Practice with Mechanical Equilibrium (Solutions)

The following solutions are for the problems on mechanical equilibrium practice here. I encourage you to attempt them by yourself first before looking through the solutions.

Example 1: Two Masses on an Inclined Plane

This problem is adapted from Caltech's Ph1a course.

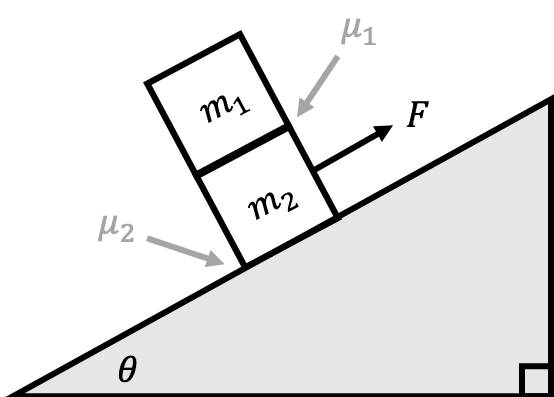

Upon an inclined plane of angle $\theta$ is placed a block of mass $m_2$. Upon $m_2$ is placed another block of mass $m_1$. The coefficient of static friction between $m_2$ and the inclined plane is $\mu_{2s}$ and the coefficient of sliding friction is $\mu_{2k}$. Likewise, the coefficient of static friction between $m_1$ and $m_2$ is $\mu_{1s}$ and the coefficient of sliding friction is $\mu_{1k}$. A force $F$ upward and parallel to the plane is applied to $m_2$.

- What is the acceleration of $m_2$ when $m_1$ just starts to slip on it?

- What is the maximum value of $F$ before this slipping takes place?

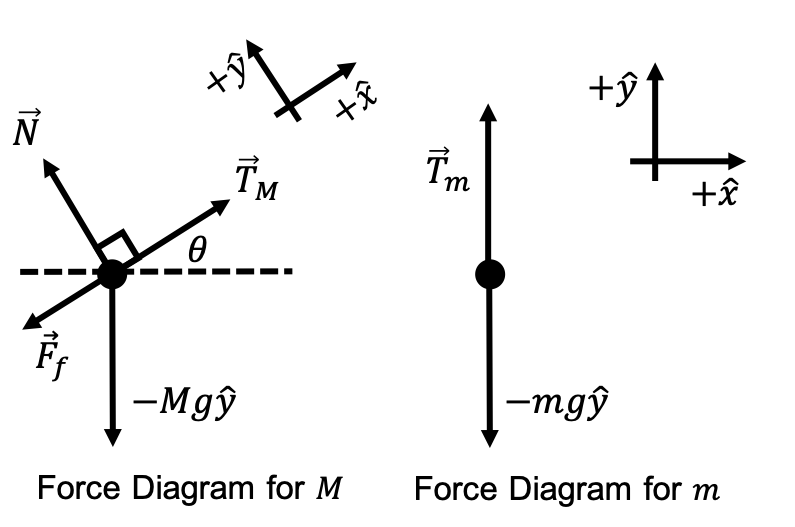

In any of these mechanical equilibrium problems, remember that the initial step is almost always the same: draw force diagrams and set $\sum \vec{F}=0$. Here, we can draw the force diagrams for both masses $m_1$ and $m_2$:

This diagram is complicated, so we’ll explain all of the forces we need to account for:

- Force of gravity. We denote the force of gravity on $m_1$ as \(\vec{F}_{1g}\) and on $m_2$ as \(\vec{F}_{2g}\).

- The applied force on $m_2$, which we denote as $\vec{F}$.

- The normal force on $m_2$ due to the inclined plane, denoted as \(\vec{N}_2\). We also have the normal force on $m_2$ due to the presence of $m_1$, denoted as $\vec{N}_{12}$.

- By Newton’s third law, there is also a normal force on $m_1$ from $m_2$, denoted as \(\vec{N}_{21}=-\vec{N}_{12}\).

- The friction force on $m_2$ due to the inclined plane, denoted as $\vec{F}_{2f}$.

- The friction force on $m_2$ due to $m_1$, denoted as $\vec{F}_{12f}$. By Newton’s third law, there is also a friction force on $m_1$ due to $m_2$, denoted as \(\vec{F}_{21f}=-\vec{F}_{12f}\).

After accounting for all of the forces, we can write the force balance laws for both of the masses in both the $x$ and $y$ directions:

- \(F_{21f}-m_1g\sin\theta=m_1a\) and \(N_{21}-m_1g\cos\theta=0\).

- \(F_{2f}+F-F_{12f}-m_2g\sin\theta=m_2a\) and \(N_2-N_{12}-F_{2g}\cos\theta=0\).

Notice that for two block, we did not set the right hand side of the $\hat{x}$-direction force balance equation equal to zero. This is because as hinted in the problem, we are assuming that both blocks are accelerating up the ramp with magnitude $a$, and we want to find the maximum value of $a$ such that they are both sliding up with this acceleration.

To answer the first question, we’ll consider the first pair of equations. The equilibrium condition in the $\hat{y}$ direction gives us

\[N_{21}=m_1g\cos\theta\]To utilize the second equation, we need to understand what is happening. As the acceleration $a$ increases in magnitude on the right hand side, there must be a corresponding increase in the force of friction $F_{21f}$, since $m_1g\sin\theta$ is a constant and cannot change. However, at a certain point, we reach the maximum force of static friction

\[F_{21f, \text{max}}=\mu_{1s}N_{21}=\mu_{1s}m_1g\cos\theta\]such that if the acceleration increases beyond this point, the block must begin to slip because we can’t provide sufficient static friction to “match” the amount of acceleration. Therefore, the equation that allows us to solve for $a$ is

\[\mu_{1s}m_1g\cos\theta-m_1g\sin\theta=m_1a\]Dividing both sides by $m_1$ gives

$$a=g(\mu_{1s}\cos\theta-\sin\theta)$$

To answer the second part of the question, we can use the equation for the Newton’s second law in the $\hat{x}$-direction for the second block that we found above:

\[F_{2f}+F-F_{12f}-m_2g\sin\theta=m_2a\]Again, thinking about what is happening in this situation, we know from our work in the first part of the problem that there is an upper limit on the value of $a$, and so therefore, there is also an upper limit on the left hand side. Everything on the left hand side is a constant except for $F$. By Newton’s 3rd Law, we know that $F_{12f}=\mu_{1s}m_1g\cos\theta$, and $F_{2f}=\mu_{2k}N_2=\mu_{2k}(m_1+m_2)g\cos\theta$. Therefore, solving for $F$ gives

$$F=m_2g(\mu_{1s}\cos\theta-\sin\theta)-\mu_{2k}(m_1+m_2)g\cos\theta+\mu_{1s}m_1g\cos\theta+m_2g\sin\theta$$

After some (pretty intense) algebraic simplification, we arrive at the result

$$F=(m_1+m_2)g(\mu_{1s}-\mu_{2k})\cos\theta$$

Example 2: A Hanging Rope

This problem is adapted from Caltech's Ph1a course.

A rope of length $2l$ and uniform density (here: mass per unit length) $\rho$ is hanging over a nail in a wall with a piece of length $l$ on both sides. Friction, the thickness of the nail, and the thickness of the rope are negligible. When one creates a slight length difference between the two sides, a net force will start to act on the rope, and it will slide off the nail, faster and faster.

- When the length on one side is $l+x$ (with $0 < x < l$), what is the net force on the rope?

- Find the velocity as a function of $x$. Hint: make use of $\frac{dv}{dt}=\frac{dv}{dx}\frac{dx}{dt}$. What is the velocity when the rope completely comes off the nail?

When both sides of the rope are the same length, then our physical intuition tells us that the rope is in mechanical equilibrium. This is because the gravitational force is equal on both sides of the rope. What happens when the length on one side is $l+x$? The gravitational force on this side is $F_{>}=mg=\rho(l+x)g$. Meanwhile, the gravitational force on the other side is $F_{<}=mg=\rho(l-x)g$. Therefore, the magnitude of the net downwards force on the rope is

$$F_{\text{net}}=F_{>}-F_{<}=\rho(l+x)g-\rho(l-x)g=2\rho xg$$

This answer the first question. The mass of the entire rope is $2\rho l$, meaning that the acceleration of the rope due to this force is $a=\frac{dv}{dt}=\frac{xg}{l}$. At this point, we can make the educated guess that $v=\frac{dx}{dt}=x\sqrt{g/l}$, which that $\frac{dv}{dx}=\sqrt{g/l}$. Plugging this into the hint gives us the expected result, allowing us to conclude that the velocity of the rope as a function of $x$ is given by

$$\vec{v}=-x\sqrt{\frac{g}{l}}\hat{y}$$

and so the velocity \(\vec{v}_{\max}\) when the rope completely comes off at $x=l$ is

$$\vec{v}_{\text{max}}=-\hat{y}\sqrt{gl}\hat{y}$$

Example 3: Pulley on an Inclined Plane

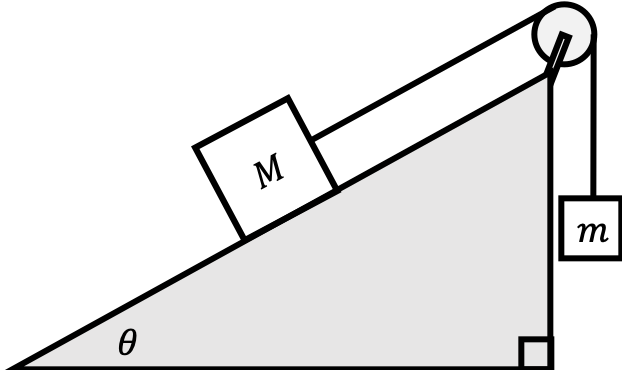

Two blocks of mass $m$ and $M$ are connected via pulley with a configuration shown below:

The coefficient of static friction is $\mu_s$ between the block and surface. What is the minimum and maximum mass $M$ so that no sliding occurs?

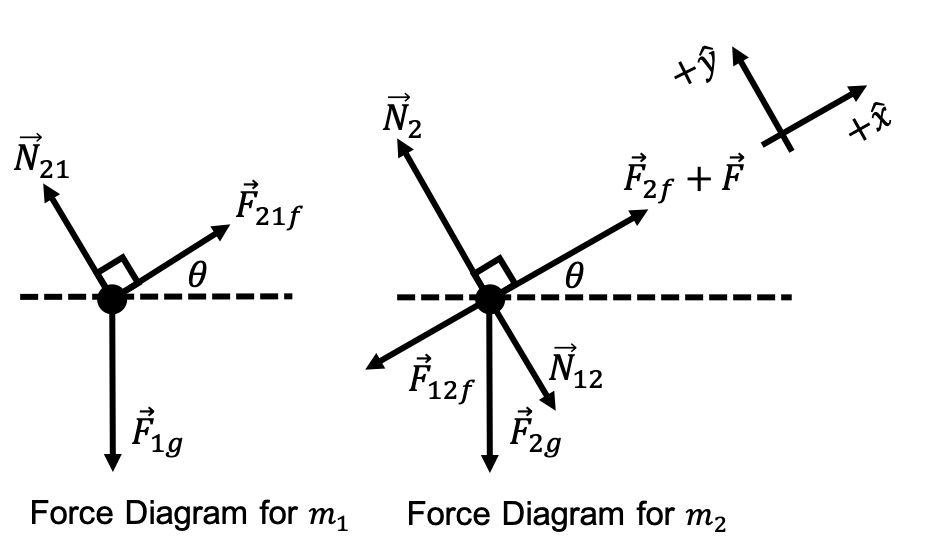

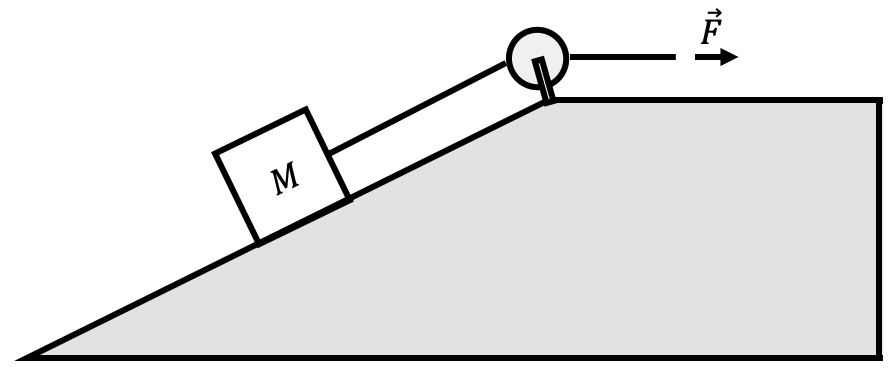

Again, let’s refer back to our problem-solving algorithm from Problem 1. First, let’s draw the force diagrams for both of the masses:

From last time, we know that the pulley gives us that equal magnitude of acceleration and also equal force. This means that $T_M=T_m$ and the acceleration magnitudes are the same. We can then write down the mechanical equilibrium force balance laws for mass $M$, given that we have $mg-T_m=mg-T_M=0$ for mass $m$ (we set the net force equal to zero because we want the mass $m$ to be in mechanical equilibrium):

- $T_M+F_f-Mg\sin\theta=mg+\mu_sN-Mg\sin\theta=0$

- $N-Mg\cos\theta=0$

Again, note that we set the net force in both the $\hat{x}$ and $\hat{y}$ directions equal to zero because mass $M$ should also be in mechanical equilibrium. The second equation tells us that $N=Mg\cos\theta$, and so plugging this into the first equation and using $T_M-mg=0$ gives us

\[mg+\mu_sMg\cos\theta-Mg\sin\theta=0\]Therefore, we can conclude that

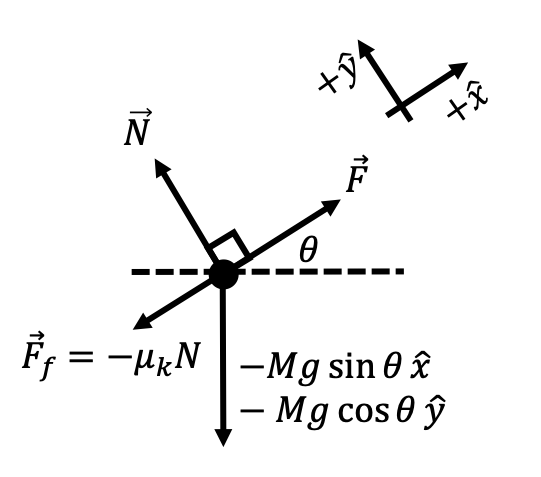

\[M=\frac{m}{\sin\theta-\mu_s\cos\theta}\]This represents our first bound on $M$. Notice that in this diagram, the force of friction is in the $+\hat{x}$ direction. Intuitively, this occurs when the mass $M$ is so massive that it has the “desire” to slide down the ramp, even with the extra force of being tethered to mass $m$. $M$ could be very light and therefore be pulled upwards by the mass $m$ as well. In this case, the force of friction would run in the opposite direction, giving us the following force diagrams:

This changes our $\hat{x}$ equilibrium equation to $T_m-\mu_sN-Mg\sin\theta=0$, and after plugging in $N=Mg\cos\theta$ once more, $M=\frac{m}{\sin\theta+\mu_s\cos\theta}$. Therefore, our range of possible $M$ values before the block begins to slip is

$$\frac{m}{\sin\theta+\mu_s\cos\theta}< M <\frac{m}{\sin\theta-\mu_s\cos\theta}$$

Example 4: Pulley on an Inclined Plane (Again)

This problem is adapted from this link.

A block of mass $M$ is pulled using a pulley at constant velocity along a surface inclined at angle $\theta$. The coefficient of kinetic friction is $\mu_k$, between block and surface. Determine the pulling force $F$.

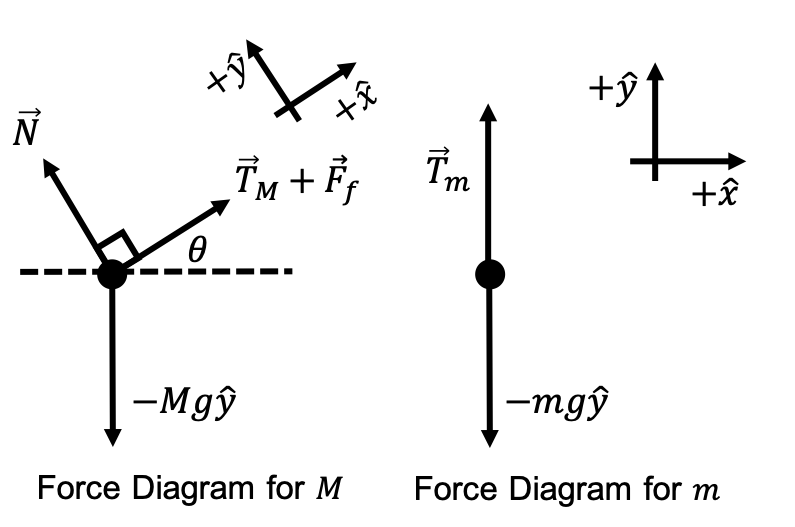

Because we know that forces are distributed uniformly along a single rope in a pulley setup, the tension in the rope that is holding the mass $M$ up from falling down the inclined plane is equal to the applied force in terms of magnitude. Therefore, we can draw the following force diagram for the mass $M$ moving at constant velocity:

This is assuming that the mass is moving up the inclined plane and not down the incline plane. Because the mass is moving at constant velocity, the net force on the mass must be zero. Therefore, the force balance equation in the $\hat{y}$ direction gives us

\[N-Mg\cos\theta=0\longrightarrow N=Mg\cos\theta\]The force balance equation in the $\hat{x}$ direction gives us

\[F-\mu_kN-Mg\sin\theta=0\]Plugging in our expression for $N$ from above gives

\[F-\mu_kMg\cos\theta-Mg\sin\theta=0\]Solving for the magnitude of the pulling force gives

$$F=Mg(\mu_k\cos\theta+\sin\theta)$$

Example 5: Two Pulleys

This problem is adapted from this link.

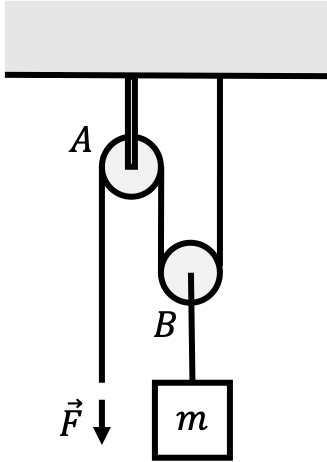

A block of mass $m$ is lifted at constant velocity using the two pulleys shown.

Determine the magnitude of the pulling force $F$. Ignore the mass of the pulleys.

Constant velocity means that the mass $m$ is not accelerating, which also means that the net force acting on the block is zero. Because there is only a single rope in this pulley system, this means that the pulling force $F$ is constant throughout the length of the pulley. If we consider the force balance equation for Pulley $B$,

\[T+T-mg=0\longrightarrow 2T=mg\]Simplifying this equation gives us that magnitude of the tension in the rope $T=\frac{1}{2}mg$. Since the pulling force must have the same magnitude as the tension in the rope, we have

$$F=\frac{mg}{2}$$