Conservation of Angular Momentum (Solutions)

The following solutions are for the problems on angular momentum and conservation of angular momentum here. I encourage you to attempt them by yourself first before looking through the solutions.

Problem 1

This problem is adapted from Serway Physics, 9ed.

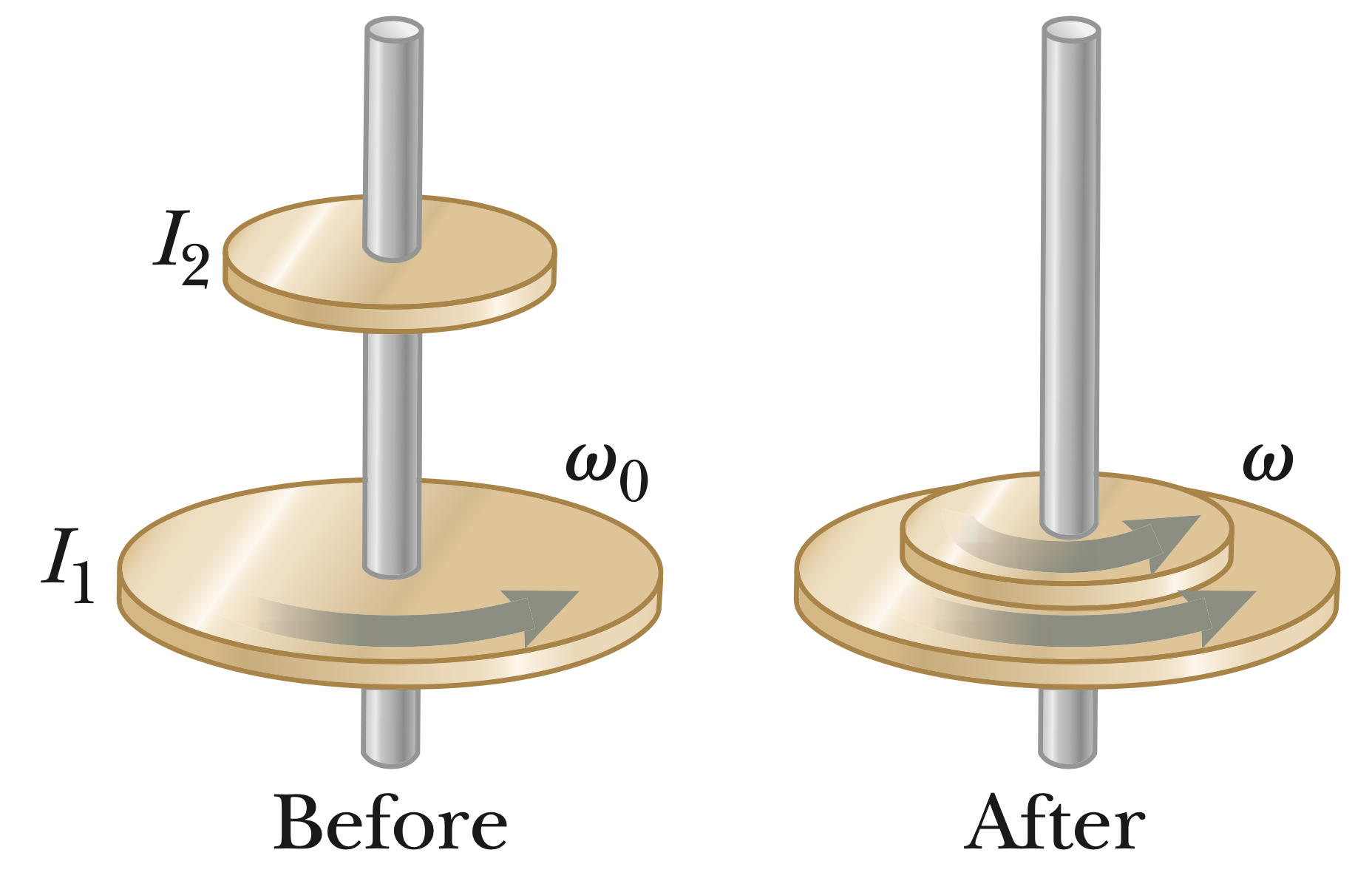

A cylinder with moment of inertia $I_1$ rotates with angular velocity $\omega_0$ about a frictionless vertical axle shown below. A second cylinder, with moment of inertia $I_2$, initially not rotating, drops onto the first cylinder. Because the surfaces are rough, the two cylinders eventually reach the same angular speed $\omega$.

- What is the value of $\omega$ in terms of $\omega_0$, $I_1$, and $I_2$?

- Show that kinetic energy is lost in this situation, and calculate the ratio of the final to the initial kinetic energy.

Because there is no external source of applied torque for this problem, we know that angular momentum is conserved. We know that angular momentum in both the “before” and “after” cases are solely in the $+\hat{z}$ direction since the plates are rotating counterclockwise, and so focusing on the $\hat{z}$ component of the angular momentum $\vec{L}=I\vec{\omega}$, we have

$$I_1\omega_0+I_2(0)=(I_1+I_2)\omega\longrightarrow \omega=\frac{I_1}{I_1+I_2}\omega_0$$

From our discussion on rotational energy, we know that the rotational energy of a rotating object is $U=\frac{1}{I\omega^2}$. Denoting the total energy before as $U_i$ and the total energy after as $U_f$, the change in rotational energy $\Delta U$ can be calculated as

\[\Delta U=U_f-U_i=\frac{1}{2}(I_1+I_2)\omega^2-\left(\frac{1}{2}I_1\omega_0^2+\frac{1}{2}I_2(0)^2\right)=\frac{1}{2}(I_1+I_2)\omega^2-\frac{1}{2}I_1\omega_0^2\]We know that $\omega=\frac{I_1}{I_1+I_2}\omega_0$ from above, and so plugging this into the equation for $\Delta U$ gives

\[\Delta U=\frac{1}{2}(I_1+I_2)\frac{I_1^2}{(I_1+I_2)^2}\omega_0^2-\frac{1}{2}I_1\omega_0^2\]Simplifying this expression algebraically gives

$$\Delta U=-\frac{1}{2}\frac{I_1I_2}{I_1+I_2}\omega_0^2\neq 0\longrightarrow\boxed{\text{Energy is Lost}}$$

Because $\Delta U\neq 0$, we can conclude that energy is lost in this situation. Backtracking our work from above, the ratio $U_f/U_i$ between the final and initial rotational kinetic energy can be calculated as

$$\frac{U_f}{U_i}=\frac{\frac{1}{2}\frac{I_1^2}{I_1+I_2}\omega_0^2}{\frac{1}{2}I_1\omega_0^2}=\frac{I_1}{I_1+I_2}$$

Problem 2

This problem is adapted from Caltech's Ph1a course.

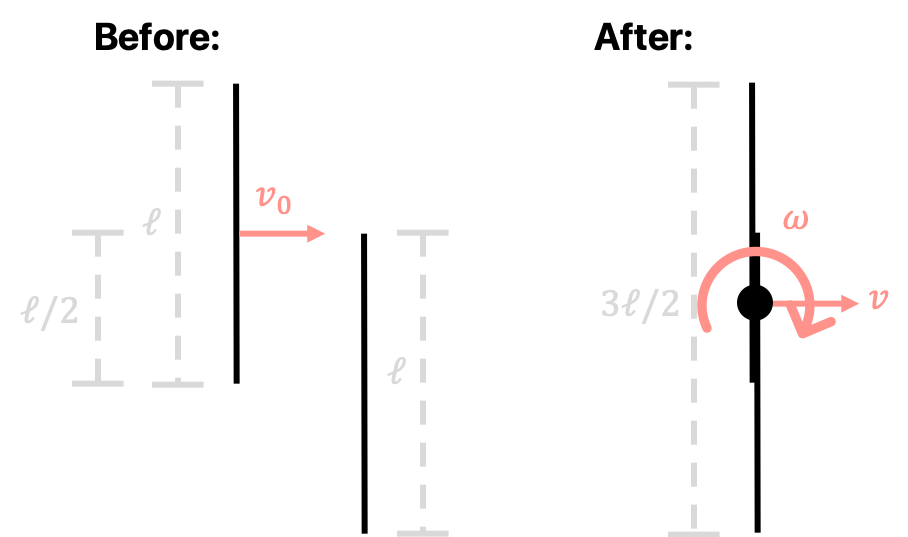

Two equal, uniform, thin rigid rods of each of length $\ell$ and mass $m$ collide and stick together, making a composite rod of length $3\ell/2$. Initially, one rod is at rest while the other approaches with speed $v_0$ perpendicular to both rods.

- What is the velocity $v$ of the center of mass after the collision?

- Find the moment of inertia $I$ for the composite rod about its center of mass. You may assume that the width of the rods, including the composite rod, is negligible, such that the rods are only one-dimensional.

- After the collision, what is the angular velocity $\omega$ of the composite rod about its center of mass?

There are no externally applied forces on this system containing the two rods, and so we can conclude that linear momentum is conserved in this setup. Therefore, using conservation of momentum and equating the total linear momentum from both before and after the collision, we find that

$$mv_0+m(0)=2mv\longrightarrow v=\frac{1}{2}v_0\longrightarrow \vec{v}=\frac{1}{2}v_0\hat{x}$$

Next, to find the moment of inertia $I$ for the composite rod, all we have to do is integrate the contributions from either rod with respect to the center of mass, which, by symmetry, is highlighted with the black circle in the “after” diagram above. Because the rods are given to be uniform, we know that both of their mass densities $\rho$ are given by

\[\rho=\frac{\text{total mass}}{\text{total length}}=\frac{m}{\ell}\]Therefore, we can conclude that $dm=\rho dy=\frac{m}{\ell}dy$, where the $y$ coordinate is along the length of each of the individual rods. Summing the contributions from both of the rods and using the integral definition $I=\int dm\text{ }r^2$ for the moment of inertia, we have

\[I=\frac{m}{\ell}\int_{-\ell/4}^{3\ell/4}dy\text{ }y^2+\frac{m}{\ell}\int_{-3\ell/4}^{\ell/4}dy\text{ }y^2=\frac{m}{3\ell}\left.y^3\right\vert_{-\ell/4}^{3\ell/4}+\frac{m}{3\ell}\left.y^3\right\vert_{-3\ell/4}^{\ell/4}\]Simplifying this expression gives us

$$I=\frac{m}{3\ell}\left(\frac{27\ell^3}{64}+\frac{\ell^3}{64}+\frac{\ell^3}{64}+\frac{27\ell^3}{64}\right)=\frac{7}{24}m\ell^2$$

There are no externally applied torques on this system containing the two rods, and so we can conclude that angular momentum is conserved in this setup. The right rod before the collision was not moving, and so it did not have any angular momentum. However, the left rod had angular momentum, which can be calculated by summing up all of the infinitesimal angular momentum contributions along the rod immediately before colliding with the stationary rod. The momentum vector is perpendicular to the position vector from the center of mass immediately before the collision, and so calculating the cross product $d\vec{r}\times\vec{p}$ is fairly straightforward. Denoting the magnitude of the initial angular momentum as $L_i$,

\[L_i=\int_{-\ell/4}^{3\ell/4} r\text{ }dp=\int_{-\ell/4}^{3\ell/4} rv_0dm=\frac{mv_0}{\ell}\int_{-\ell/4}^{3\ell/4}rdr=\left.\frac{mv_0}{2\ell}r^2\right\vert_{-\ell/4}^{3\ell/4}=\frac{mv_0\ell}{4}\]The final angular momentum of the system $L_f=I\omega$ can be solved using the result for the expression for the moment of inertia that we calculated above.

\[L_f=I\omega=\frac{7}{24}m\ell^2\omega\]Because angular momentum is conserved, $L_i=L_f$, and so

$$\frac{mv_0\ell}{4}=\frac{7}{24}m\ell^2\omega\longrightarrow \omega=\frac{6v_0}{7\ell}$$

Problem 3

This problem is adapted from Caltech's Ph1a course.

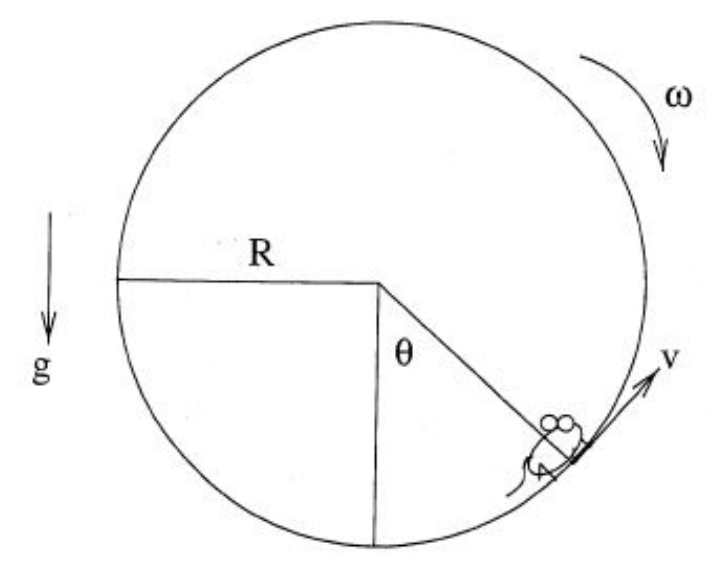

A mouse of mass $m$ runs in an exercise wheel of mass $M$ and radius $R$. The mouse runs at constant speed $v$ relative to the wheel. The wheel has a damping torque proportional to its angular velocity given by $\vert \tau_{\text{damp}}\vert=k\vert \omega\vert$, where $k$ is some positive constant and $\omega$ is the angular velocity. The damping torque can be thought of as a "friction torque" that opposes the direction of angular motion.

- If the mouse is not moving relative to the lab, what is the angular velocity $\omega$ of the wheel in terms of $m, M, R, v, k$?

- What is the angle $\theta$ of the mouse?

- How much power is the mouse delivering? Power is defined to be the time derivative of work, and recall that we showed that the work delivered by the mouse (or any rotating object) is $\int d\theta\text{ }\tau(\theta)$. (Hint: Do not actually evaluate any integral expressions for this problem. Use the definition of power to rewrite power in terms of torque applied by the mouse.

The first part of this problem is fairly simply. In order for the mouse to be stationary relative to the lab, it must be moving at a speed equal to the tangential speed $\omega R$ of the wheel. Therefore,

$$v=\omega R\rightarrow \omega=\frac{v}{R}$$

The angle $\theta$ of the mouse is a bit more difficult to determine. Because the angular speed $\omega$ of the wheel is not changing, we can conclude that the net torque on the wheel must be zero. There are two sources of torque in this problem: the torque due to the weight of the mouse \(\vec{\tau}_g=mgR\sin\theta\hat{z}\), and the damping torque, \(\vec{\tau}_{\text{damp}}=-k\omega\hat{z}\). Taking the sum of these two torque contributions and setting it equal to zero, we have

\[mgR\sin\theta-k\omega=0 \longrightarrow \sin\theta=\frac{k\omega}{mgR}\]From above, we asserted that $\omega=\frac{v}{R}$, and so

$$\sin\theta=\frac{kv}{mgR^2}\longrightarrow \theta=\sin^{-1}\left(\frac{kv}{mgR^2}\right)$$

The mouse is applying a constant force $\vec{F}=-mg\hat{y}$ on the wheel, and so the magnitude of the torque applied by the mouse is $\tau=Rmg\sin\theta_0$. Where \(\theta_0=\sin^{-1}\left(\frac{kv}{mgR^2}\right)\) is the constant angle of the mouse we found above, and not the variable $\theta$. Using the definition of power $P$ given in the problem, we know that

\[P=\frac{d}{dt}\int d\theta\text{ }\tau=Rmg\sin\theta_0\frac{d}{dt}\int d\theta\]We have taken the expression for the torque $\tau$ out of the integral because it is independent of $\theta$. $\int d\theta$ is simply $\theta$, and $\frac{d}{dt}[\theta]=\omega$. Therefore, the expression for the power delivered by the mouse is simply

$$P=R\omega mg\sin\theta_0=mgv\left(\frac{kv}{mgR^2}\right)=\frac{kv^2}{R^2}$$

Problem 4

This is a challenge problem and adapted from MIT Physics.

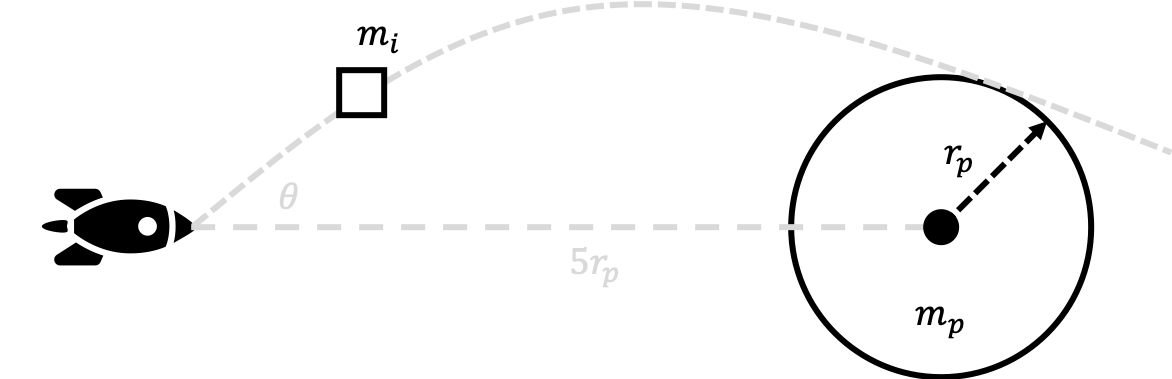

A spaceship is sent to investigate a planet of mass $m_p$ and radius $r_p$. While hanging motionless in space at a distance $5r_p$ from the center of the planet, the ship fires an instrument package with speed $v_0$. The package has mass $m_i$ which is much smaller than the mass of the spacecraft. The package is launched at an angle $\theta$ with respect to a radial line between the center of the planet and the spacecraft. For what angle $\theta$ will the package just graze the surface of the planet?

The solution to this question can be found here on pages 1 through 3 of the linked document.