Conservation of Angular Momentum

Over the three teaching modules, we have focused on how to adapt our mathematical formalism for translational, linear motion to rotational motion. We introduced the following rotational analogs for common translational physical quantities:

| Translational Motion | Rotational Motion |

|---|---|

| Displacement $\Delta \vec{x}$ | Angular Displacement $\Delta \vec{\theta}$ |

| Velocity $\vec{v}$ | Angular Velocity $\vec{\omega}$ |

| Acceleration $\vec{a}$ | Angular Acceleration $\vec{\alpha}$ |

| Mass $m$ | Moment of Inertia $I=mr^2$ |

| Force $\vec{F}_{\text{net}}=m\vec{a}$ | Torque $\vec{\tau}_{\text{net}}=I\vec{\alpha}$ |

| Kinetic Energy $KE=\frac{1}{2}mv^2$ | Rotational Energy $RE=\frac{1}{2}I\omega^2$ |

| Momentum $\vec{p}=m\vec{v}$ | Angular Momentum ? |

As suggested by the table, there is one more quantity that we need to discuss: angular momentum, which we will see is the rotational analog of linear momentum $\vec{p}=m\vec{v}$.

Angular Momentum

Definition of Angular Momentum

Recall the central definition of linear momentum that we introduced previously:

\[\sum\vec{F}=\frac{d\vec{p}}{dt}\]In other words, we managed to show that the net force acting on a particular object is equal to the time derivative of the momentum of the object. To continue our analogy between translational and rotational motion, we shall define the angular momentum of an object $\vec{L}$ in a following manner. Since the net torque is the rotational analog of the net force, we hypothesize that

$$\sum\vec{\tau}=\frac{d\vec{L}}{dt}$$

where $\vec{L}$ is our vector quantity referred to as angular momentum. It turns out that this simple definition is sufficient for us to derive a number of useful expressions and properties about this physical quantity.

Magnitude of Angular Momentum

The magnitude of the angular momentum vector of a particular object can be calculated two different ways. The first method is to use Newton’s second law with regards to rotational motion, which is that the net torque acting on the object is equal to the object’s moment of inertia $I$ multiplied by its angular acceleration $\vec{\alpha}$. Therefore, we can conclude that

\[\sum\vec{\tau}=I\vec{\alpha}=\frac{d\vec{L}}{dt}\]Integrating both sides of this equation gives

\[\vec{L}=\int dt\text{ }I\vec{\alpha}=I\int dt\vec{\alpha}\]where we have made the assumption that the moment of inertia is not changing with respect to time, and so it can be pulled out as a constant factor out of the integral. By definition, the integral of angular acceleration is angular velocity, and so

$$\vec{L}=I\vec{\omega}$$

Note that from this definition of angular momentum and the definitions of the moment of inertia $I=mr^2$ and $\omega=v/r$, where $v$ is the tangential velocity, we can also rewrite the right hand side as

\[\vec{L}=mr^2\frac{v}{r}\hat{\omega}=r(mv)\hat{\omega}\]What is $\hat{\omega}$? Recall from our rotational motion conventions that $\hat{\omega}=\hat{z}$. From our knowledge of cross-products, we know that $\hat{r}\times\hat{\theta}=\hat{z}$. $\hat{r}$ is the direction of the position vector $\vec{r}$, and $\hat{\theta}$ is the direction of the tangential velocity vector $\vec{v}$ (since the object is presumably undergoing circular, rotational motion). Therefore, we can conclude that

\[\vec{L}=r(mv)\hat{z}=(r\hat{r})\times(mv\hat{\theta})=\vec{r}\times(m\vec{v})=\vec{r}\times\vec{p}\]In other words, the angular momentum of a rotating object is equal to the cross product of its position vector $\vec{r}$ and its linear momentum vector $\vec{p}$. Based on the definition of the cross product, the magnitude of $\vec{L}$ can be calculated as

\[L=rp\sin\theta\]where $r$ is the magnitude of $\vec{r}$, $p$ is the magnitude of $\vec{p}$, and $\theta$ is the angle between $\vec{r}$ and $\vec{p}$. We now have two equally valid definitions of the angular momentum vector, both of which can be used to calculate the angular momentum:

$$\vec{L}=I\vec{\omega}=\vec{r}\times\vec{p}$$

Although we can use either one of these formulas to calculate $\vec{L}$, typically one will be more convenience to use than the other. The choice of which formula to use typically boils down to what information is given in the problem or most easy to calculate. If the moment of inertia is given, often times the $I\vec{\omega}$ formula will be easiest. Otherwise, $\vec{r}\times\vec{p}$ is a good choice.

Direction of Angular Momentum

Based on the hypothesized relation between angular momentum and torque from above, we can conclude that

The angular momentum $\vec{L}$ of an object acts in the same direction as the net torque $\sum\vec{\tau}$ acting on the object.

Units of Angular Momentum

The units of angular momentum can be easily figured out using the definition of this quantity from above. We will denote the units of quantity $x$ as $[x]$.

$$[\vec{L}]=[\vec{r}]\cdot[\vec{p}]=(\text{meters})\times\frac{\text{kg}\cdot\text{meters}}{\text{sec}}=\frac{\text{kg}\cdot\text{meters}^2}{\text{sec}}$$

Example Calculation of Angular Momentum

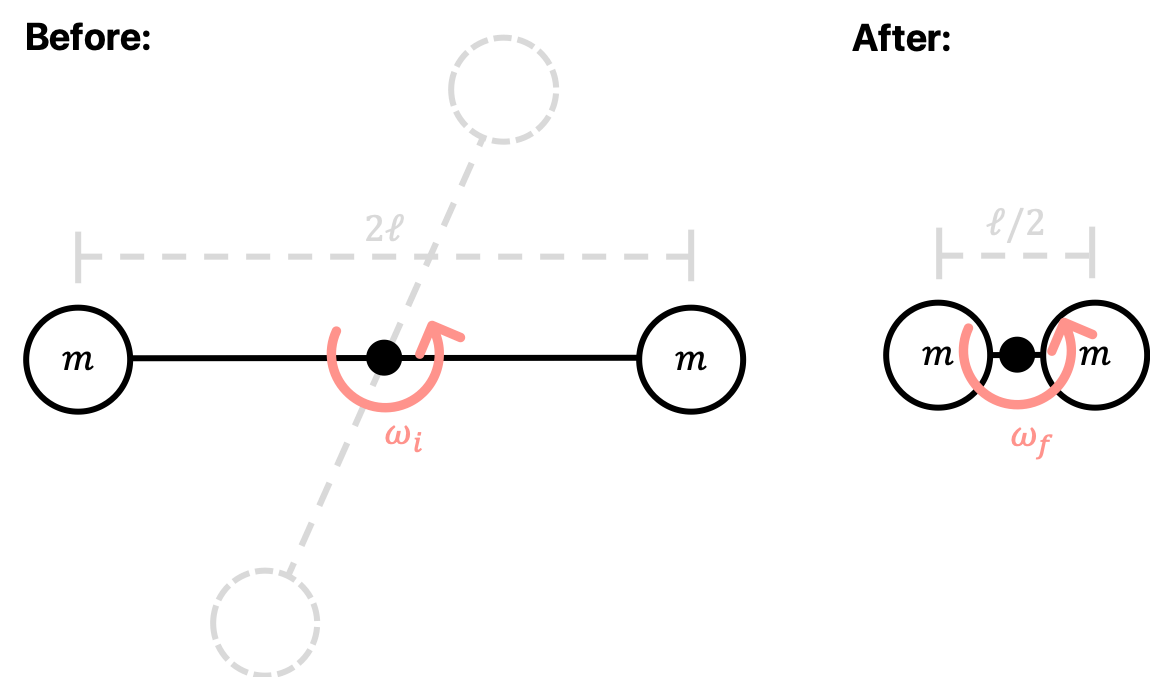

In this section, we’ll briefly walk through an example problem on calculating angular momentum. Consider a system of two masses, each of mass $m$, connected by a massless rigid rod of length $2\ell$. The two masses are rotating around the origin at the center of the rod. After some time, the rod suddenly contracts to length $\ell/2$. Our goal is to calculate the angular momentum of the rod both before and after the contraction.

Before the contraction, the angular momentum is given by

\[\vec{L}_i=I_i\omega_i\hat{\omega}=(m\ell^2+m\ell^2)\omega_i\hat{z}=2m\ell^2\omega_i\hat{z}\]After the rod length contraction, the angular momentum is given by

\[\vec{L}_f=I_f\omega_f\hat{\omega}=\left[m\left(\frac{\ell}{4}\right)^2+m\left(\frac{\ell}{4}\right)^2\right]\omega_f\hat{z}=\frac{1}{8}m\ell^2\omega_f\hat{z}\]Notice that we used the fact that angular momentum is additive. This means that the total angular momentum of two separate objects is equal to the sum of the individual angular momenta of the two individual objects.

Conservation of Angular Momentum

Suppose that the net torque on an object is zero, such that $\sum\vec{\tau}=0$. Based on the definition of angular momentum from above, we can conclude that in this special case,

\[\sum\vec{\tau}=0=\frac{d\vec{L}}{dt}\]This tells us that in the absence of any external applied torque, the angular momentum of a system is conserved and a constant with respect to time!

Notice that this is very similar to when we discussed conservation of linear momentum in collision problems that we discussed previously: in the absence of any external applied force, the linear momentum of a system is conserved. In the case of rotational motion, in the absence of any external applied torque, the angular momentum of a system is conserved.

For example, let’s go back to the example from above. There is no externally applied torque acting on the system: all that is happening between the “before” and “after” is that the length of the rod magically contracts. Therefore, we can conclude that angular momentum is conserved in this system. Equating the angular momentum before and after that we calculated from above, we have

\[2m\ell^2\omega_i=\frac{1}{8}m\ell^2\omega_f \longrightarrow \omega_f=16\omega_i\]From the conservation of the angular momentum, we can conclude that the angular speed of rotation of the object increases by 16 times compared to the initial angular speed! On a tangentially related note, this phenomenon of angular momentum conservation is commonly exploited by dancers and figure skaters: by centering the mass closer to the center of gravity, the moment of inertia of the object decreases, and because angular momentum is conserved, their angular speed of rotation will increase drastically. A good example of this can be found on Youtube:

Recap

This is our last discussion of rotational motion (for a while), so let’s quickly review all of the different aspects of rotational motion and how they are similar to linear motion:

| Translational Motion | Rotational Motion |

|---|---|

| Displacement $\Delta \vec{x}$ | Angular Displacement $\Delta \vec{\theta}$ |

| Velocity $\vec{v}$ | Angular Velocity $\vec{\omega}$ |

| Acceleration $\vec{a}$ | Angular Acceleration $\vec{\alpha}$ |

| Mass $m$ | Moment of Inertia $I=mr^2$ |

| Force $\vec{F}_{\text{net}}=m\vec{a}$ | Torque $\vec{\tau}_{\text{net}}=I\vec{\alpha}$ |

| Kinetic Energy $KE=\frac{1}{2}mv^2$ | Rotational Energy $RE=\frac{1}{2}I\omega^2$ |

| Momentum $\vec{p}=m\vec{v}$ | Angular Momentum $\vec{L}=I\vec{\omega}=\vec{r}\times\vec{p}$ |

Exercises

Problem 1

This problem is adapted from Serway Physics, 9ed.

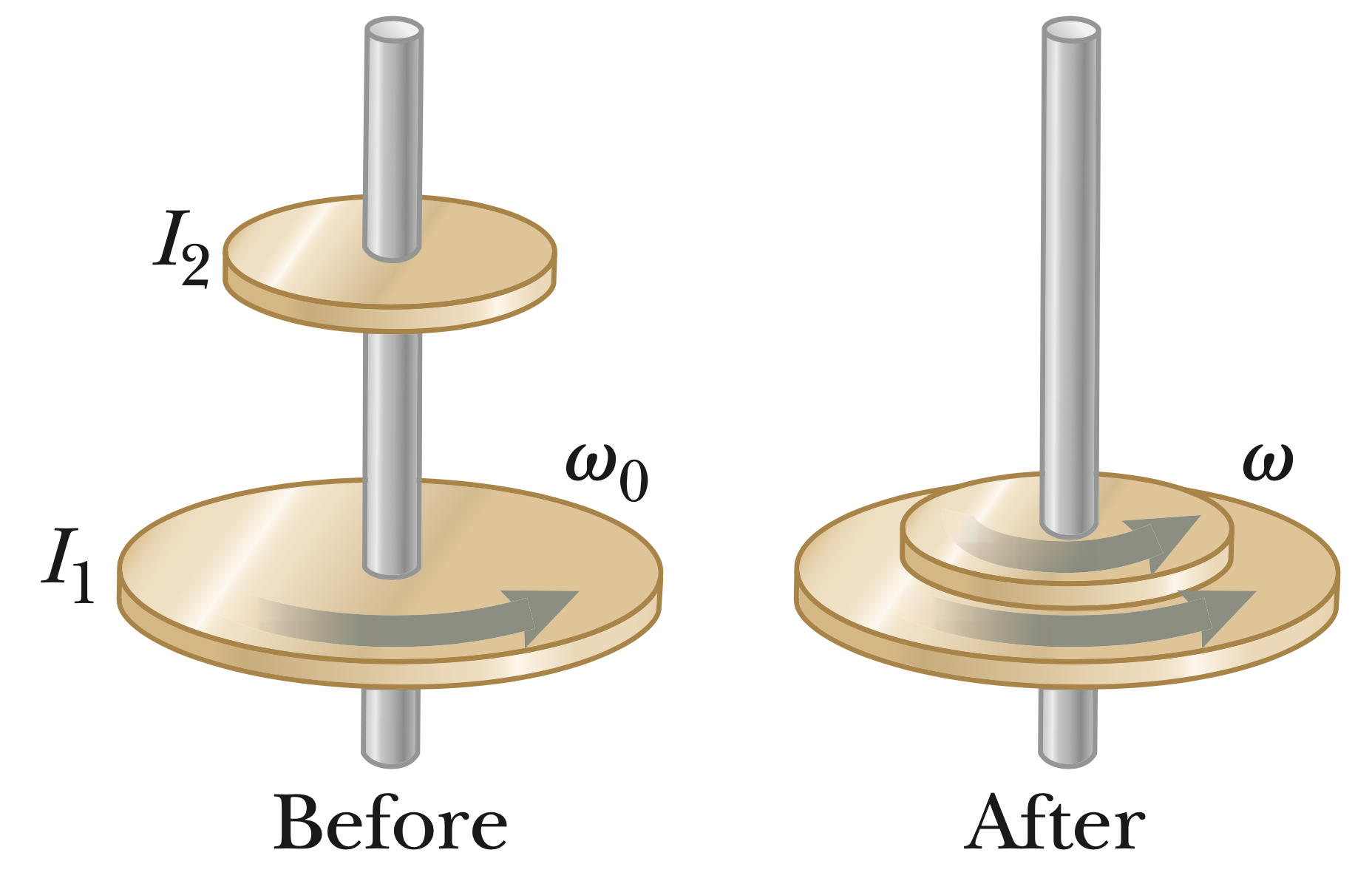

A cylinder with moment of inertia $I_1$ rotates with angular velocity $\omega_0$ about a frictionless vertical axle shown below. A second cylinder, with moment of inertia $I_2$, initially not rotating, drops onto the first cylinder. Because the surfaces are rough, the two cylinders eventually reach the same angular speed $\omega$.

- What is the value of $\omega$ in terms of $\omega_0$, $I_1$, and $I_2$?

- Show that kinetic energy is lost in this situation, and calculate the ratio of the final to the initial kinetic energy.

Problem 2

This problem is adapted from Caltech’s Ph1a course.

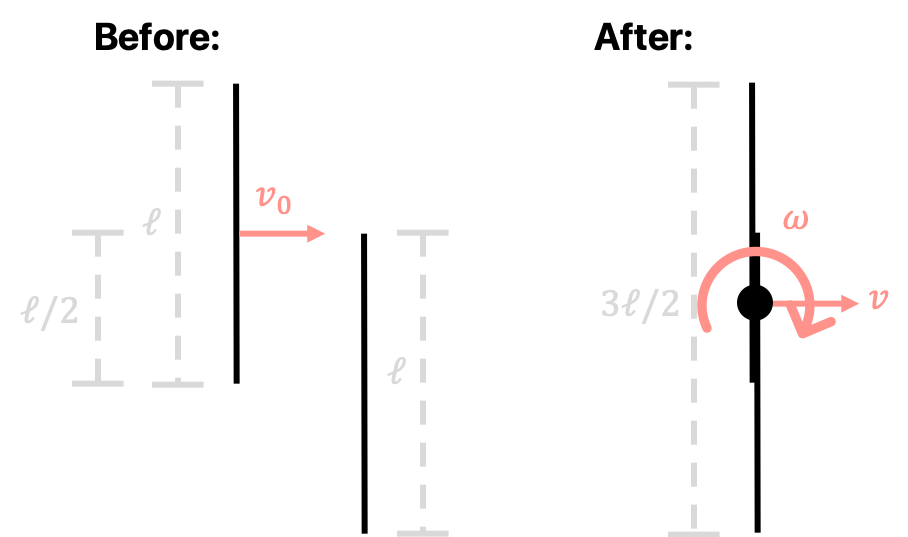

Two equal, uniform, thin rigid rods of each of length $\ell$ and mass $m$ collide and stick together, making a composite rod of length $3\ell/2$. Initially, one rod is at rest while the other approaches with speed $v_0$ perpendicular to both rods.

- What is the velocity $v$ of the center of mass after the collision?

- Find the moment of inertia $I$ for the composite rod about its center of mass. You may assume that the width of the rods, including the composite rod, is negligible, such that the rods are only one-dimensional.

- After the collision, what is the angular velocity $\omega$ of the composite rod about its center of mass?

Problem 3

This problem is adapted from Caltech’s Ph1a course.

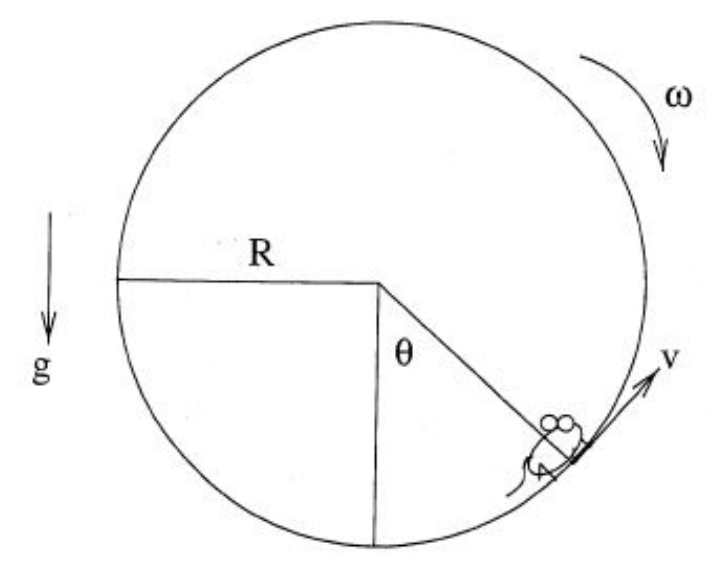

A mouse of mass $m$ runs in an exercise wheel of mass $M$ and radius $R$. The mouse runs at constant speed $v$ relative to the wheel. The wheel has a damping torque proportional to its angular velocity given by $\vert \tau_{\text{damp}}\vert=k\vert \omega\vert$, where $k$ is some positive constant and $\omega$ is the angular velocity. The damping torque can be thought of as a “friction torque” that opposes the direction of angular motion.

- If the mouse is not moving relative to the lab, what is the angular velocity $\omega$ of the wheel in terms of $m, M, R, v, k$?

- What is the angle $\theta$ of the mouse?

- How much power is the mouse delivering? Power is defined to be the time derivative of work, and recall that we showed that the work delivered by the mouse (or any rotating object) is $\int d\theta\text{ }\tau(\theta)$. (Hint: Do not actually evaluate any integral expressions for this problem. Use the definition of power to rewrite power in terms of torque applied by the mouse.)

Problem 4

This is a challenge problem and adapted from MIT Physics.

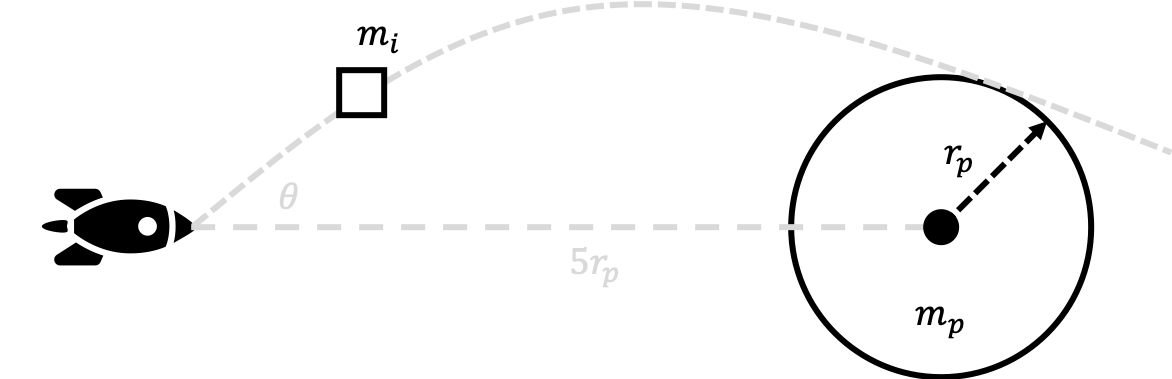

A spaceship is sent to investigate a planet of mass $m_p$ and radius $r_p$. While hanging motionless in space at a distance $5r_p$ from the center of the planet, the ship fires an instrument package with speed $v_0$. The package has mass $m_i$ which is much smaller than the mass of the spacecraft. The package is launched at an angle $\theta$ with respect to a radial line between the center of the planet and the spacecraft. For what angle $\theta$ will the package just graze the surface of the planet?