Springs and Harmonic Oscillation

The Setup: Hook’s Law

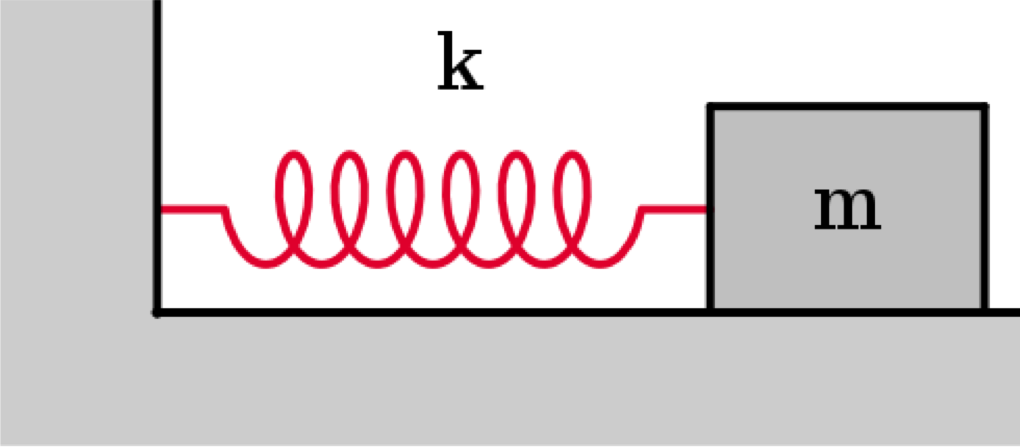

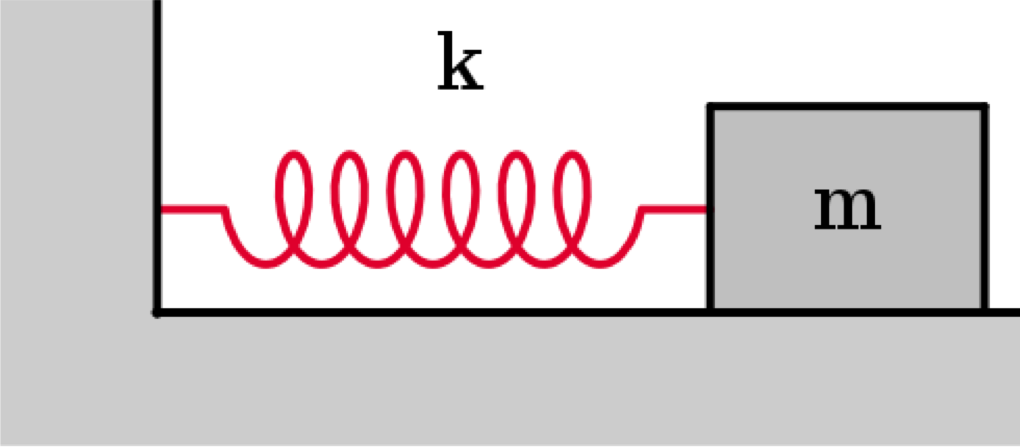

Today, we will be discussing oscillations, which is essentially a fancy name for something that repeats over and over again in a periodic fashion. To motivate this discussion, consider a block of mass $m$ connected to a spring while sitting on a frictionless plane.

Image obtained from Wikimedia Commons.

We will discuss the parameter $k$ later.

Intuitively, we might know a little bit about what springs look like in real life. They are everyone around us, including in pogo sticks, slinky toys, and batteries. In each of these situations, each of the springs has a rest length, which is its typical length is the spring is simply left alone. When we manually try to stretch out the spring, this task becomes more and more difficult the further that we try to stretch it out. Similarly, when we manually try to compress the string, this task becomes increasingly difficult the more we try to compress it. In other words, springs have the ability to change their length, but will resist these changes in the process. There is a force that springs will exert on our hands to prevent us from compressing or stretching it too much. This force is called a restorative force.

Furthermore, because it becomes increasingly difficult to stretch or compress the spring the more it is deviated from its equilibrium length, we would imagine that the restorative force is proportional to this deviation from the equilibrium length. Indeed, if $x=0$ is set to be the equilibrium length of the spring, then the restorative force is given by Hook’s Law:

\[\vec{F}_{\text{spring}}=-kx\hat{x}\]Here, $x$ represents the deviation in length from the equilibrium rest length of the spring. The negative sign represents the fact that the force is a restorative force and tries to counteract changes in its length. $k$ is the proportionality constant between the spring-derived force and the displacement of the spring, and is referred to as Hooke’s constant. In general, a large value of $k$ means that the spring is very stiff and rigid, while a small value of $k$ means that the spring is flexible. The units of $k$ is $[k]=\frac{\text{N}}{\text{m}}=\frac{\text{kg}}{\text{sec}^2}$. The model of Hook’s law assumes that the spring doesn’t permanently deform in shape as a result of being stretched or compressed. If the displacements from equilibrium length are small (which they usually are), and the spring isn’t super poor quality (which they usually aren’t), then this is usually a good assumption to make.

To recap, if some object is connected to a spring, the spring can exert a restorative force on the object with magnitude proportional to the displacement of the object from the rest length of the spring.

Force Diagram

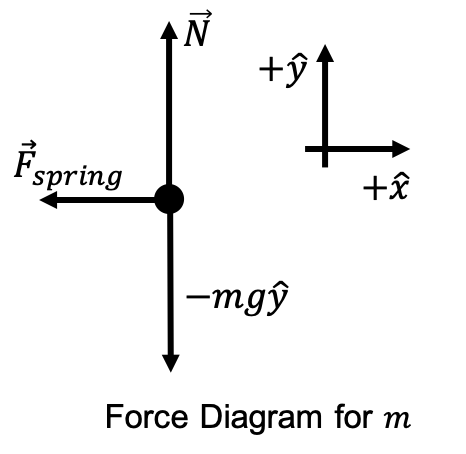

Let’s go back to the original problem above we were considering of a block of mass $m$ connected to a spring on a frictionless plane.

In order to describe the motion of the mass, we need to draw a force diagram (as always). Many of the forces acting on the mass have already been seen before: gravity and normal force, for example. However, we now have a new contribution from the restorative spring force. Together, the force diagram will look something like

Intuitively, we don’t expect the mass to suddenly start “jumping around” or have any motion in the $+\hat{y}$ direction, so we don’t consider that uninteresting force balance equation. However, in the $\hat{x}$ direction, based on Newton’s second law, we know that

\[ma_x=F_{\text{spring}}\longrightarrow m\frac{d^2x}{dt^2}=-kx \longrightarrow \frac{d^2x}{dt^2}=-\frac{k}{m}x\]Here, we used the definition of acceleration and the spring force based on Hook’s Law from above, and then simplified the equation. You will see this equation come up all the time. This is the simple harmonic oscillator (SHO) differential equation, also abbreviated as the SHODE. We will see later why this is called simple harmonic oscillation, or also simple harmonic motion.

Solving the SHODE

To reiterate, in order to fully describe the time evolution of the mass $m$ in the $\hat{x}$ direction, we are interested in solving the equation

\[\frac{d^2x}{dt^2}=-\frac{k}{m}x\]You might be familiar already with how to solve this equation using methods from Calculus AB or BC, but in physics, we’re often not super interested in proving that a particular solution is correct. Rather, using physical intuition and our past experience in solving differential equations, we are more interested in making an Ansatz for the solution to this equation. This is a fancy way of saying that we’re going to make a guess for the form of $x(t)$ and just check if its correct. In this case, we can see that the second derivative must be proportional to the function. There are only two families elementary functions that satisfy this property: the exponential function $e^x$, and the trigonometric functions $\sin x$ and $\cos x$. Intuitively, we don’t expect the displacement of the mass to blow up to $\infty$ over time, so this tells us that perhaps the sine and cosine solutions might best describe our solution. Now, we can make the Ansatz that $x(t)$ has the functional form

\[x(t)=A\sin\left(\omega t\right)+B\cos\left(\omega t\right)\]Here, $A$ and $B$ represent some constants that we have yet to determine, and $\omega$ represents another parameter that we need to solve for. If we take the first derivative of this function with respect to $t$, we have

\[\frac{dx}{dt}=A\omega\cos(\omega t)-B\omega\sin(\omega t)\]Differentiating once more gives

\[\frac{d^2x}{dt^2}=-A\omega^2\sin(\omega t)-B\omega^2\cos(\omega t)=-\omega^2(A\sin(\omega t)+B\cos(\omega t))\]However, since, \(x(t)=A\sin\left(\omega t\right)+B\cos\left(\omega t\right)\) from above, we have

\[\frac{d^2x}{dt^2}=-\omega^2 x(t)\]This exactly matches the original differential equation, so long as $\omega^2=k/m$. This confirms that as long as $\omega=\sqrt{k/m}$, our Ansatz is the correct solution to the differential equation:

\[x(t)=A\sin\left(t\sqrt{\frac{k}{m}}\right)+B\cos\left(t\sqrt{\frac{k}{m}}\right)\]What does this function look like physically? Check out this computational model in Mathematica to see visually what this system looks like. As we can see, the mass on a spring will oscillate in a sinusoidal manner due to the spring in the absence of friction. As we have shown, the frequency of this oscillation is $\omega=\sqrt{k/m}$. This means that the period of oscillation (in other words, the length of time it takes for the mass to return to a particular position) is $2\pi/\omega$. This intuitively makes sense. If $k$ is very large (meaning that the spring is very rigid), then the period of oscillation should be very short, and so $\omega$ is large. If $k$ is very small (meaning that the spring is super flexible), then $\omega$ is small. If $k$ is zero (meaning that there is no spring), then $\omega=0$, and so this agrees with our intuition that there are no oscillations because there is no restorative force present.

Initial Conditions

We’ve determined the general form of the solution $x(t)$, but we still have yet to determine what $A$ and $B$ are. To determine the value of these coefficients, we need to use the initial conditions. These are the displacement and velocity of the block at some particular time point, which is typically at $t=0$ (although not always the case). Let’s take a look at two example cases.

The first is if we use our hands to pull the block out to some initial displacement $x=x_0$, and then simply let it go with zero initial velocity at time $t=0$. We can plug these initial conditions into the general form for $x(t)$. Firstly,

\[x(t=0)=x_0=A\sin(0)+B\cos(0)=B\]This tells us that $B=x_0$. For the velocity, we have

\[v(t=0)=0=A\omega\cos(0)-x_0\omega\sin(0)=A\]This means that $A=0$, and so in this case, our solution function is $x(t)=x_0\cos(\omega t)$. We need a system of two equations in order to solve for the two variables.

Let’s look at another case, where we mass is sitting at $x=0$, and at $t=0$, we give the block an impulse push such that it starts moving with velocity $v=v_0$. We’ll repeat the same process:

\[x(t=0)=0=A\sin(0)+B\cos(0)=B\]This means that $B=0$. For the velocity, we have

\[v(t=0)=v_0=A\omega\cos(0)=A\omega\longrightarrow A=\frac{v_0}{\omega}\]Therefore, the solution function is $x(t)=\frac{v_0}{\omega}\sin(\omega t)$.

These are only two of the many possible cases, but the idea always remains the same. So long as the you have a system of two initial condition equations, you are guaranteed to be able to solve for $A$ and $B$.

Complex Exponentials

Let’s return to the generalized differential equation for simple harmonic motion that we found above:

\[\frac{d^2x}{dt^2}=-\omega^2 x(t)\]We solved this equation by plugging an Ansatz that consisted of a sum a sine and a cosine function. However, this is not the only Ansatz available. Whenever we are solving a homogeneous, constant-coefficient ODE (such as the one above), a good Ansatz to make is always of the form $x(t)=\tilde{A}e^{rt}+\tilde{B}e^{-rt}$ for some set of constant parameters $\tilde{A}, \tilde{B}, r$. Let’s take the first time derivative of this Ansatz:

\[\frac{dx}{dt}=\tilde{A}re^{rt}-\tilde{B}re^{-rt}\]Differentiating once more gives

\[\frac{d^2x}{dt^2}=\tilde{A}r^2e^{rt}+\tilde{B}r^2e^{-rt}=r^2\left(\tilde{A}e^{rt}+\tilde{B}e^{-rt}\right)=r^2x(t)\]If we compare this result with the generalized SHO differential equation from above, then we can conclude that this Ansatz is a solution so long as $r^2=-\omega^2$. In other words, $r=i\omega$, and so

\[x(t)=\tilde{A}e^{i\omega t}+\tilde{B}e^{-i\omega t}\]This solution is called the complex exponential solution, simply because it consists of the sum of complex exponentials. Now, you may be looking at this and scratching your head a bit. Didn’t we just prove that the solution was the sum of sines and cosines? How are we getting two apparently different solutions from the same differential equation?

The “trick” is that the two forms of the solution can be interconverted between each other using the fact that $e^{i\omega t}=\cos \omega t+i\sin\omega t$ from Euler’s formula. Plugging this into our complex solution from above gives

\[x(t)=\tilde{A}\left(\cos \omega t+i\sin\omega t\right)+\tilde{B}\left(\cos \omega t-i\sin\omega t\right)\]Simplifying the right hand side gives

\[x(t)=(\tilde{A}+\tilde{B})\cos\omega t+i(\tilde{A}-\tilde{B})\sin\omega t\]Comparing the coefficients of each of these terms, we can solve for $\tilde{A}, \tilde{B}$ uniquely in terms of $A$, $B$, so in fact, both forms of these solutions are one and the same.

Another “issue” is that this complex exponential solution is more complicated, since we might have complex coefficients and complex exponentials are more difficult to conceptualize physically. Why did we go through the trouble of trying to solve the same problem using this more complicated method? The issue is that although sines and cosines worked for this specific problem, they will not work in the general simple harmonic oscillator problem. For example, in future problems, we will see that there can be friction terms equal to $-\gamma \frac{dx}{dt}$ for some constant parameter $\gamma$. In this case we know by Newton’s second law that

\[m\frac{d^2x}{dt^2}=-\gamma\frac{dx}{dt}-kx\]Because the first derivative of sine and cosine functions are not proportional to themselves, an Ansatz involving sines and cosines will not work! In cases like these, we are forced to use complex exponentials. Don’t worry if this doesn’t make too much sense right now. We will dive deeper into this idea in our discussion on damped oscillations.

Recap

To recap, the solution to the SHO equation $\frac{d^2x}{dt^2}+\frac{k}{m}x=a+\frac{k}{m}x=0$ is

$$x(t)=A\sin(\omega t)+B\cos(\omega t)$$

$$v(t)=A\omega \cos(\omega t)-B\omega \sin(\omega t)$$

$$a(t)=-A\omega^2 \sin(\omega t)-B\omega^2\cos(\omega t)$$

where $\omega=\sqrt{\frac{k}{m}}$.

Exercises

Problem 1

Consider the case from above where a mass is attached to a spring with Hooke’s constant $k$ on a frictionless plane from above. From above, we found that the displacement $x(t)$ is given by

\[x(t)=A\sin(\omega t)+B\cos(\omega t), \quad \text{where }\omega=\sqrt{\frac{k}{m}}\]Assume that at time $t=\pi/\omega$, we know that the displacement $x(t)=x_0$ and the velocity $v(t)=\frac{dx}{dt}=v_0$. Solve for the coefficients $A$, $B$ in terms of these parameters.

Problem 2

This problem is adapted from Caltech’s Ph12a course.

A massless spring with no mass attached to it hangs from the ceiling. Its length is 20 cm. A mass $M$ is now hung on the lower end of the spring. Support the mass with your hand so that the spring remains relaxed, then suddenly remove your supporting hand. The mass and spring oscillate. The lowest position of the mass during the oscillation is 10 cm below the place it was resting when you supported it.

- What is the frequency of oscillation?

- What is the velocity when the mass is 5 cm below its original resting place?

A second mass of $300$ g is added to the first mass, making a total of $M+300$ g. When this system oscillates, it has half the frequency of the system with mass $M$ alone.

- What is M?

- Where is the new equilibrium position?