations. In this case, the stack will be used to allow us to execute a recursive function call.

What happens is that when the function is first entered, the value of $n$ is equal to 4. When we first get to the initial return statement, the function must enter into itself once more. However, before this occurs, the computer pushes the current value of $n$ and what we call the “address” of the function on the computer’s dedicated memory stack. The function address can be though of as the particular place in your computer’s memory where the function was being evaluated – similar to the home address of where you live. The current value of $n$ composes what we call the context of the function, which is essentially the variable values and state of the computer at the time that the recursive call was made.

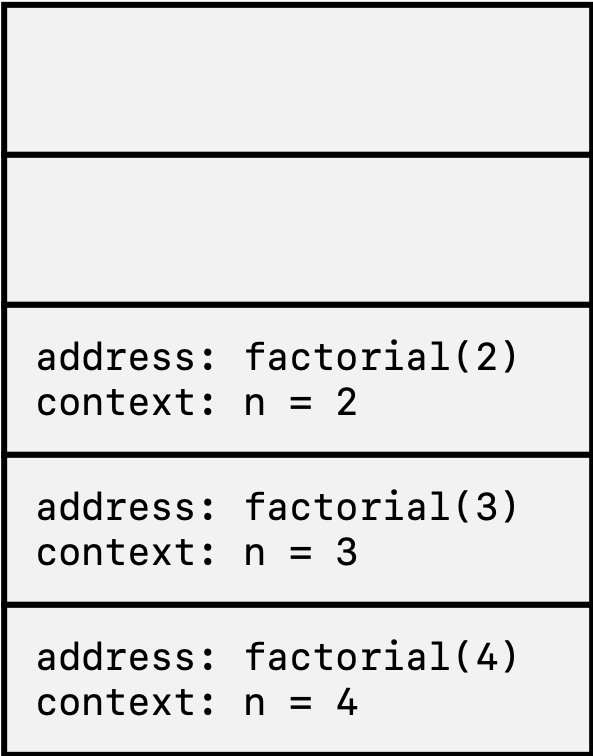

Of course, this process is repeated to push the address and context of the other recursive factorial() function calls as well, each time storing the unique address of the function and context of the computer:

When the stack is in this state, this means that the computer is currently executing the function call factorial(1). In this case, the if statement tells us that rather than making another recursive function call, we should return the value of 1 instead. When this happens, the top of the stack is popped to restore the most recent context of the computer ($n=2$) and also tell us to return to the function factorial(2), now knowing that factorial(1)=1. At this point, the function can now conclude that factorial(2)=2*factorial(1)=2*1=1, and the state of the stack now looks like

We can repeat this process by restoring the next popped context and function address and so on until there are no more function address to pop and the stack is empty. At this point, we can return the value of factorial(4)=24. As we can see, the stack is a very useful data structure that is critical to allow computers to execute recursive function calls.

StackOverflowErrors

Let’s modify our factorial code from above slightly:

public int factorial(int n) {

return n * factorial(n - 1);

}

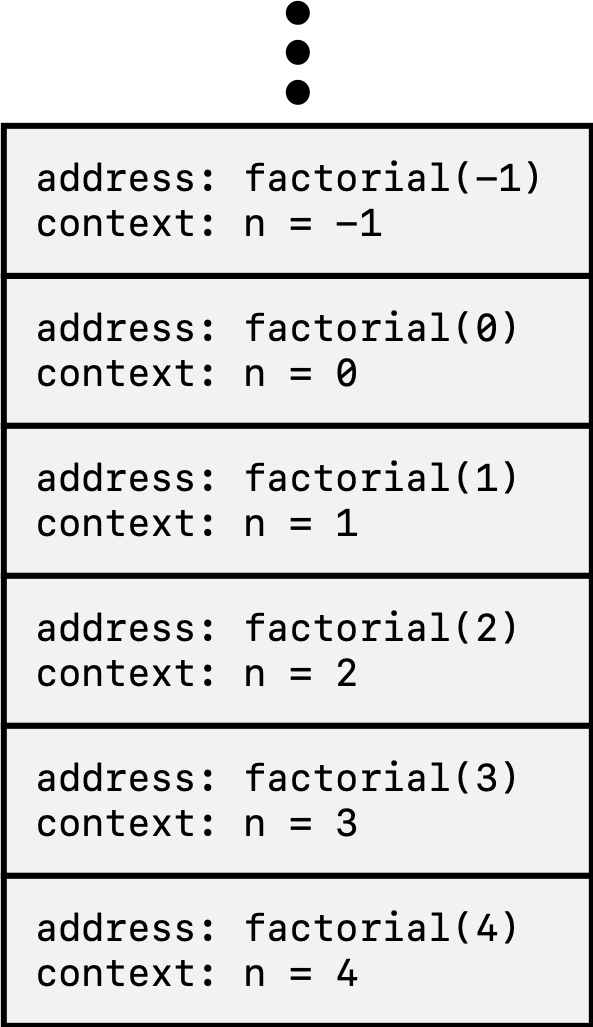

We have essentially removed the base case telling us to return 1 if n is less than or equal to 1. In this case, the recursive calls will never stop and function addresses and computer contexts will continue to fill up the rest of your computer’s stack:

There is no way to inform the program to stop making recursive calls, and so eventually, since your computer has a finite amount of resources and hence a finite stack size, you might imagine that too many things will get pushed onto the stack and there will be no more room to push anything else. In other words, the stack has overflown and the program must be terminated because the computer was unable to fully execute the entire program without first exhausting the computer’s resources. In this case, this is what leads to a StackOverflowError that you see appear often in many buggy recursive function calls.

Exercises

Problem 1

This problem is adapted from the introductory CS course at Princeton.

- Without actually running the program, what does the following code fragment do?

IntQueue q = new IntQueue(); q.enqueue(0); q.enqueue(1); for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) { int a = q.dequeue(); int b = q.dequeue(); q.enqueue(b); q.enqueue(a + b); System.out.println(a); } - What abstract data type would you choose to implement an “Undo” feature in a word processor (like Microsoft Word)?

Problem 2

Write a filter method reverse() that reads Strings one at a time and prints them to standard output in reverse order. For example, fox should return fox and The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog should return dog lazy the over jumped fox brown quick The. Is a stack or a queue most appropriate to use in this problem?

Problem 3

In the example above, we determined a valid method of using both stacks and recursion together in order to determine whether we had a valid combination of nested parentheses. However, there are other types of grouping symbols too: namely, the square brackets [] and the curved brackets {}. We might want to determine if a combination of parentheses, square brackets, and curve brackets are correctly nested. For example,

[(abc)]{}{[(x)()](2)} |

true |

[(]) |

false |

Write a Java program that accomplishes this task. (You can choose to use recursion if you’d like, but it is not necessary.)

Problem 4

The two fundamental methods of the stack interface are push() and pop(). It is possible to write a queue implementation of a stack interface that implements both of these methods. A rough idea is as follows:

Queue<Element> q = new Queue<>();

public void push(Element e) {

// Enqueue the element e

// For all of the elements currently in the queue except for e,

// dequeue and then queue again one by one.

}

public Element pop() {

// Dequeue the head of the queue.

}

- Make sure you understand why these

push()andpop()methods would work for a queue to implement the stack interface. (I highly recommend drawing a picture.) - Implement the three methods in the code segment in

MyStack.javabelow. The onlyArrayDequemethods that you may use aresize(),peek(),poll(), andadd(). If these methods are unfamiliar, make sure to read the relevant sections of the Java documentation forArrayDeques here. - Can a single stack be used to implement a queue interface? Explain why or why not.

- Can two stacks be used together to implement a queue interface? Explain why or why not.