Pendulums

A pendulum are simply a weight suspended from a pivot using a string so that the weight can swing freely. You might have seen examples of pendulums before in older clocks such as a grandfather clock, which uses the motion of a pendulum to keep track of time. We’ll investigate how this might work later.

A Typical Setup

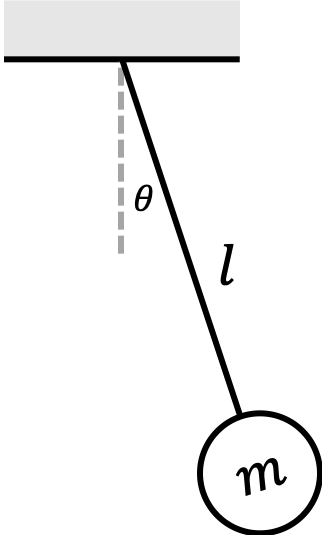

A typical setup for a pendulum system might look something like this:

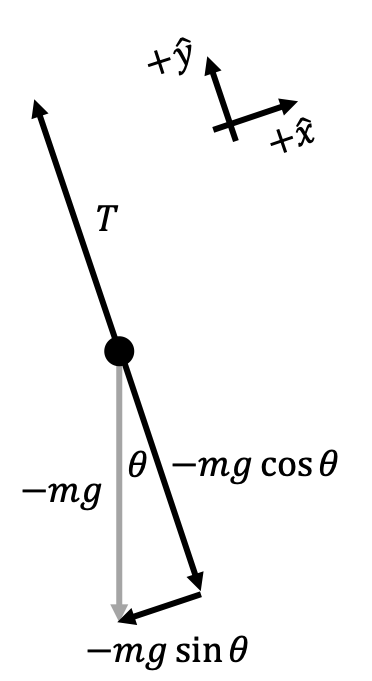

We have a mass $m$ attached to a massless string of length $\ell$. Intuitively, we might imagine the mass to oscillate back and forth so that the angle $\theta$ is oscillating over time. Our goal is to describe how the system evolves over time. Once again, we resort to our typical technique of first drawing a force diagram to illustrate all of the different forces at work. For the mass $m$, we have both the force of tension $T$ from the rope, and also the force of gravity.

Notice that similar to our work with inclined planes, it will be advantageous to work in a slanted coordinate system where the $\hat{y}$ axis aligns parallel to the rope. Because we don’t expect the mass to suddenly start “jumping around”, we can imagine that $T=mg\cos\theta$ so that there is no net force in the $y$ direction. However, with regards to the $x$ direction, we have a net force that looks like it’s a restorative force (given the negative sign and the fact that it is proportional to $\sin\theta$), so let’s analyze this part of the setup. In the $x$ direction, Newton’s second law tells us that

\[ma_x=m\frac{d^2x}{dt^2}=-mg\sin \theta\longrightarrow \frac{d^2x}{dt^2}+g\sin\theta=0\]It’s difficult to do anything here without making any approximations. Let’s assume that the maximum angle of oscillation is very small, which is true for many pendulums. We can conclude in the small-angle approximation that $\sin\theta\approx x / \ell$, meaning that $x\approx \ell \sin\theta$. If we look at the Taylor series approximation for $\sin \theta$, then we can also conclude that $\sin\theta\approx \theta$ and $x\approx \ell\theta$. Plugging these approximations into the equation above, we find

\[\ell\frac{d^2\theta}{dt^2}+g\theta\approx 0 \longrightarrow \frac{d^2\theta}{dt^2}+\frac{g}{\ell}\theta\approx 0\]If we refer back to our work on simple harmonic oscillators, we can see that this equation is exactly equal to the SHODE, and so in with the small-angle approximation, we can describe a pendulum as a simple harmonic oscillator! This means that the solution roughly looks something like

\[\theta(t)=A\sin(\omega t)+B\cos(\omega t), \quad \omega=\sqrt{\frac{g}{\ell}}\]where the constants $A, B$ are fixed by the initial conditions. Although pendulums look very different from the mass-on-a-spring setup that we looked at previously, the mathematics are essentially identical.

Breakdown of Small-Angle Approximation

What happens when the small-angle approximation is no longer true? You can show that the differential equation without any approximations made is given by

\[\frac{d^2\theta}{dt^2}+\frac{g}{\ell}\sin\theta=0\]While this equation looks ostensibly simple, it is essentially impossible to solve by hand. This is why making the small-angle approximation is crucial in pendulum systems.

Friction of Pendulums

After our whole discussion about damped harmonic oscillations, we might want to ask ourselves what damped pendulums look like, and how we can incorporate the idea of friction into our pendulum model. After all, pendulums eventually stop swinging because no physical system is perfect. In reality, there can be energy being dissipated from the friction between the rope and the hinge at the top of the pendulum. However, in most applications this is negligible, and this would be fairly difficult to model in the first place. Therefore, we typically don’t care or factor in an friction into pendulum models.

Back to Grandfather Clocks

Let’s go back to the grandfather clock application for pendulums in keeping time. Let’s say that every time interval between when the pendulum passes through the center of the clock (i.e. every time $\theta=0$) should be one second long. Therefore, the period length should be $T=2$ seconds. Because $T=2\pi/\omega$, and because we concluded from above that $\omega=\sqrt{g/\ell}$ from above, we know that

\[2\pi\sqrt{\frac{\ell}{g}}=2\text{ sec}\longrightarrow \ell= \frac{g\text{ sec}^2}{\pi^2}\approx 1\text{ meter}\]If you look up the length of a typical pendulum in a grandfather’s clock here, it is indeed about 1 meter long! You can also visit a thrift store and confirm this for yourself. Through basic physics principles, we can predict the length of a pendulum clock!

Double Pendulums

A double pendulum is a pendulum with another pendulum attached to its end. This type of system is certainly outside the scope of our discussions, but its interesting to see how this system works. The Wikipedia link here features chaotic, seemingly random trajectories of the two masses, and it is interesting to study how this system works. However, it requires mathematical tools that are too advanced for AP Physics, and so we’ll leave that for a later time.

Exercises

Problem 1

This problem is adapted from Serway Physics, 9th edition.

A man enters a tall tower, needing to know its height. He notes that a long pendulum extends from the ceiling almost to the floor and that its period is 15.5 sec.

- How tall is the tower?

- If this pendulum is taken to the moon, where the free-fall acceleration is $g=1.67 \text{m}\cdot\text{sec}^{-2}$ instead of $g=10\text{m}\cdot\text{sec}^{-2}$, what is the period there?

Problem 2

This problem is adapted from Serway Physics, 9th edition.

A “seconds” pendulum is one that moves through its equilibrium position once each second, meaning the period of the pendulum is $T=2.000 \text{ sec}$. We analyzed this type of pendulum above in our discussion on Grandfather clocks. The length of a seconds pendulums is 0.9927 meters at Tokyo, Japan and 0.9942 meters at Cambridge, England. What is the ratio of the free-fall accelerations at these two locations?

Problem 3

This problem is adapted from Serway Physics, 9th edition.

A simple pendulum is $\ell=5.00$ meters long.

- What is the period $T=\frac{2\pi}{\omega}$ of simple harmonic motion for this pendulum if it is located if it is located in an elevator accelerating upward at $5.00\text{m}\cdot\text{sec}^{-2}$?

- What is its period if the elevator is accelerating downward at $5.00\text{m}\cdot\text{sec}^{-2}$?

- What is the period of simple harmonic motion for the pendulum if it is placed in a truck that is accelerating horizontally at $5.00\text{m}\cdot\text{sec}^{-2}$?