Binary Search

Last time, we learned about recursion, which we introduced as a powerful programming technique where the function calls itself. In this lesson, we’ll learn about one of the most commonly tested and referenced algorithms that relies on the use of recursion. This algorithm is called binary search.

The Setup

Imagine that we have a sorted list of elements. For example, we could have a sorted list of integers:

Again, note that the list elements are sorted in increasing order. The fact that the list is sorted is very important (we’ll discuss why this is below).

Our problem statement is that we want to search for whether a particular element (integer) is in this sorted list. Using our current programming methods available to us, our most promising method would probably be to iterate over every single element in the list and check if it is equal to the element that we’re searching for.

/*

* Searches list for element, and returns the index of

* the element if found. Otherwise, returns -1.

*/

public static int linearSearch(int[] list, int element) {

for (int i = 0; i < list.length; i++) {

if (list[i] == element) { return i; }

}

return -1;

}

This is a completely valid way of searching for a particular element. We call this method of searching linear search. Unfortunately, it turns out that this method is pretty slow and will take computers a long time to run, especially when there are a lot of elements present in the list. It also doesn’t take advantage of the fact that the elements of the list are sorted. We want to determine a potentially faster method of searching that takes advantage of the fact that the list is sorted: this method is called binary search.

Binary Search

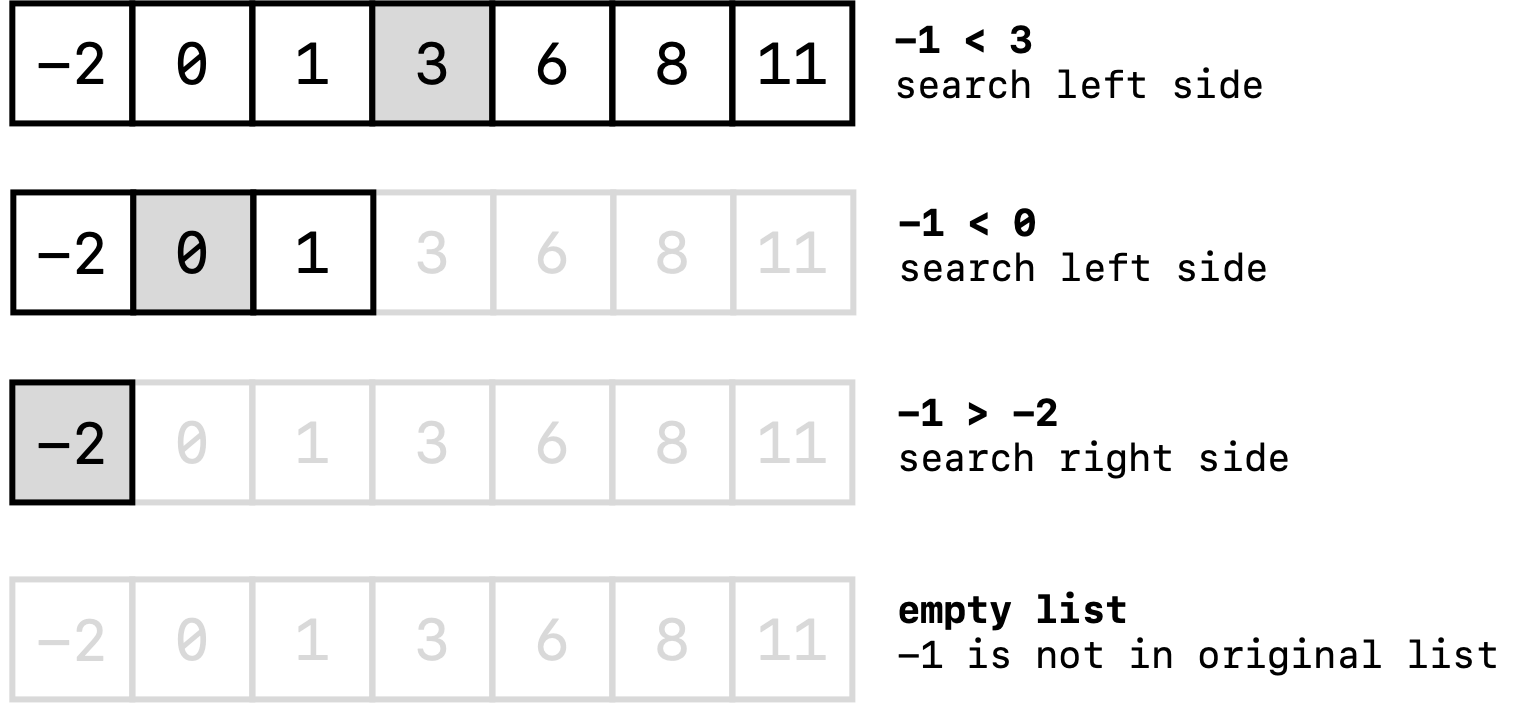

The idea behind the binary search is that we can first divide the array into two halves, and compare the element we’re searching for (call it $x$) with the element in the middle (call it $m$) that divides the two halves of the array. Since the array is sorted, we know that if $x>m$, then we only need to continue searching in the right half of the original array because the list is given to be sorted. If $x< m$, then we only need to continue searching in the left half of the original array. We can recursively continue this process until either the value is found, or if the interval is empty (meaning that $x$ was not in our original array. For example, let’s say that we were searching for whether -1 was in the array shown above. A visual diagram of how binary search would work is

From this binary search algorithm, we’ve determined that -1 is not in our list, and have used the fact that the list is sorted in order to continuously restrict the the space that we have to search. Here is an example of how to implement this algorithm in Java:

/*

* Searches list for element, and returns the index of

* the element if found. Otherwise, returns -1.

*/

public static int binarySearch(int[] list, int element) {

return binSearch(list, element, 0, list.length - 1);

}

/*

* Helper method to search the list for the element and returns

* the index of the element if found. Otherwise, returns -1.

* l is the index of the leftmost element of the (sub)array we're

* searching, and r is the index of the rightmost element of

* the (sub)array we're searching.

*/

private static int binSearch(int[] list, int element, int l, int r) {

// If the right index of the subarray is less than the

// left index, then we have an empty array, and so the element

// is definitely not in our array. This is one of the base cases.

if (r < l) { return -1; }

// Find the index of the midpoint element that divides the

// array in half.

int mid = l + (r - l) / 2;

// If the element that we're looking for is list[mid], then

// we can simply return mid! (This is the other base case.)

if (list[mid] == element) { return mid; }

// Otherwise, handle the other two possible cases recursively

else if (list[mid] > element) {

return binSearch(list, element, l, mid - 1);

}

else {

return binSearch(list, element, mid + 1, r);

}

}

Notice that our public method, binarySearch(), calls a private helper method called binSearch() in order to perform the actual algorithm. In a way, the private method is the one that is actually doing all of the calculations, while the public method isn’t really doing anything except act as a “shell” around the private method, so that other Java programs can call and interact with this method. This function architecture is quite common in many Java functions (especially recursive functions), and is called a public-private pair.

Recursive Public-Private Pairs

The main benefit of the public-private pair is that we are free to modify the parameters passed into the function to be different than the ones that the Java program actually wants to give. For example, the public method binarySearch() from above only requires the user to pass in the array and the element we’re looking for. They don’t also need to pass in the left and right indices that define the boundaries of the array. However, the left and right indices are crucial for us to perform the recursive steps. By separating out the function into a pair of methods, we can abstract away the unnecessary variables from the user’s perspective and just keep them in the private method.

In a public-private pair, we have a public, non-recursive method that only includes the parameters that the client really wants, and a private, recursive method that includes the all the parameters that we need for recursion.

Sorting Non-Integers: Lexicographic Sorting

For integers, it is fairly easy to know what it means to “sort” elements. This is because there is a standard definition of what integers are greater than, less than, and equal to other integers.

This introduces an important concept: in order to use the binary search algorithm, the elements of the array must be sorted. In order for the elements in the array to be sorted, we must have some sort of reasonable definition in order to compare two different objects in the list.

One example is for when we’re sorting Strings. In order to sort different Strings, one way to sort them is through sorting them the way that dictionaries sort them in alphabetical order. We refer to this as lexicographical sorting.

For things other than Strings and integers, the way to sort objects might not be intuitive. If you want to use binary search on a list of arbitrary objects, you often have to define a int compareTo() function in order to be able to realistically compare two objects. For example, the Java String object already has a pre-defined compareTo() function that sort items in lexicographical (alphabetical) order.

public static void main(String[] args) {

String a = "Alice";

String b = "Bob";

System.out.println(a.compareTo(b));

// This prints out a negative number because "Alice" comes

// before "Bob" in the dictionary

System.out.println(b.compareTo(a));

// This prints out a positive number because "Bob" comes

// after "Alice" in the dictionary

System.out.println(a.compareTo(a));

// This prints out 0 because "Alice" equals

// "Alice" in the dictionary

}

You can read more about the specifics of the compareTo() function specifically for Strings here. For other objects, you would have to define the appropriate int compareTo() function for the particular application. You can see some examples of implementing compareTo() functions here.

Sorting Arrays

We’ve seen how binary search is a much more efficient method of sorting arrays, but getting an array to be sorted in the first place is not a trivial task. Only an extremely small proportion of arrays are even sorted in the first place. Down the road, we will be discussing different algorithms on how to actually sort the arrays in the first place in order to do binary search (or any type of searching algorithm), which is a fairly complicated task.

More Complicated Search Algorithms

Essentially all commonly used search algorithms for finding a particular element in a list involve some sophisticated combination of using linear search and/or binary search. Without delving into too much detail, here are a couple of more advanced search algorithms (again, that only work on arrays that are sorted):

Jump Search

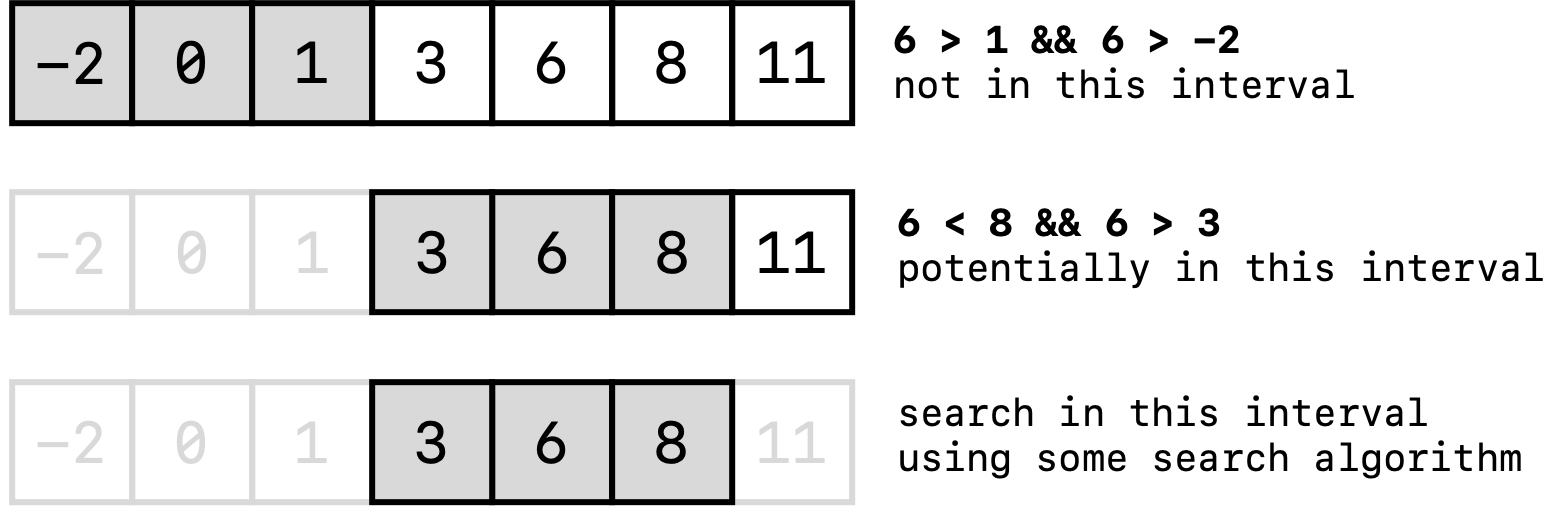

Assuming that the array is sorted, jump between intervals of some size $n$ elements until you find the interval where the desired element should be found. Then, use either linear or binary (or another jump search between intervals of size $m<n$) search to look within the particular interval.

For example, let’s say that we were searching for the element 6 in the following array of integers. A jump search with $n=3$ might look something like

GeeksforGeeks has an excellent article on jump search, and I invite you to check it out if you’re interested.

Exponential Search

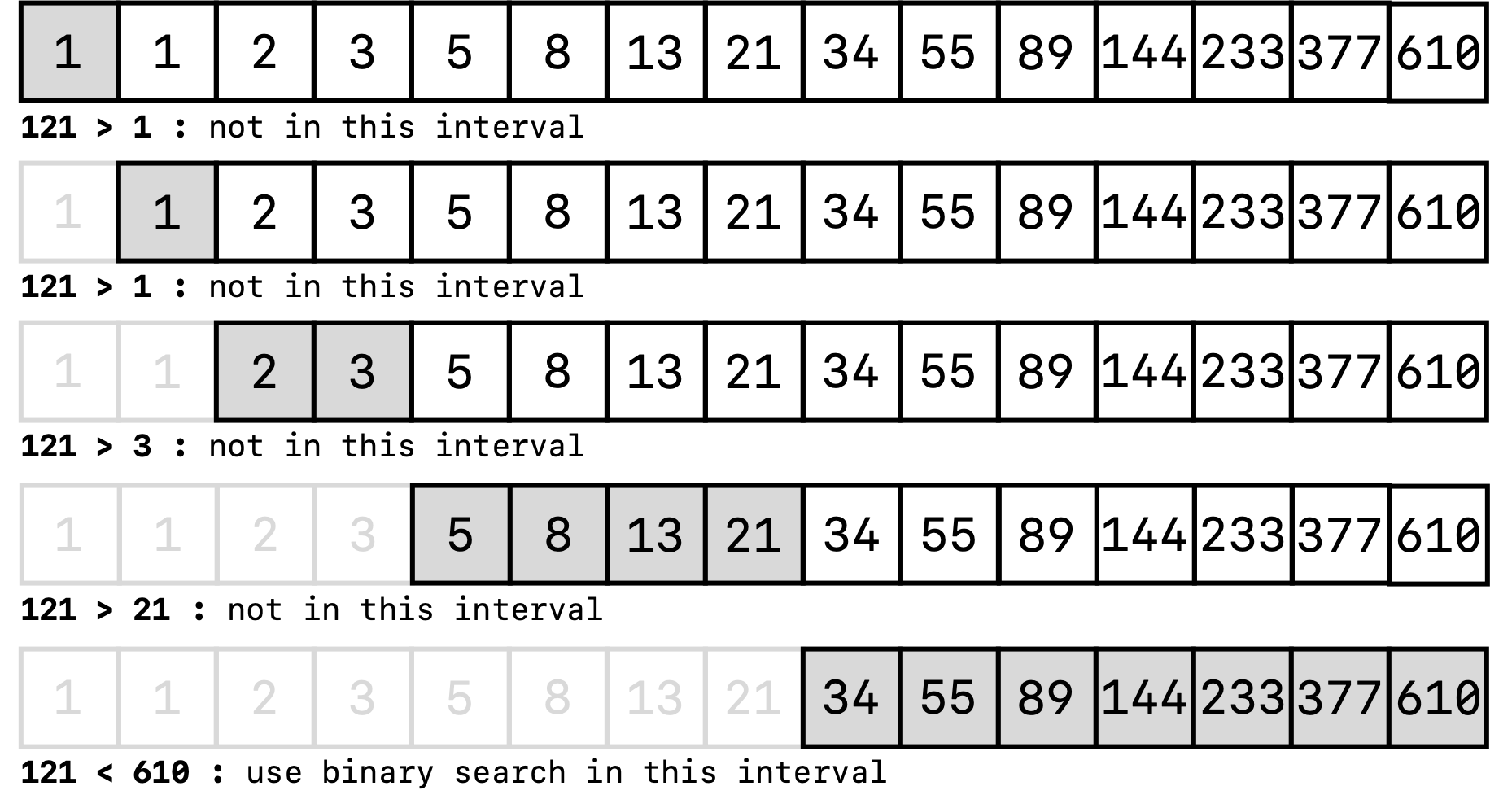

Assuming that the array is sorted, find the range where the element is present and then using binary search to look within the particular interval. The range that we look in should expand exponentially, typically from the first element, to the first two elements, to the first four elements, and so on. For example, let’s say that we were looking for the element 121 in the following array of integers. A standard exponential search might look something like

As we can see, exponential search is essentially the same thing as jump search, with the caveat that the search interval is not constant in size. Without proving this statement, the benefit of this search method is that it can efficiently search for elements in unbounded arrays where the size of the array is unknown. It is also more efficient in cases where we expect the element we’re looking for to be near the beginning of the array. Of course, you can also do a similar exponential search starting from the end of the array if you expect the element that you’re looking for to be near the end of the array.

Fibonacci Search

This search algorithm has essentially the same flavor as jump search and exponential search, except that instead of have a constant-size search interval (jump search) or an exponentially doubling search interval size (exponential search), the interval search size increases by the Fibonacci numbers.

| Search Iteration Number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | $\cdots$ |

| Search Algorithm Interval Size | |||||||||

| Jump Search | $n$ | $n$ | $n$ | $n$ | $n$ | $n$ | $n$ | $n$ | $\cdots$ |

| Exponential Search | $1$ | $2$ | $4$ | $8$ | $16$ | $32$ | $64$ | $128$ | $\cdots$ |

| Fibonacci Search | $1$ | $2$ | $3$ | $5$ | $8$ | $13$ | $21$ | $34$ | $\cdots$ |

Here, $n$ can be any positive number.

$n$-ary Search

In this lesson, we introduced the concept of the binary search, where we recursively divided our search interval into two smaller subintervals. However, we don’t need to necessarily divide the search integral into only two subintervals. We could just as easily have subdivided into three intervals, or four intervals, or $n$ intervals.

It turns out that in the slowest possible case, an $n$-ary search is slower than a binary search for $n>2$. We won’t delve into the mathematics of how to prove this, but our choice to use binary search instead of $n$-ary search arises simply because it’s faster to use binary search.

Exercises

Problem 1

In this program, we will compare the speed of binary search vs. linear search. Let’s write a program to give us an idea of how much faster binary search can be when compared to linear search. Run the following program to compare the behavior of binary search vs. linear search for different sizes arrays to search through. What do you notice? Note: I would recommend running the program multiple times to try to get somewhat consistent results.

Problem 2

This question commonly comes up in software engineering job interviews at Facebook, Amazon, and Microsoft.

Using a binary search algorithm, find $\lfloor \sqrt{n} \rfloor$ for nonnegative integers $n$. The floor function $\lfloor\text{ } \rfloor$ essentially tells you to always round down if $\sqrt{n}$ is a decimal number. You may not use the java.lang.Math.sqrt() function.

Comments: This is a very difficult problem! Try sketching out a rough idea of the algorithm first. Furthermore, do not use recursion for this problem (it becomes impossibly difficult). I would recommend to implement an appropriate while loop for this problem. If you'd like a hint on how to approach this algorithm using binary search, press the "Hint" button below.

Problem 3

Implement a ternary search algorithm, which is a $n$-ary search algorithm with $n=3$. You may write your implementation in the repl.it plugin for Problem 4, in the section with the comment TODO: Problem 3 Implementation. To test your implementation, press the green ![]() button at the top of the plugin.

button at the top of the plugin.

Problem 4

Using your ternary search algorithm implementation from the above problem, compare the time efficiency of binary search versus ternary search in the slowest possible case (which is where the element we’re looking for is at the very end or very beginning of the list) using the code below. Make this comparison through uncommenting the appropriate code in the main() function below, and then running your program.

From above, we asserted that binary search should be faster than ternary search. Is this the case?