Momentum and Collisions

Imagine that we have two cars that are traveling head on and collide with one another. Hopefully you don’t have personal experience with this, but the result of such a collision is often catastrophic if not deadly. Compare this with, say two ants that are traveling head on and accidentally bump into each other. I can hardly make the conclusion that the ants will be only slightly inconvenienced at most. Physically, these two collision events are the same, so why are their outcomes so extremely different?

In today’s lesson, we’ll be exploring the answer to this question in our discussion on collision problems, and the related physical quantity of momentum.

Definition of Momentum

Let’s go back to our comparison between the head-on car collision versus the head-on ant collision. Intuitively, we might expect that the outcomes between these two events are drastically different because of how difficult it is to stop each of the moving objects in each of the two cases. In particular, a car traveling at 60 mph is much more difficult to stop than an ant traveling at 0.01 mph. In order to quantify how difficult it is to stop a particular moving object, we can define some physical parameter to represent this “difficulty.” Let’s call this parameter momentum.

The next step is to figure out a mathematical definition for momentum. In terms of the physical quantities, we can also compare what are the differences between the two situations. One difference is that a car is much more massive than an ant, and another difference is that a car is also traveling much faster than an ant. Other than that, these two systems are essentially physically identical. This tells us that the momentum can be accurately defined in terms of both the mass $m$ and velocity $v$ of an object to quantify how difficult it is to stop it.

This motivation gives us the following definition of the momentum $\vec{p}$ of an object:

\[\vec{p}=m\vec{v}\]This equation tells us that since $\vec{v}$ is a vector quantity and $m$ is a scalar quantity, the momentum $\vec{p}$ is also a vector quantity. Using this equation, we can also figure out the units of momentum:

\[[p]=[m][v]=\text{kg}\cdot\frac{\text{meters}}{\text{sec}}=\frac{\text{kg}\cdot\text{meter}}{\text{sec}}\]Defining Momentum in Terms of Force

Note that if we assume that the mass of the object remains constant over time (which is typically a fairly good assumption), then we can write the following by starting off with the definition of the net force from Newton’s second law, and then using the fact that acceleration $\vec{a}$ is the first time derivative of the velocity $\vec{v}$.

\[\sum \vec{F}=m\vec{a}=m\frac{d\vec{v}}{dt}=\frac{d}{dt}\left[m\vec{v}\right]=\frac{d\vec{p}}{dt}\]Therefore, we can conclude that

\[\sum \vec{F}=\frac{d\vec{p}}{dt}\]This gives us an easy way to relate the net force acting on an object and the object’s momentum. The net force is the time derivative of momentum.

Note that previously, we have defined energy $U$ of an object to be $U=-\frac{dF}{dx}$. Both energy and momentum are related to the net force on an object through a first derivative, and so it’s often pretty easy to mix the two up. It’s important to keep straight that force is related to the time derivative of momentum, and the space derivative of energy.

Defining Kinetic Energy in Terms of the Momentum

Recall from last time that we proved the kinetic energy $T$ of an object to be

\[T=\frac{1}{2}mv^2\]Let’s define $p=\vert \vec{p}\vert$ to be the magnitude of the momentum vector of an object. Because $p=mv$ from the definition of momentum, we know that $v=p/m$. Plugging this into the definition of kinetic energy gives

\[T=\frac{1}{2}m\left(\frac{p}{m}\right)^2=\frac{m}{2}\cdot\frac{p^2}{m^2} \longrightarrow T=\frac{p^2}{2m}\]We now have two definitions for the kinetic energy of an object: one that involves the velocity $v$, and one that involves the momentum $p$. Both of these formulas should give us the same result, so you can use either one when approaching a particular problem (although depending on what information is given in the problem, one formula might be easier than the other in some situations).

Impulse

Often times, especially when two objects are colliding, we’re interested in how the momentum changes over a set period of time. We define the impulse $\vec{I}$ delivered to an object over a time interval $\Delta t = t_f-t_i$ by

\[\vec{I}=\int_{t_i}^{t_f}dt\text{ }\vec{F}_{\text{net}}=\vec{p}_f-\vec{p}_i\]Here, the subscript $f$ refers to the quantity in the final state, while the subscript $I$ refers to the quantity in the initial state. Note that if the force $\vec{F}_{\text{net}}$ is constant with respect to time, then the definition for the impulse $\vec{I}$ simplifies to

\[\vec{I}=\vec{F}\Delta t=\vec{F}(t_f-t_i)=\vec{p}_f-\vec{p}_i\]Clearly, from this equation, we can see that the impulse of the force acing on an object equals the change in momentum of that object. This is referred to as the impulse-momentum theorem.

Conservation of Momentum

In any system (meaning any collection of objects), the total momentum is always conserved in the absence of any external forces. The fact that the momentum of a system is conserved is very important for when we talk about collisions below, but it is true for any system.

The reason why total momentum is conserved in the absence of any external forces is simply due to a result that we provide earlier above:

\[\frac{d\vec{p}}{dt}=\sum\vec{F}\]If there is no net external force, then the right hand side of this equation is equal to zero, and so

\[\frac{d\vec{p}}{dt}=0\]This tells us that the total momentum of the system is independent of time, meaning that it is a conserved quantity.

Collisions in One-Dimension

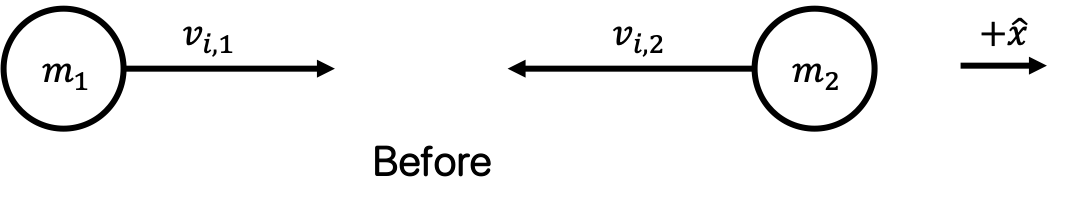

Now that we have the basics of momentum and impulses established, we can talk more quantitatively about collisions. Let’s start with the simplest case of two objects traveling towards each other in one dimension.

The total momentum of this system prior to the collision is

\[m_1v_{i, 1}-m_2v_{i, 2}\]The negative sign for the momentum contribution from $m_2$ is due to the face that $m_2$ is traveling in the $-\hat{x}$ direction. The subscripts $i$ signify that the velocity quantities are the initial quantities prior to the collision.

At this point this is the furthest we can go. This is because there are two separate types of collision problems that we need to consider separately: inelastic and elastic collisions.

Inelastic Collisions

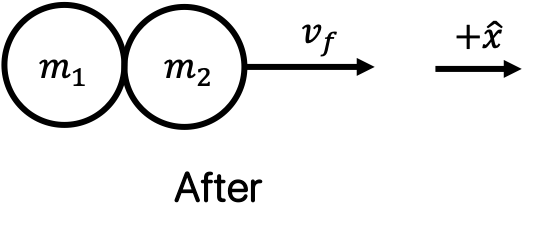

By definition, an inelastic collision is a collision in which momentum is conserved, but kinetic energy is not. The energy can be lost in the form of heat or friction, or it can be absorbed by the molecules within the colliding objects. When two objects collide and stick together to form one single object, the collision is referred to as perfectly inelastic. Let’s sketch what happens after a perfectly inelastic collision:

Here, the two colliding objects have essentially stuck together to form one single, more massive object of mass $m_1+m_2$ with outgoing velocity $v_f$. The final momentum of this system after the collision is $(m_1+m_2)v_f$. Recall that since there are no external forces acting on the objects in this system, we know that momentum is conserved. Therefore, the total momentum of the system before the collision is equal to the total momentum of the system after the collision:

\[m_1v_{i, 1}-m_2v_{i, 2}=(m_1+m_2)v_f\]This equation allows us to solve for \(v_f\) in terms of the masses of the objects and the initial velocities:

\[v_f=\frac{m_1v_{i, 1}-m_2v_{i, 2}}{m_1+m_2}\]Using this result, we can also calculate the total loss in energy $\Delta U=U_f-U_i$ in the system, assuming that the only type of energy that we need to account for is kinetic energy.

\[\Delta U=\frac{1}{2}(m_1+m_2)v_f^2-\left(\frac{1}{2}m_1v_{i, 1}^2+\frac{1}{2}m_1v_{i, 2}^2\right)\]If we plug in the expression for $v_f$ from above and simplify algebraically, we get that the loss in energy is equal to

\[\Delta U=-\frac{m_1m_2(v_{i, 1}+v_{i, 2})^2}{2(m_1+m_2)}\]Elastic Collisions

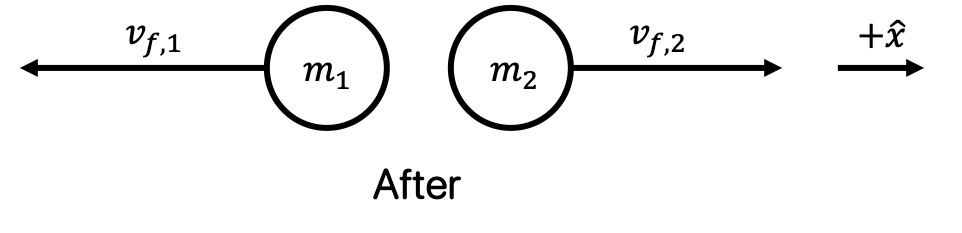

If inelastic collisions are defined in terms of when kinetic energy is not conserved, then we could probably reasonably hypothesize that elastic collisions are defined in terms of when kinetic energy is conserved. In this case, it is not possible for the two colliding objects to both have the same velocity; they will collide and then start moving in the opposite direction, giving the resulting picture after the collision:

Because energy is conserved, we have the following equation relating the kinetic energies of the masses both before and after the collision:

\[\frac{1}{2}m_1v_{i, 1}^2+\frac{1}{2}m_2v_{i, 2}^2=\frac{1}{2}m_1v_{f, 1}^2+\frac{1}{2}m_2v_{f, 2}^2\]We can rewrite this equation in the following way

\[\frac{1}{2}m_1(v_{f, 1}^2-v_{i, 1}^2)=\frac{1}{2}m_2(v_{i, 2}^2-f_{f, 2}^2)\]Factoring both sides and multiplying both sides by $2$ gives us

\[m_1(v_{f, 1}+v_{i, 1})(v_{f, 1}-v_{i, 1})=m_2(v_{f, 2}+v_{i, 2})(v_{i, 2}-v_{f, 2})\]Now, we can also use the fact that the momentum is conserved in this system to equate the total momentum before the collision with the total momentum after the collision:

\[m_1v_{i, 1}-m_2v_{i, 2}=-m_1v_{f, 1}+m_2v_{f, 2} \longrightarrow m_1(v_{f, 1}+v_{i, 1})=m_2(v_{f, 2}+v_{i, 2})\]We can plug in this result due to conservation of momentum into the equation that we derived from the conservation of energy:

\[v_{f, 1}-v_{i, 1}=v_{i, 2}-v_{f, 2}\]Therefore, our system of equations that fully describes the system is

\[m_1(v_{f, 1}+v_{i, 1})=m_2(v_{f, 2}+v_{i, 2}) \text{ and }v_{f, 1}-v_{i, 1}=v_{i, 2}-v_{f, 2}\]Often times, we are trying to solve for two of the variables in terms of all of the other variables in the problem. Perhaps the most common application is solving for the outgoing velocities of the two objects, $v_{f, 1}$ and $v_{f, 2}$.

The Real World

In reality, most collisions are neither perfectly inelastic or perfectly elastic; they are often somewhere in between on a continuum. However, in many practical cases, we can approximate a nearly perfectly inelastic collision as perfectly inelastic for convenience, or a nearly perfectly elastic collision as perfectly elastic for mathematical convenience. In general, things made out of rubber and other elastic, “bouncy” materials will generally have more elastic collisions, while things made out of more absorbent materials will generally have more inelastic collisions.

Collisions in Multiple Dimensions

Recall from our work on analyzing systems in mechanical equilibrium that we were able to tackle an $n$-dimensional problem by splitting it up into $n$ $1$-dimensional force balance problems. Since momentum $\vec{p}$ is also a vector, the same approach can be applied here: simply balance the appropriate vector components of the momentum vectors before and after the collision.

Exercises

Problem 1

This problem is adapted from Caltech’s Physics 1a course.

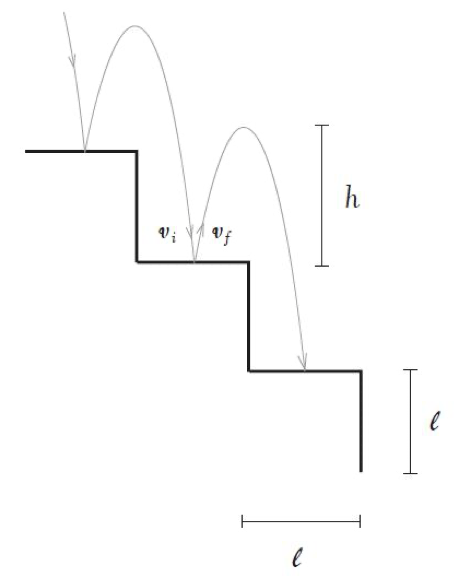

A marble bounces regularly down a long flight of stairs, hitting each step with the same speed and at the same distance from the edge, and then bouncing up to the same height $h$ above the step, as shown in the figure below.

Each stair has the same height and depth $\ell$. The horizontal component of the marble’s velocity is constant throughout, but the stairs have the property that $-v_f/v_i=e$, where $v_i$ and $v_f$ are the vertical velocity components just before and just after the bounce respectively, and $e$ is a constant $0<e<1$.

- Find an expression for $v_i$ in terms of $e, \ell$ and the gravitational acceleration $g$.

- Find an expression for the time $t$ between successive bounces, in terms of $e, \ell, g$.

- Find an expression for the bounce height $h$ in terms of $e$ and $\ell$.

Problem 2

This problem is adapted from Serway Physics, 9ed.

A railroad car of mass $M$ moving at speed $v_1$ collides and couples with two coupled railroad cars, each of the same mass $M$ as the single car and moving in the same direction at speed $v_2$. All of the cars are moving to the right before the collision.

- What is the final speed $v_f$ of the three coupled cars after the collision in terms of the variables given in the problem?

- How much kinetic energy is lost in the collision in terms of the variables given in the problem?

Problem 3

This problem is adapted from Caltech’s Physics 1a course.

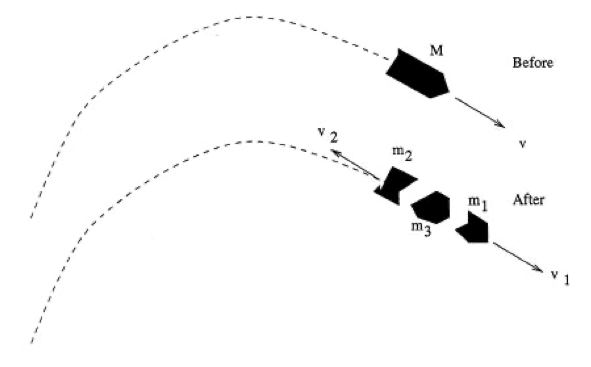

A projectile of mass $M$ initially traveling with speed $v$ explodes in flight into three fragments (see below). An energy $E$ equal to $5$ times the initial kinetic energy of the projectile is released in the explosion, and is transformed into additional kinetic energy of two of the projectiles. One fragment of mass $m_1=M/2$ travels with speed $v_1=k_1v$ in the original direction of the projectile, while the second fragment of mass $m_2=M/6$ travels in the opposite direction with speed $v_2=−k_2v$ and the third fragment of mass $m_3=M/3$ is at rest the instant after the explosion.

Answer the following two questions.

- Write down equations expressing the conservation of momentum and energy in terms of $M$, $k_1$, $k_2$, $v$ and $E$ immediately after the explosion.

- Find the values of $k_1$ and $k_2$.